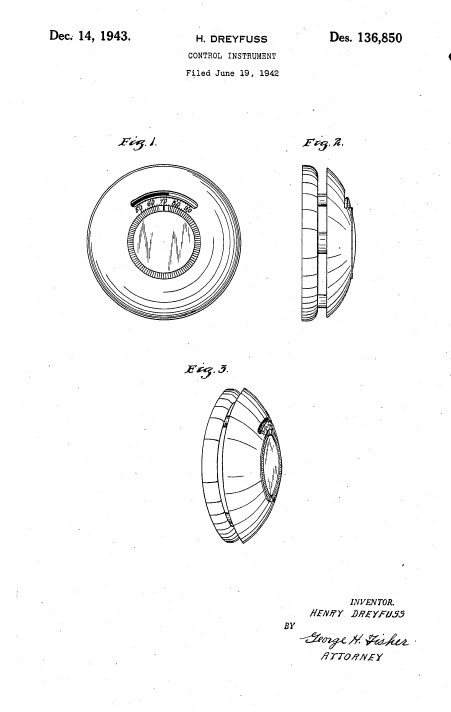

Honeywell Round thermostat, 1953; Nest thermostat, 2011 (via TechCrunch)

Updates this week on two design stories I wrote about last year. I hope a little outrage is healthy.

First, it is not only me that noticed the operational similarities between the Henry Dreyfuss-designed Honeywell Round and the new Nest thermostat. This week, Honeywell sued Nest for patent infringement. Most of the cited patents had to do with new technologies involving the way the thermostat learns your heating and cooling habits, and a "natural language installer" that asks the owner questions rather than having you punch complicated combinations of buttons, but two of them, 7159789 and 7159790, date from the 1930s to the 1950s, when Honeywell's engineers were working with Dreyfuss to make the thermostat more intuitive.

As I wrote in December,

Dreyfuss simplified the selection process, reducing heat control to its essence: one curved thermometer; two arrows, one for desired temperature, one for actual temperature; and one gesture, a hand to the Round's cupped surface, clockwise for hotter, counter-clockwise for cooler. In our Apple-y age, Dreyfuss's efforts seem a precursor for interaction design, which seeks to reduce an action to the simplest graphics and the fewest screen-based moves.Coverage of the lawsuit on tech blogs has predictably focused on the interaction design patents (predictably because these are the same blogs that failed to mention Dreyfuss the first time around). And the general attitude toward Honeywell seems to be: OK, so you had the technology. But what you did with it was crap. The headline on TechCrunch's useful summary: "Honeywell vs Nest: When The Establishment Sues Silicon Valley." On Slate, Farhad Manjoo has a more thorough explication of the anti-Honeywell sentiment.

Honeywell seems to have patented a bunch of great ideas in order to just sit on them. The sad thing is that if it tried, Honeywell seems capable of building a thermostat that’s every bit as wonderful as the Nest. From my testing, I found that Honeywell really does make great home heating and cooling equipment. If it competed in the marketplace rather than in the courts, I suspect it could really turn up the heat on Nest. (Sorry, couldn’t resist.)

Henry Dreyfuss, Honeywell Thermostat Patent D-136,850

But the Round technology, the simplicity of turning a dial to change the temperature, is in many ways the most appealing aspect of the Nest, and the circular shape the element that sets it apart. Honeywell was stupid not to bring it back, but I'm not so sure anyone else has a right to use it. It may be the old patents, rather than the new ones, that help Honeywell make its case.

I must admit, while the tech blogs have a knee-jerk affinity for Apple (and former Apple engineers), I have a knee-jerk affinity for the industrial design greats of old. I couldn't believe that Walter Isaacson, in his biography of Steve Jobs, wrote as if Apple were the first computer company to have a design program. There's no reason to be so snotty about old tricks, and ignorance of the work of Dreyfuss and Eliot Noyes is no excuse.

Manufacturers Hanover Trust (SOM, 1954); Ezra Stoller/ESTO (via Architect's Newspaper)

The second update concerns the fate of Manufacturers Hanover Trust on Fifth Avenue, the bank designed by Gordon Bunshaft, with a vault by Dreyfuss and screen by Harry Bertoia, and the subject of a preservation lawsuit. I wrote about the fear many of us felt when that screen disappeared, under mysterious circumstances, in the fall of 2010. Ada Louise Huxtable, who reviewed the building soon after its opening, wrote in the Wall Street Journal,

It's time to stop worrying about whether New York has enough "starchitecture" and consider the ways in which we are destroying or sabotaging the architecture we already have through neglect, ignorance, disfigurement, willful disregard and the sacrosanct belief that nothing takes precedence over the investment opportunities encouraged by Manhattan's stratospheric real estate values.Well, the screen is going back, as reported on the New York Times ArtsBeat blog, under the headline, "Preservationists Win a Battle Over Former Manufacturers Hanover Trust Building."

A sculptural screen of 800 floating metal panels by the artist Harry Bertoia will be returned to its home at 510 Fifth Avenue as part of a legal settlement that was made public on Wednesday. The settlement is a result of a lawsuit filed by preservationists in July accusing the building’s owner, Vornado Realty Trust — abetted by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission – of disregarding restrictions intended to protect the interior. The settlement also provides that the landmarks commission expand its designation of the interior to include a black granite wall that is part of the former vault space.So Dreyfuss and Bertoia will be preserved, but what of the interior around them? After the interior was landmarked, Vornado went ahead and gutted it, tearing out the side-slung escalators as well as the floor, luminous ceiling, and marble cladding on the columns. When I saw the structure standing bare I thought, Oh no, they are never going to put that back. So the fact that they have to add a little glass and put the sculpture back somewhere (like the private third floor, perhaps?) doesn't even count as a slap on the wrist. The first floor will still be divided in two, and a entrances added on Fifth Avenue. The escalators will run east-west. It will be like every other cheap chic clothing emporium on the block, frontal, stuffed.

By being brazen, Vornado has destroyed the inside and the outside of a landmark building, one of the best in New York of the 1950s. I think that hardly counts as a win. It makes me angry that there are no teeth to our preservation laws and no critics powerful enough to shame.