I decided to write about Gil Elvgren (1914–1980) when I saw that a single painting of his recently sold for $209,000 at Heritage Auctions. I have long been an admirer of his tasteful pinup art and knew his original work was expensive, but this was a record-setting sale. Heritage Auctions has been the primary auction house for his work for years.

In 1933, during the height of the Great Depression, nineteen-year-old Gil Elvgren thought he wanted to be an architect, but that quickly went by the wayside after taking his first drawing classes at the Minneapolis Art Institute. After marrying his high school sweetheart, they moved to Chicago, where he continued his studies with teacher Bill Mosby at the American Academy. Mosby said in an interview years later that “no one worked harder than Gil Elvgren.” He finished three years of work in just two years, painting day and night and even during the summers. By 1940, Elvgren was working with Haddon H. Sundblom (1899–1976), the man who played an important role in his development as an artist. It was Sundblom who mentored the young Elvgren, teaching him the technique for which he is most remembered—his silky brushwork.

In the beginning of his professional career, Elvgren took commissions from several companies, but it was his girly calendars for Brown & Bigelow that eventually made him famous. While other illustrators of the same period took whatever kind of illustration work came their way—Elvgren was single-minded from the get-go about what he wanted to paint. He wanted to paint women—and he did, like few other. Throughout the years he did take other kinds of illustration work, but it was the feminine form that drove his passion.

The late Charles Martignette, one of the foremost collectors of Elvgren’s work, interviewed illustrator Robert G. Harris (1911–2007) who knew Elvgren. Harris remembered how Elvgren was envied by most of his fellow illustrators, especially at the Society of Illustrators in New York. For them, Elvgren had the “dream career.” To their thinking, he painted beautiful women every day of his life, while they had to regularly accept the often-boring tasks required in their commissions. Even straightlaced Norman Rockwell once said he was envious of Elvgren, “because he got to work with beautiful women all day.”

In the 1990s, a renewed interest in pinup model Bettie Page created the right climate for collectors to rediscover Elvgren. The value of his work began to grow, and has skyrocketed in price as of late.

Elvgren’s niche was the approachable girl next door, the flirty girl who was so attractive and confident she didn’t mind if you looked. What he cared most about a girl that that she be cute, with a face capable of expression. If she didn’t already have “the Elvgren look,” (buxom, flirty, with a pouty mouth and arched eyebrow), he would add the features he wanted. One writer described an Elvgren girl as “having legs six inches longer than normal and anatomically plausible.” Elvgren’s youngest son Drake said his dad once told him: “You find me a cute face, I can fix the rest.”

I would be remiss not to name other famous pinup illustrators working at the same time, like Alberto Vargas (1896–1982) who became famous with his work for Playboy, or George Petty (1894–1975), famous for his work for Ridgid Tools calendars. But none had the particular creamy paint quality that Elvgren used—a painting style that was confident and rich. His work was often imitated, but none could quite match his style. The only artist who came close was William (Bill) Medcalf, who was actually a protégé of Elvgren. Medcalf learned his style by working directly with Elvgren at Brown & Bigelow.

Illustrators today will agree that Elvgren sits comfortably in the same esteemed category as Norman Rockwell (1877–1978), James Montgomery Flagg (1877–1960), Charles Dana Gibson (1867–1944), Howard Chandler Christy (1873–1952), J. C. (Joseph Christian) Leyendecker (1874–1951), and further back, even Howard Pyle (1853–1911) of the Brandywine School.

The American Dream that Elvgren was selling was the white American Dream. But to that point, the country was selling it too. Inclusion came about only by protest and social upheaval. The dream was sold by the government, in school textbooks, at the movie theaters and in everywhere in popular culture. Still, today we can look at his work for what it was at the time—selling the “ideal” woman for the enjoyment of men, and women who aspired to live up to it. Elvgren is remembered because few painted the “girl next door” better than he did.

++++

Bear Facts (A Modest Look; Bearback Rider), Brown & Bigelow calendar illustration, 1962. This painting, one of Elvgren’s all-time greatest and most popular; courtesy Heritage Auctions

Bear Facts (A Modest Look; Bearback Rider), detail

Girl on Bicycle, NAPA Auto Parts advertisement, circa 1975

Red Head on the Phone

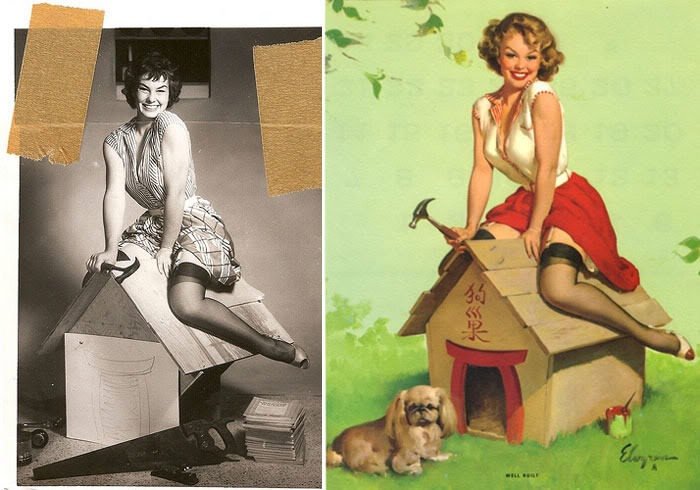

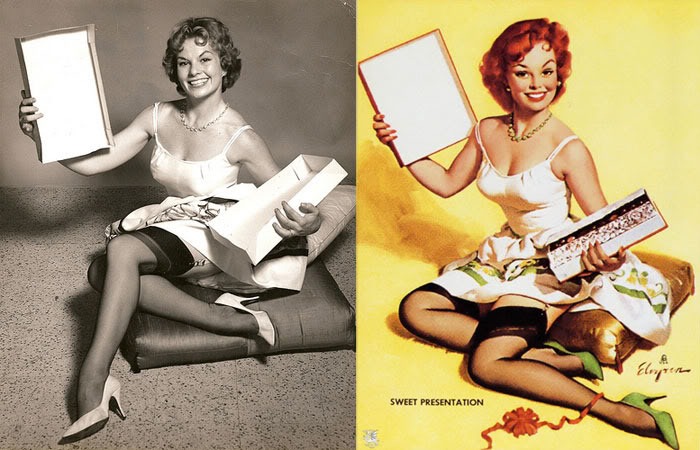

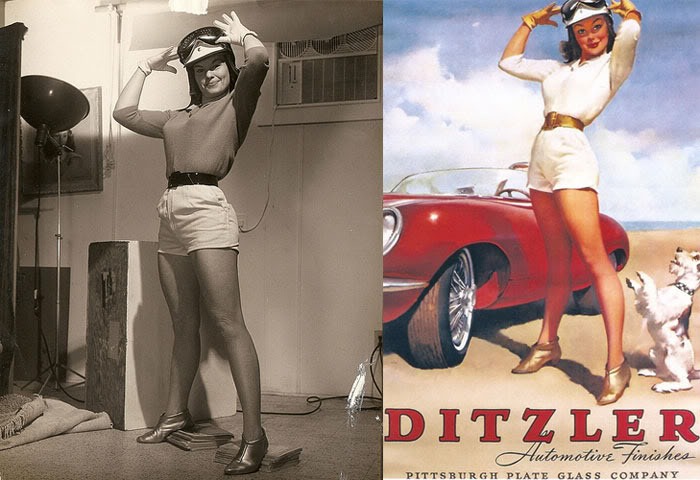

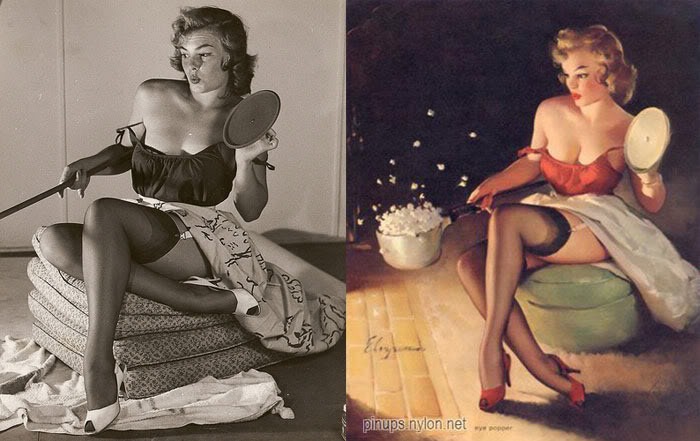

Elvgren took source photographs that served as reference for all his work

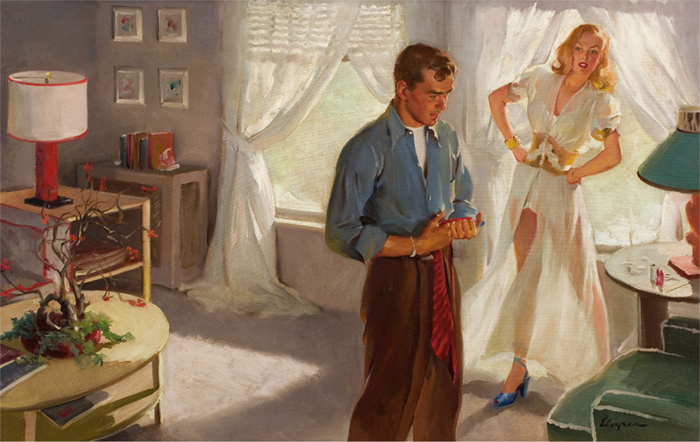

The Three Dollar Bill, Today’s Woman magazine, story illustration, circa 1946

Reference photo and illustration by Gil Elvgren

An Orchid for Miss Sylvania

On the Fence, 1959

Most of Elvgren’s work ended up as calendar art for blue-collar businesses, such as auto repair businesses

Reference photo and final illustration for Ditzler Automotive Finishes

Reference photo and final illustration for popping corn

Elvgren painting for Coca-Cola, c. 1940

++++

All images reproduced here under the Fair Use Act and are copyright © the original owners.