In 1896, the Lumière Brothers screened a black-and-white short film of a train pulling into a station. Parisian moviegoers were so unaccustomed to the filmic medium, the urban legend goes, that they ran out of the theater screaming for their lives, fearing the train might hit them. Today, our contemporary equivalent to the turn of the century’s “shock of the new” might be the unfamiliar medium of virtual reality (VR). Something as simple as a moving train experienced in a virtual world can induce terror and awe.

It’s no wonder that art made for virtual reality platforms is starting to grab eyeballs. In the past six months in New York, you could immerse yourself in experiences developed for the Oculus Rift headset at MoMa’s Björk show, the New Museum’s Triennial, the Tribeca Film Festival’s public Storyscapes exhibition, and the Sensory Stories show at the Museum of the Moving Image, to name just a few recent exhibitions. And if, like me, you’re not a hardcore gamer who already owns your own headset, putting on the clunky black box and headphones until they fit Goldilocks-style—juuust right—on your head, and gasping, as your whole field of vision fills with another vivid world, feels holy every time. Often this awe is blessing, but occasionally with new technologies, it can be a curse. In the case of art made for a virtual reality platform, the medium’s breathtaking capabilities or “cool factor” sometimes serves as a substitute for the content itself.

Consider the “Evolution of Verse,” the short virtual reality experience on display at the Museum of the Moving Image exhibit, organized by The Future of Storytelling (FoST). Directed by VR auteur Chris Milk, the seamless short places you in the center of a placid lake, surrounded by green trees. The sun shines brightly. All of a sudden, in an explicit homage to the Lumières, a train rushes full speed towards you across the water. As the train hits you, it explodes into a streaming flock of black birds. The flock flies around the lake only to transform into fluttering streams of rainbow confetti, all in the blink of an eye. Quickly, the perspective changes: your disembodied gaze flies higher and higher above the lake, in a bird’s eye view. Soon you’re being pulled up into a tunnel. The lake has disappeared, and when you turn your head, you are face to face with an oversized eternal baby, a nod to the end of Stanley’s Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. You sit in the palm of its gigantic hand—dead, reborn, transcendent.

Still from Evolution of Verse

It’s not that such a psychedelic trip is unconvincing. On the contrary, the immediacy and illusionism of VR renders these hallucinations surprising, astounding, and inevitable. But these special effects also make a film like Verse ultimately feel like little more like a quick trick, showing off what the medium can do through linking together stock images. It’s not unlike watching a 3-D action film that favors exploding debris over winning the audience’s mental attention.

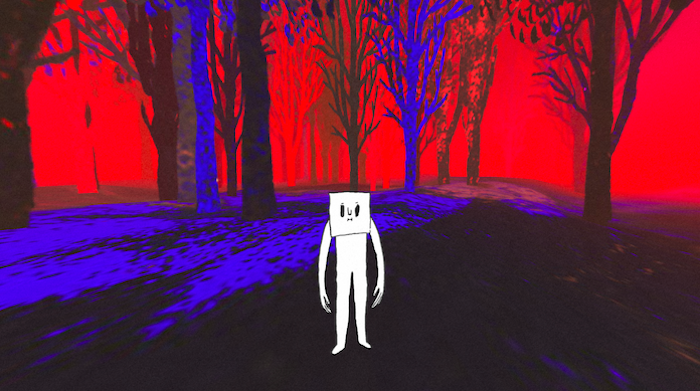

Where the spectacle of Verse remained shallow, another interactive journey displayed beside it, called Way to Go, reverberated with emotional depth. Storyteller and Sigur Rós collaborator Vincent Morisset's journey game constantly innovated with the immersive form of VR to produce a work of poetry in motion. With no set goal, you take a mystical spirit walk, as flashing lights and beating sounds play in sync to your movements. At once a musical composition and an open-world game, Way To Go makes you feel as though you're seeing the world—a technicolor, shamanistic, textured world—for the first time. And this expansive world, as the game’s description promises, “maybe lasts forever.” Beyond language and without precedent, it’s deeply fun.

But the most impressive combination of mind-blowing illusionism and artful ambiguity I’ve experienced was The Machine to Be Another. On view at Tribeca Film Festival this past April, the machine is exactly what it sounds like, allowing participants to swap bodies with another through an embodied VR “performance.” Designed by BeAnotherLab, an international group of scientists and artists, the machine reveals the radical differences between VR, video games and HD film experiences. Unlike in a film or game, the machine’s performances allow you to swap bodies with your boyfriend or get inside the head of a woman you’ve never met. In my case, I opted for the latter, trading perspectives with Shoko, a young woman about my age from Japan.

Once I put on the headset, I was—as far as I could see—in her body. When I looked at my hands, my legs, my bodies, they were hers—which is to say that for the moment, hers appeared to be mine, and vice versa. Partaking in a series of strange exercises through the lens of another’s body—from holding water balloons to looking at each other, which is to say ourselves, in a mirror—we stumbled around the performance space as though awaking from a strange Lynchian dream. Active participants, with our multiple sensory organs completely engaged, we were able to take advantage of VR’s unique perspective-granting abilities, while also wandering, as in Way to Go, through a playful, uncertain world. As Marte Roel, one of the lab's experimenters, explained to me over Skype, “We’re not as concerned with the specific technology as we are with the advancing of experience and expansion of subjectivity.” This experiential emphasis is what makes the performance, and the future of art with VR, so exciting.

Still from Way to Go

Ultimately, there are still kinks to work out in terms of the design aspects and types of realism that will work best in virtual worlds. Will we favor surreal experiences or worlds that closely simulate our own? Action epics or quiet art-house journeys? Or both?

Already it’s clear that promising experiments in virtual storytelling—at once tacky and sublime—are taking hold as artists begin to design for these virtual worlds. Touch, sniff, click, scratch, and see for yourself, at the Sensory Stories show in Astoria, Queens. Head there before July 26 not only to try the virtual reality experiences, but also to engage with the interactive films, touch-responsive games, and strange digital stories on view. A promise: it’s not like any train you’ve seen before.

All images courtesy of Future of StoryTelling