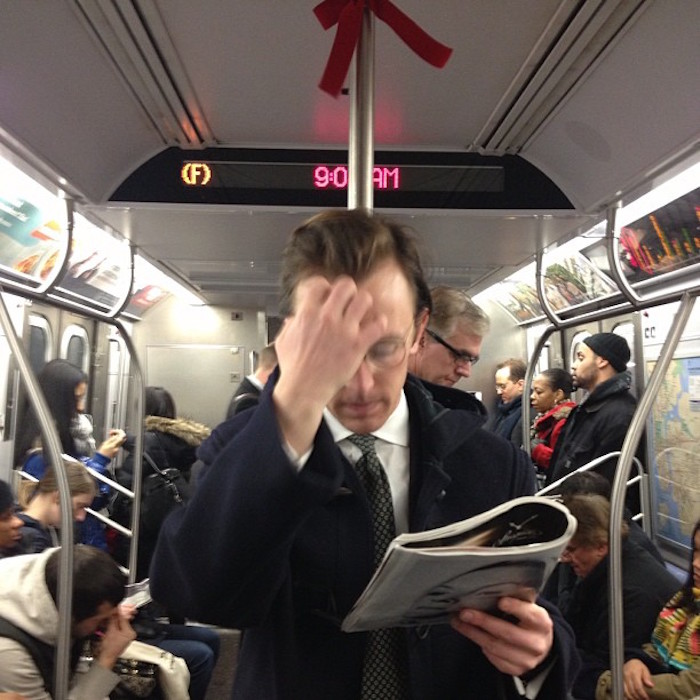

Four years ago, on my way to work, two men were sitting before me as the Q train crossed the Manhattan Bridge. The one on the left wore a suit and was reading a Hebrew book. The guy on the right, in a leather jacket, looked at an Arabic text on the screen of his iPhone. With my iPhone, I took a picture—the first candid photograph I took on the subway—and posted it to Instagram.

There is an additional element in that picture that I didn’t give much thought to at the time: a stainless steel pole. In this image, the pole, which I was holding on to while sneaking the picture (or maybe not; at that point my iPhone camera technique might still have required two hands), conspires with the sides of the frame to isolate these two men from the rest of the crowd, and also, perhaps, from each other. The pole itself suggests a narrative.

The legendary MoMA curator John Szarkowski called his survey of American photography of the sixties and seventies Mirrors and Windows. Street photography dominated the show; those were the glory days of William Eggleston, Lee Friedlander, Stephen Shore, and Garry Winogrand. For Szarkowski, mirrors and windows are not mutually exclusive. They describe a “continuous axis” along which the artist-photographer had to find the right balance between looking outward and looking inward, between “a personally satisfactory resolution of the contesting claims of recalcitrant facts and the will to form.”

A show of American subway photography—a strand of street work—could be called Poles. (Bruce Davidson was in Mirrors and Windows, which opened at MoMA in 1978; his Subway did not come out until 1986.) The subway pole is a parallel axis to the one from mirror to window. Like the word “cleave,” which sometimes means to separate things and, at other times, to stick them together, the pole can be a refuge for lovers, the bars of a cage, an armature for modeling clothes or showing off tattoos. In the foreground, the pole puts distance between the viewer and fellow travelers, but it can also turn a single frame into a diptych, so an R160 subway car becomes an iconostasis of the modern urban condition.

Most subway riders hold the pole with the entire hand, but look long enough and variant behaviors will crop up: three-fingered, like a sloth; one-fingered, which is more gesture than effective grip; with a tissue, to establish a cordon sanitaire during flu season. On an empty car, a tall person will occasionally prop his up foot on the pole as if traveling with his own vertical ottoman, joining the ranks of leaners, dancers, and others who occupy more than their unwritten allotment of public space.

There is an additional element in that picture that I didn’t give much thought to at the time: a stainless steel pole. In this image, the pole, which I was holding on to while sneaking the picture (or maybe not; at that point my iPhone camera technique might still have required two hands), conspires with the sides of the frame to isolate these two men from the rest of the crowd, and also, perhaps, from each other. The pole itself suggests a narrative.

The legendary MoMA curator John Szarkowski called his survey of American photography of the sixties and seventies Mirrors and Windows. Street photography dominated the show; those were the glory days of William Eggleston, Lee Friedlander, Stephen Shore, and Garry Winogrand. For Szarkowski, mirrors and windows are not mutually exclusive. They describe a “continuous axis” along which the artist-photographer had to find the right balance between looking outward and looking inward, between “a personally satisfactory resolution of the contesting claims of recalcitrant facts and the will to form.”

A show of American subway photography—a strand of street work—could be called Poles. (Bruce Davidson was in Mirrors and Windows, which opened at MoMA in 1978; his Subway did not come out until 1986.) The subway pole is a parallel axis to the one from mirror to window. Like the word “cleave,” which sometimes means to separate things and, at other times, to stick them together, the pole can be a refuge for lovers, the bars of a cage, an armature for modeling clothes or showing off tattoos. In the foreground, the pole puts distance between the viewer and fellow travelers, but it can also turn a single frame into a diptych, so an R160 subway car becomes an iconostasis of the modern urban condition.

Most subway riders hold the pole with the entire hand, but look long enough and variant behaviors will crop up: three-fingered, like a sloth; one-fingered, which is more gesture than effective grip; with a tissue, to establish a cordon sanitaire during flu season. On an empty car, a tall person will occasionally prop his up foot on the pole as if traveling with his own vertical ottoman, joining the ranks of leaners, dancers, and others who occupy more than their unwritten allotment of public space.

The pole can bring strangers together, and not just in a photograph. Subway riders can feel the body heat from the hand of a passenger who recently let go of that pole. Most passengers, upon feeling that warmth, will slide over a few inches to a cold and uninhabited section of stainless steel, restoring the illusion of being alone in the crowd. The pole, welded in place and sturdy, is a transitional object. It sustains the belief that you are independent, even as you depend on a fragile public authority to get you where you want to go.

++++

See more of Blake Eskin's subway photography in the new issue of Observer Quarterly, available here.