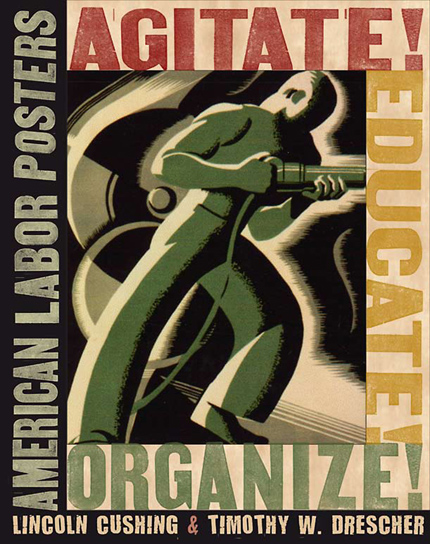

Agitate! Educate! Organize!: American Labor Posters (Cornell University Press, 2009)

Labor Day in North America started with typography. In 1872, printers in the Toronto Typographical Union rose up to demand a nine-hour workday and Saturdays off. When protesters were arrested and their demands went unmet, they called a strike. Others joined, and the demonstrations quickly grew to become the largest in Canada to date. That pressure, along with nudging from anxious business owners, ultimately pushed politicians to pass Canada’s Trade Union Act, which legalized and protected union activity. The victory gave rise to an annual celebration, Labor Day—which in turn inspired U.S. workers. In 1894, striking railroad employees and their supporters pushed Congress and President Grover Cleveland to pass a law creating a national Labor Day.

Workers have had their share of victories and defeats in the hundred years since, and today a mere 12 percent of the American workforce is unionized. Throughout this history, graphic design has played an important supporting role: bringing workers together, calling for action, celebrating victories and commemorating fallen heroes.

Surprisingly, a survey of this visual landscape has never before been published. Agitate! Educate! Organize!: American Labor Posters (Cornell University Press) is the first of its kind. Compiled and edited by Lincoln Cushing and Timothy W. Drescher, the book spans the history of the labor movement in the U.S. Its 216 pages are packed with 268 color reproductions, many of them full-page. The accompanying text provides interpretation and context. (The book is union printed, of course.)

PLAY SLIDESHOW

The images trace stories of work in America through a wide variety of visual strategies. Many of the issues are as relevant as ever: fighting for safe working conditions, dignity and respect, a fair wage and an end to discrimination.

I spoke with Lincoln Cushing about the book, its genesis and the trouble with political posters.

John Emerson

What are the origins of the project?

Lincoln Cushing

Around 2001, I was hired as a librarian at the Institute of Industrial Relations at UC Berkeley. Being a librarian is my second career. I had been a printer for 20 years and was familiar with the labor movement. Once in that job, I realized that an area of material that hasn’t been well documented was poster art. I applied for and received a grant to identify repositories of posters around the country. The grant paid for travel and research. After poking around, I found a publisher interested in doing a book and it took off from there. I picked up a co-author, Tim Drescher, who is a mural scholar and a good friend of mine.

Emerson

Now all of this is in a database?

Cushing

Yeah, the database has about 900 images of material that I’ve shot.

Emerson

Will you make it accessible on the web?

Cushing

Sometimes archives are a little skittish about the web. I’m negotiating with them at a series of levels. If everybody agrees to let me at least put up catalog information and a thumbnail, or if they say, “Okay, put up a medium-resolution image‚” I’ll do that.

Emerson

What was the state of the graphics you found?

Cushing

Posters are at the fringes of what most institutions are capable of handling and cataloging. It’s rare to see proper catalog records for these works, much less a digital object. They are awkward to store, and digitization using conventional means is a high barrier. The way I do it is with a single-lens-reflex camera and strobe lights. I can shoot pretty efficiently and get high-resolution files. When we went back to those archives, I took my camera and I would set up my rig in a closet or whatever room was available and shoot the materials on site. All of the images in the book are ones I shot. When I shoot the posters, I give the archives high-res files they can use for their own catalogs.

Emerson

What surprised you about doing the book?

Cushing

I’ve done labor posters and I thought I knew what I would run across. But I kept seeing particular styles and subjects that were just mind-blowing. Like the range of social issues under the “workers” umbrella — because it’s not just about unions. Take posters about occupational safety and health. There’s a focus where we think, “Ew, how do you design an effective poster about people losing their fingers?” Well, there're some pretty good ones in there and it’s a pretty important subject. But if you grabbed a designer out of school and said, “Would you like to design a poster about occupational safety and health?” they’d look at you like you were crazy.

Emerson

It was interesting to see the wide variety of visual strategies: from photo montage to simple cartoons, from the monumental figures of the WPA images to the florid and psychedelic lettering of 1960s posters. Some images were clearly designed to be posted in a workplace, some were designed to be held up on a picket line. And there were a couple of early offset images that were very elaborate and luxuriously illustrated and printed. I wanted to know more about these.

Cushing

That elaborateness was typical of posters from that period. You could do a dissertation just on all the objects in those posters: What’s the poster in this poster?

As for the stylistic range, many of these were not designed by professional graphic artists. They were done by volunteers who would help out for the cause. Or they were early projects of people who might have had some training. Occasionally, you’d clearly have something done by a professional design firm, but it really does run the gamut. It’s fun to compare them and see which are effective and which less effective. We tried to pick the strongest ones in terms of both historical developments and design. But many are sort of outsider art and it gives a fresh perspective on design approaches.

Emerson

As a poster-maker, did you find some that were more effective to you, say, using humor or outrage or visual metaphors?

Cushing

One measure of a powerful image is whether it gets recycled. So we showed the example of “We Can Do It.” As far as I can tell, it’s the most imitated and reproduced image of the labor movement. I’ve got dozens and dozens of examples that I’ve just touched on in this book.

The evaluation of how effective a poster is would really require after-the-fact interviews and focus groups. Most of it is conjecture. But you can always look at an image and say, “Huh, it works for me.”

Emerson

I’ve seen many beautiful political posters recently, but they seem more like fine art: printed with multiple screens by hand on quality paper. Do political posters have the same function today as in the past?

Cushing

The people I know who design political posters these days generally do a bifurcated print run. They’ll produce part of their edition in one color on cheap paper to be wheat-pasted and spread around for free, and they’ll do another version in a limited edition to raise money. The Mexicans in the ’40s used that same model.

There’s a range of posters that depend on their intended audience and use. When you walk down a busy street, you see a huge number of ads pasted everywhere, but also political stuff. Then, there’s a way the political stuff gets posted in safer, more protected spots — such as inside a coffee house or union hall — where it’s not competing quite the same as out on the street.

Emerson

I appreciated that your research was very open, where you published not just the bibliography but also the contact information of the archives. Anyone can pick up this research and take it somewhere else.

Cushing

There’s clearly so much to do in the field that I’m trying not to be proprietary. I would love it if some grad student said, “Wow, I want to jump on this. What can I do?” And the fact that there has never been a book like this in this country is remarkable to me.

Emerson

Do you think it speaks to the current state of organized labor?

Cushing

Well, it’s partly labor and partly that posters in general are a marginalized medium — except for certain kinds: World War II posters, rock posters. Political posters are really at the fringes of serious scholarship.

Emerson

Are you now or have you ever been a member of a labor union?

Cushing

I was a member of the Graphic Communications International Union for almost 20 years. Then when I was a librarian, I was a member of the American Federation of Teachers.

Emerson

So you have deep experience with union culture.

Cushing

Yeah, it’s glorious and horrible at the same time and it’s one of those things where you think it’s crazy, yet the alternative of not having it would be even worse.

One reason my co-author and I really wanted to do this book is that it represents the best of the labor movement: the idea of people speaking up for themselves, looking out for their rights, being proud of their occupation and their trades. Whether you agree with unions or not, this shows you why unions exist and the best of what they can be.

Emerson

You’ve done a few books on posters before: Cuban posters, Chinese propaganda posters, Latin American posters. There seems to be a thread running through your research. Do you have an overarching goal or are these scattered interests?

Cushing

Partially it’s because I started designing posters in 1969. I was a high school student in Washington, D.C., in the ’60s and the woman who inspired me was Sister Mary Corita.

My mission in life is to lend some respect to scholarship around political poster art — that it’s not just a goofy, marginalized, misunderstood genre, but has a lot of parts that merit respect and recognition.

My next book is about the unique role of the San Francisco Bay area in poster art. This region has been continuously producing independent political posters since 1965 — longer than anywhere else. Many other places have had major moments of poster output. Minneapolis is a smaller city that gave rise to a huge number of posters. Usually it takes a bigger city to have a thriving poster culture. Tiny little towns don’t often do it. But sometimes you have a gifted artist and a community that works together and you have a blossoming.

Emerson

I’ve looked into publishing larger format, full-color books, and found publishers generally don’t want to do it because it’s so expensive. How did you pull it off?

Cushing

We had to subsidize this book. We had to raise $18,000, which actually ended up not being as hard as I thought. The California Labor Federation endorsed the project. They sent a letter out to unions all over the state and raised $8,000. Two local foundations kicked in $5,000. That meant it could be an affordable $25 book instead of a $60 coffee table book.

Emerson

Excellent. That fits nicely with the theme.

Cushing

It really made a difference. I didn’t want an expensive book and I also couldn’t send it off to Hong Kong to be printed. So it turned out to be well worth it.

I should add that Cornell University Press was wonderful and encouraging. I gave their designer carte blanche. We kept throwing them more and more images we thought were useful. Ten years ago, a publisher would have complained and talked about color separations. It’s a whole different ballgame now. The fact that we were prepared at this end and they were flexible at their end, resulted in what I think is a much more powerful book.

Emerson

In the book, you talk about how the posters inspired workers, but they’re also inspirational to artists and designers. What’s a good way for graphic designers to get involved?

Cushing

This is what I tell people when I lecture at art schools: They’ve learned the technique but they haven’t learned how to work with a nonprofit organization. It’s a process that has all sorts of potential pitfalls and it can easily alienate someone if they go into it with a certain mindset.

The short version is, look for something in your community that resonates with what you care about and then talk to those people. You don’t want to say, “Okay, I’ll just design whatever you want me to do.” You’ve got to negotiate a balance between what their expertise is, what your expertise is and what the parameters are going to be around that. The clearer you are about that, the better. And often the only way to do that is trial and error.

But for many people it’s a wonderful way to build a portfolio. A bumper sticker, a T-shirt or a picket sign for an immigrant rights rally — that can be really cool. I encourage people to look around and see how many projects there are for labor organizations as well as labor support organizations — because there are all sorts of groups out there that aren’t unions but deal with workers’ rights or immigrants’ rights. Every community has some group in labor support that would welcome a designer walking in and asking, “Do you need help?”