In recent years, designs for children by modern masters like Bruno Munari, Charles and Ray Eames and Alexander Girard have been brought forward, their diminutive audience seen not as undermining but attractive. We should add Fredun Shapur to that pantheon of designers of winning and sculptural objects for children. Shapur’s work was produced by an international array of manufacturers, including Naef, Trendon, Galt Toys, Fischerform and Selecta, but he is best known for transforming Creative Playthings’ logo, packaging and products.

As historian Amy F. Ogata writes in the new book Fredun Shapur: Playing With Design (edited by daughter Mira Shapur), “Shapur produced toys that highlighted and challenged the child’s agency while appealing to the parents’ tastes.” This is a point Ogata made, in greater detail, in her 2013 book Designing the Creative Child: Playthings and Places in Midcentury America, reviewed here.

The slideshow above shows ten spreads from the book, a thorough catalog of Shapur’s work for children. That is still the essential trick performed by the best toys, and the idea that many present-day, Whole-Foods toy companies are predicated on. As I’ve written before, too often it is the latter that comes before the former, with too much emphasis on sustainable materials (or cute typefaces) over the amount of tactile and visual information children are capable of dealing with.

Shapur, who is still alive, and still designing, was born in 1929 in South Africa. His career demonstrates the true internationalism of modernism at mid-century, as he practiced in London, collaborated in Princeton, and was manufactured in Switzerland. Shapur first enrolled at St. Martin’s in London, and then studied graphic design at the Royal College of Art. There, he was taught by Edward Bawden and Abram Games; Games’s work included the logo for the Festival of Britain (1951). Shapur worked in Prague in 1957, where he admired the growing array of Czech modernist toys.

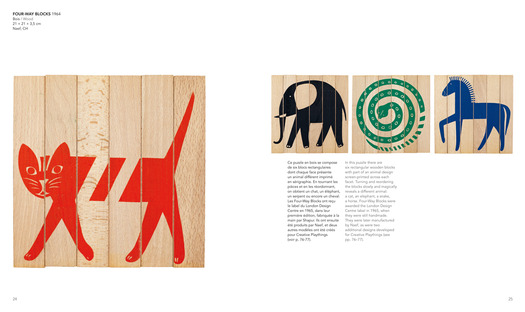

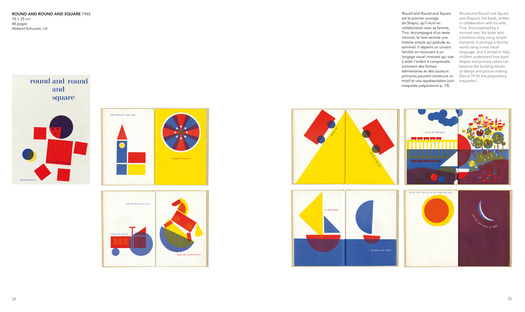

Shapur opened his own office in 1959, working on logos, packaging and posters. He was inspired to create toys by his own children. In 1963, he designed Animal Puzzle, based on a set of interlocking squares, and Four-Way Blocks, using square rods and silk-screened graphics to allow children to make their own staccato creatures. His children’s book, Round and Round and Square (1965), employed a similar reduced geometric vocabulary. In other books he made shapes and colors into characters Blackie the cat and Spot the dog.

Shapur’s first toys were handmade, sanded by himself and his wife. He hired artisans to increase production, and ultimately sought out Swiss manufacturer Naef to increase scale. In the book, Ogata contrasts this way of making to the thousands of new plastic toys entering the postwar market. The few companies that maintained an emphasis on craftsmanship and natural materials are still collectible, like Danish designer Kay Bojesen’s jointed animals.

Shapur’s longest collaborative relationship was with Stephen A. Miller, director of product development for Creative Playthings in the mid-1960s. Miller was hired as part of the expansion of that company after it was bought by CBS in 1966. Shapur first proposed a new logo. “Neither explicitly boy nor girl, nor a child of any specific age, the logo signaled the wide range of products and the sophisticated, mostly un-gendered toys Creative Playthings championed in this period,” Ogata writes. Subsequently, Shapur redesigned the company catalogs and packaging along similar lines. Among my highlights of products designed by Shapur and sold through Creative Playthings are a series of cloth books made by Dean’s, issued in 1971. Animals shows parent and child of a variety of species, Pictures shows helicopters and skyscrapers, a chuch and an interior with Thonet chair.

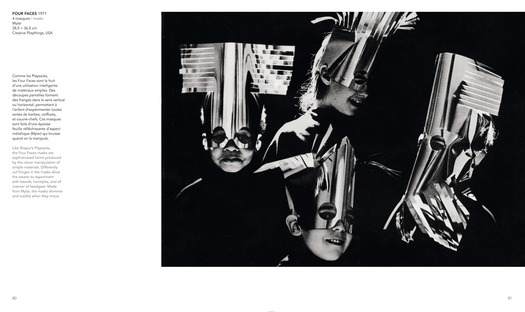

Also clever with materials: his See Through Puzzles (1972) for ages 4+. These were made of printed, clear plastic sheets, which could be layered and rotated to create a complete image. The Four Faces Mylar masks (1971), made of pleated and fringed plastic. 1971 are very David Bowie. And unisex.

Perhaps my favorite Shapur toy, seen in the Museum of Modern Art’s “Century of the Child” exhibition, are the Playsacks made by Trendon (1968). Shapur took a paper sack used for kitchen waste, and transformed it into 12 animal disguises. Necessity is the mother of a father’s invention.

Perhaps my favorite Shapur toy, seen in the Museum of Modern Art’s “Century of the Child” exhibition, are the Playsacks made by Trendon (1968). Shapur took a paper sack used for kitchen waste, and transformed it into 12 animal disguises. Necessity is the mother of a father’s invention. Shapur left Creative Playthings, where he was an official consultant, in 1974, after Miller departed. He designed logo for Miller’s new company, Novo Toys and continued to design toys for variety of European companies until 1980. After his retirement, he began working with discarded objects, leather and paper. The book includes examples mask-like faces made from sardine tins. It’s nice to see the creative mind continuing to play. Playing With Design has thoughtful text and bright, clear photography. The toys look so good, I couldn’t help wishing it also served as a revived Creative Playthings catalog. Anyone?