View from the ramp looking upwards in the Zaha Hadid's newly-opened MAXXI center in Rome

This past weekend marked the grand opening of Rome's MAXXI National Museum of 21st Century Arts, which is being billed as the first national museum dedicated to contemporary creativity and thought as a great campus dedicated to culture, a laboratory of experiment, study and research. The museum itself was designed by the noted Iraqi architect Zaha Hadid, whose design was chosen from more 272 entries, allegedly because of her ability to integrate the space into the existing urban fabric. In Hadid's view, densities are distributed around an open campus, which is navigated on the basis of directional drifts. "This is indicative of the character of the center as a whole," notes the architect, "porous, immersive — a field space."

Which, in essence, she accomplishes quite well. Hadid's plan, at first blush, is housed beneath a facade that sits quietly on an otherwise broad street, but once you turn the corner, it explodes with curvilinear craziness. The public areas flow easily into the opening foyer, where visitors are introduced to a series of spaces of varying and intersecting heights. And here, Hadid succeeds in ways that Daniel Libeskind — in his extension to Gió Ponti's Denver Art Museum — does not: there's a successful counterpoint system in place, with shifting scales guiding visitors through complex collections of interior spaces. Unlike Liebeskind's addition, Hadid's design decisions never seem indulgent to the point of compromising the experience for her public: her loopy lines never overwhelm viewing patterns, but instead, seem to play against and work within them. There's an interplay, too, between public and more private spaces, with subtle lighting in a series of sequenced hallways expertly guiding the traffic flow. Hadid deftly articulates smaller galleries within the Maxxi's larger exhibition spaces with a ramp system that meanders up and down, gesturing ever so loosely to Wright's Guggenheim Museum. Unlike the Guggenheim, however, the Maxxi's 29,000 square meter footprint is a staggering vision in a densely packed city like Rome, but the program is at once dynamic and sensitive, with compelling corners that allow for quiet contemplation within an otherwise mammoth space. The signage is surprisingly good, too: clean, simple, playful and functional.

But in a space that calls attention to itself as the MAXXI center seems destined to do, there are some jarring details. We spotted more than a few examples of shoddy corners and observed, too, examples throughout the center of a kind of strangely illuminated filth.

Paradoxically, too — especially given the fanfare accompanying the opening of the building — the area devoted to Hadid's oeuvre was notably empty when we visited: the press, as it turned out, were much more interested in documenting the starchitect's grande entrance than observing the models and photographs exhibited here as material evidence of this enormous undertaking.

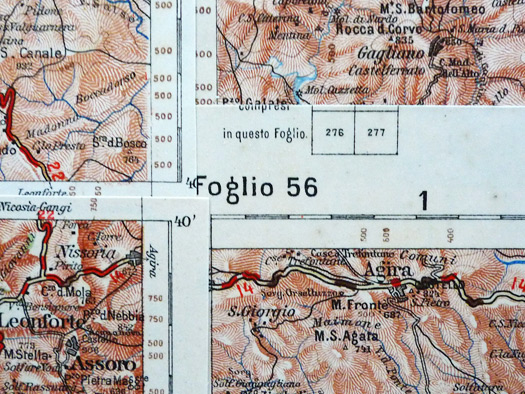

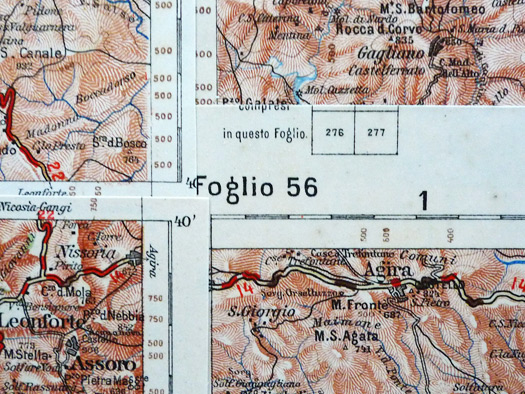

The opening exhibition is broad and international, with multiple highlights: from Yinka Shonibare's Henrik James 1843/1916 and Hendrik C Andersen 1872/1940 (headless mannequins wearing Western clothing made from European-produced but African-inspired batik fabrics); to William Kentridge's theatrical camera obscura which combines digital fireworks with Mozart's The Magic Flute in puppet-theatre scaled sensurround; to Flavio Favelli's oversized map of italy, cut up and reassembled to form the shape of the Peninsula at a scale of 1:250,000.

This past weekend marked the grand opening of Rome's MAXXI National Museum of 21st Century Arts, which is being billed as the first national museum dedicated to contemporary creativity and thought as a great campus dedicated to culture, a laboratory of experiment, study and research. The museum itself was designed by the noted Iraqi architect Zaha Hadid, whose design was chosen from more 272 entries, allegedly because of her ability to integrate the space into the existing urban fabric. In Hadid's view, densities are distributed around an open campus, which is navigated on the basis of directional drifts. "This is indicative of the character of the center as a whole," notes the architect, "porous, immersive — a field space."

Which, in essence, she accomplishes quite well. Hadid's plan, at first blush, is housed beneath a facade that sits quietly on an otherwise broad street, but once you turn the corner, it explodes with curvilinear craziness. The public areas flow easily into the opening foyer, where visitors are introduced to a series of spaces of varying and intersecting heights. And here, Hadid succeeds in ways that Daniel Libeskind — in his extension to Gió Ponti's Denver Art Museum — does not: there's a successful counterpoint system in place, with shifting scales guiding visitors through complex collections of interior spaces. Unlike Liebeskind's addition, Hadid's design decisions never seem indulgent to the point of compromising the experience for her public: her loopy lines never overwhelm viewing patterns, but instead, seem to play against and work within them. There's an interplay, too, between public and more private spaces, with subtle lighting in a series of sequenced hallways expertly guiding the traffic flow. Hadid deftly articulates smaller galleries within the Maxxi's larger exhibition spaces with a ramp system that meanders up and down, gesturing ever so loosely to Wright's Guggenheim Museum. Unlike the Guggenheim, however, the Maxxi's 29,000 square meter footprint is a staggering vision in a densely packed city like Rome, but the program is at once dynamic and sensitive, with compelling corners that allow for quiet contemplation within an otherwise mammoth space. The signage is surprisingly good, too: clean, simple, playful and functional.

But in a space that calls attention to itself as the MAXXI center seems destined to do, there are some jarring details. We spotted more than a few examples of shoddy corners and observed, too, examples throughout the center of a kind of strangely illuminated filth.

Paradoxically, too — especially given the fanfare accompanying the opening of the building — the area devoted to Hadid's oeuvre was notably empty when we visited: the press, as it turned out, were much more interested in documenting the starchitect's grande entrance than observing the models and photographs exhibited here as material evidence of this enormous undertaking.

The opening exhibition is broad and international, with multiple highlights: from Yinka Shonibare's Henrik James 1843/1916 and Hendrik C Andersen 1872/1940 (headless mannequins wearing Western clothing made from European-produced but African-inspired batik fabrics); to William Kentridge's theatrical camera obscura which combines digital fireworks with Mozart's The Magic Flute in puppet-theatre scaled sensurround; to Flavio Favelli's oversized map of italy, cut up and reassembled to form the shape of the Peninsula at a scale of 1:250,000.

Yinka Shonibare, Henrik James 1843/1916 and Hendrik C Andersen 1872/1940, 2001

William Kentridge, Preparing the Flute, 2004-2005

William Kentridge, Preparing the Flute, 2004-2005, detail

Flavio Favelli, Carta d'Italia Unita, 2010

Flavio Favelli, Carta d'Italia Unita, 2010, detail

It is difficult to express the degree to which any new building registers as odd in central Rome: this is, after all, a city which prides itself on its visible ancient culture, from acqueducts to ruins, stone statuary to signature paint colors. (Richard Meier's marble contruction for the Ara Pacis [Alter of Peace] — which is essentially a glass envelope surrounding an altar dating to the first century B.C. — was greeted with shock when it debuted in 2006.) In what may be viewed as a targeted attempt to controlled its own PR, Hadid's contribution to the city appears aimed to deflect potential critics by focusing not so much on the city's visual identity as its cultural vitality. "The MAXXI is like an antenna," notes Maxxi Foundation President, Pio Baldi, "transmitting Italy's contents to the outside world while, in turn, receiving the flux of international culture from the outside." Whether or not such ambitious international exchange begins to take shape here, the building itself does indeed seem to invite a kind of engaged activity, with interlocking walls and overlapping voids and a rather exciting, physical call to interaction. In this view, the notion of a field space seems apt: it's less a museum than a cultural microcosm in which art and architecture — and past and present — dynamically coexist.

It is difficult to express the degree to which any new building registers as odd in central Rome: this is, after all, a city which prides itself on its visible ancient culture, from acqueducts to ruins, stone statuary to signature paint colors. (Richard Meier's marble contruction for the Ara Pacis [Alter of Peace] — which is essentially a glass envelope surrounding an altar dating to the first century B.C. — was greeted with shock when it debuted in 2006.) In what may be viewed as a targeted attempt to controlled its own PR, Hadid's contribution to the city appears aimed to deflect potential critics by focusing not so much on the city's visual identity as its cultural vitality. "The MAXXI is like an antenna," notes Maxxi Foundation President, Pio Baldi, "transmitting Italy's contents to the outside world while, in turn, receiving the flux of international culture from the outside." Whether or not such ambitious international exchange begins to take shape here, the building itself does indeed seem to invite a kind of engaged activity, with interlocking walls and overlapping voids and a rather exciting, physical call to interaction. In this view, the notion of a field space seems apt: it's less a museum than a cultural microcosm in which art and architecture — and past and present — dynamically coexist.