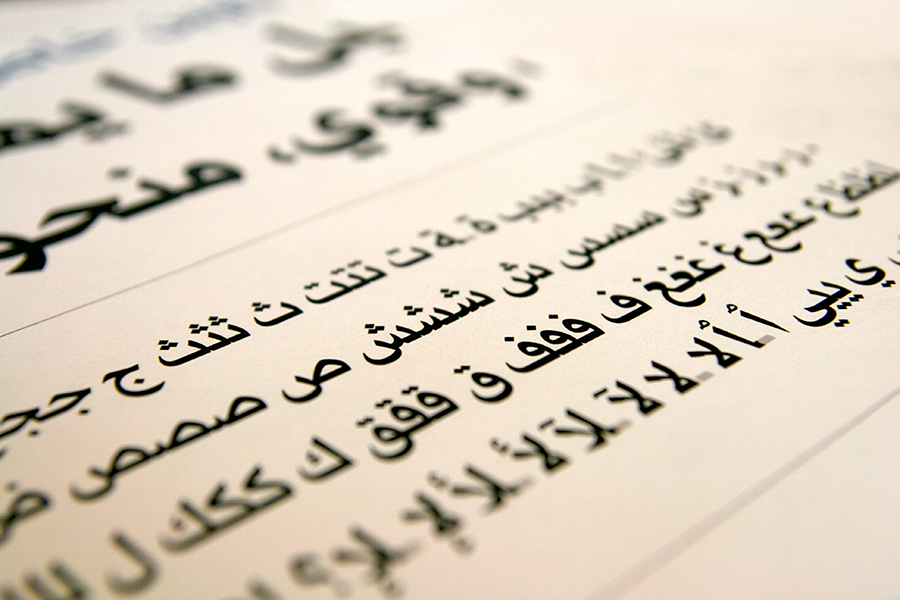

Visualisation of eye movement in Arabic as part of Nadine's research into legibility and the reading of Arabic on screen. Image courtesy of Nadine Chahine.

On March 14, 2012, I went to the taping of The Daily Show with Jon Stewart. I had always been a big fan of the show and organized my travel to New York to make sure I’d arrive on time for the taping — but almost didn’t make it. Once seated in the audience, I started chatting with the people around me telling them how I had to run through the airport make it on time. I joked that as an Arab you’re really not supposed to run through airports in the U.S.

One woman, upon hearing that I’m an Arab, exclaimed: “Oh but you look so nice!” I must admit that this is the best compliment-insult combo I’d ever been given. Does being an Arab preclude one from being nice? I grew up in Lebanon and have spent the past 15 years living in Europe and traveling the world quite extensively for my work as a type designer. I’ve been lucky in that I have not been seriously affected by increased hostilities against Arabs. Yet, for so many, it’s become increasingly difficult given the rhetoric of recent elections and politics. And the aforementioned example provides a glimpse of what it’s like to be an Arab in the U.S. — even in the comfortable confines of a fairly liberal show like The Daily Show. There’s often a stigma associated with being from an Arabic country.

It’s tempting to blame the current degeneration of Arab representation in the U.S. on the current political climate. And, while it does play a big role, the seeds were planted quite some time ago. For decades, U.S. foreign policy and the Arab public have been on opposite sides of one too many conflicts in the Middle East. For many years, Jon Stewart was the only voice in U.S. media that I could tolerate because I thought he was fair and had a way of balancing U.S. views, while recognizing the human cost of U.S. military intervention in the Middle East. I also welcomed the election of Barack Obama as he too was fair in how he portrayed the Middle East. He recognized that we are real people, with real concerns as well as aspirations, hopes and dreams. We are not the monsters under the bed that we’re often made out to be.

I believe that we can differ as cultures but we can still respect one another. I am one of numerous examples of an Arab professional working for an American company. I have immediate family members who are now naturalized American citizens and the interconnections between our cultures are many and almost always positive. Governments and political alignments come and go, but the people and their culture remain. There is so much that unites us and so much that can bring us closer, so it is quite frustrating to see the fear and distrust festering on both sides of this relationship.

It is heartbreaking to hear about people being removed from flights for speaking Arabic. Or being killed for being mistaken as an Arab. The profiling of the Arab as a terrorist, the travel ban of entire nationalities… surely this is not the answer? We must look to elevate this conversation, to open our eyes and our hearts to that which connects us, to recognize that there is more than one American, and more than one Arab. In my work I have repeatedly asked myself, “Isn’t there space for more than one Arab narrative?”

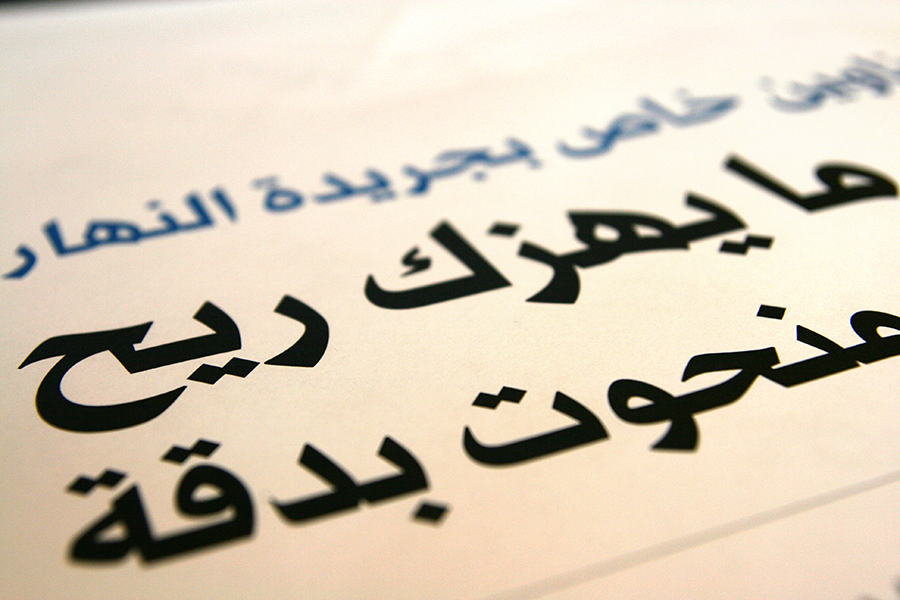

The typeface Gebran2005 designed for the An-Nahar daily in Lebanon. Images courtesy of Nadine Chahine.

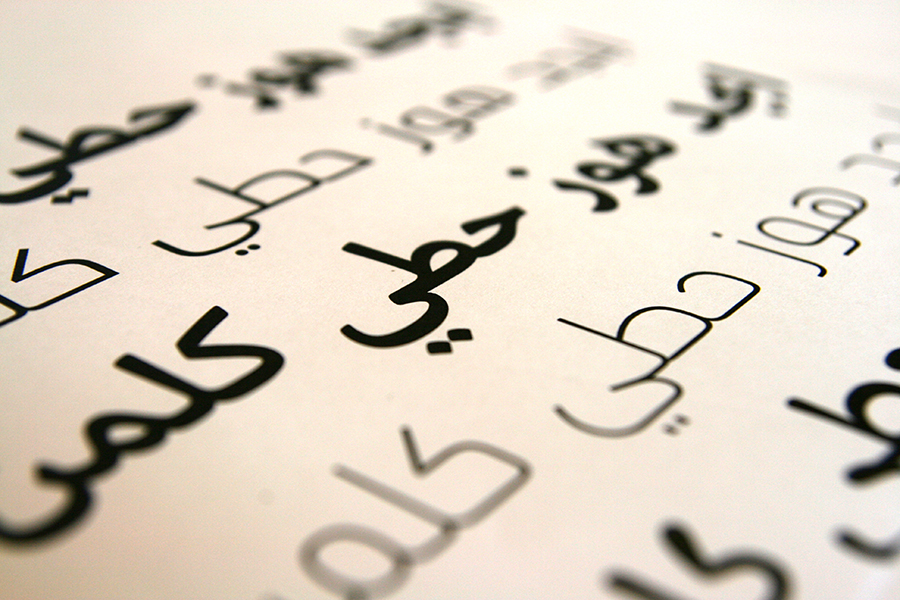

I design Arabic typefaces, and when I was studying Graphic Design in the nineties the Arabic designs we had were very limited and quite traditional in scope. Typography is the voice with which we speak. At the time, there were no options to design in Arabic and be contemporary, or informal, or hip or even businesslike. We were confined in our typographic voice, and thus our written communication, to the very traditional and often poorly designed typefaces and this did not sit well with me. Surely, we can be more than this? Clearly, we Arabs can be modern, can build businesses, do scientific research or just let our hair down and have fun.

Every typeface I’ve drawn has been a rejection of that confinement and an exploration of what a modern Arab voice can sound like. Every letter I draw is a wish for a better future. Type is such a critical part of culture and can convey so much tone, personality and message just by appearing on a page. It’s our voice. As Arabs, we need to work harder to find that voice, to soar high and to sing, and to break those misconceptions in every line of work that we do.

When I designed the headline typeface for the Lebanese daily An-Nahar as a dedication to its assassinated chief editor, the design was a statement in support of a free press that is not intimidated by political assassinations. When I worked through my PhD on legibility studies for the Arabic script, it was with the specific intention that we try to optimize the design of text so that people read more, so that our literacy rates in the Middle East improve. When I design Arabic typefaces for corporate branding and communication, I am hoping that we are able to build businesses that are the foundation of a blossoming culture. However, I recognize that what I do is so small in the large scheme of things, is nowhere near enough and can’t even begin to address the scale of the challenges ahead of us. But there is that hope, that like-minded people from across the aisle would find one another, for dialogues to begin, for the wonderful connections that we have on a personal level to blossom onto the international one. Designers can play a big role in that conversation; enabling communication is what we do on a daily basis and while we might differ in how we personally relate to our jobs, we are citizens first, designers second.

We, both Americans and Arabs of all creeds and professions, need to have an open heart that is willing to listen. And we really need this dialogue to take place. We fear that which we do not know. And if we really want a way out of the turmoil that keeps escalating, we need to make the effort to know one another, to engage in open and respectful conversation. We need a media that is brave enough to tell the stories that might not be what its audience expects. We need to be strong in the face of rejection. We need to conquer the fear. We can only do this together. It often feels that a large swath of the public is not interested in depth, or reason or nuanced opinions. Only memes and Twitter meltdowns. And in that kerfuffle I keep wondering to myself, where are you, Jon? We need you.

Samples of Nadine's work in Arabic type design. Image courtesy of Nadine Chahine.

ps. I always start my conference talks with a disclaimer stating that my political views are my own and not that of my employer, as almost every talk I give about design has politics in it. It’s the same in this case, but added here as a postscript.

This article was curated by Design Observer Editorial Board member Ashleigh Axios.