Tetiaroa from the air. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

The Brando. That’s the exclusive resort, opening next year, that will finally realize Marlon Brando’s vision of building an “ecological utopia that is energy-autonomous” with “47 deluxe bungalow villas each with private plunge pool ” on Tetiaroa, the Tahitian atoll he once owned.

Or, so the developers say.

An intriguing new book has arrived just in time to turn those glamorous claims into disturbing nonsense. Ecological? Brando’s vision? Absurdly unlikely on both scores.

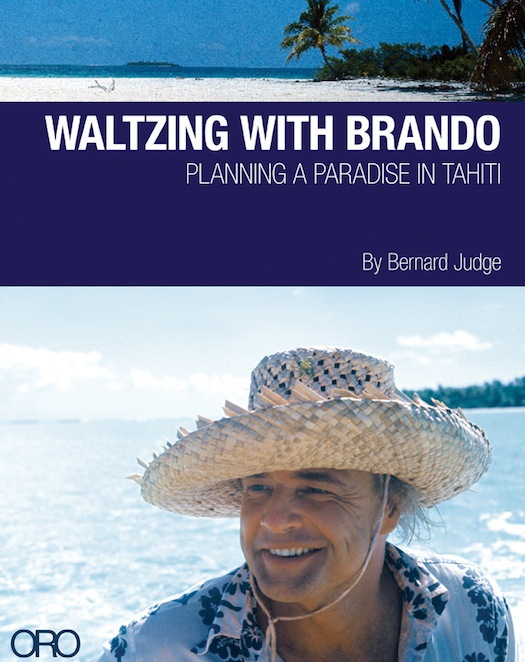

In Waltzing with Brando: Planning a Paradise in Tahiti (ORO Editions), Los Angeles architect Bernard Judge explains why Brando bought the atoll in 1966, then hired him as its master planner in 1971, and how they spent the next couple years trying to make the place somewhat habitable (by a couple dozen people or so) “without screwing it up.”

No can do. Turns out, an atoll — perhaps the loveliest of all geographical confections — is also exquisitely sensitive, and unapproachable, too. The five-mile-wide atoll of Tetiaroa is a lagoon full of 13 little islands (motus) ringed by a huge coral reef. There’s no harmless way to cross that reef. And once on the islands, there’s no pristine way to perform the simplest tasks of survival — drink fresh water, make waste — without disturbing, for starters, the high water table only one foot below ground level.

The idea of building-as-invasion may not sound radical now, but back in the ’70s, ecology existed mainly in the fevered, socialist minds of academics sorting out new evidence that industrial progress — lumbering, mining, drilling — decimated habitats, and not in a good way. In his book, Judge reminds us just how recent the notion of green living really is, while the marketing prose for The Brando, a “luxury eco-resort,” shows how surreal, and downright specious, green promo has become. Does this downturn signal the end of the environmental movement already?

On Tetiaroa, Brando and Judge wrestled with the contradictions of making paradise accessible, as both as inspiration and warning, as they altered it in ways they were unable to measure. “We had to understand as best we could the interdependence of each part of the system,” Judge wrote. “Without healthy coral, there would be no reef; no reef, no motus; no motus, no birds; no seabirds, no tuna fishing for the Tahitians.” According to Judge, “It was one thing to say ‘no pollution’ but quite another to follow through with it. As soon as anything new invades an ecological system, ‘pollutants’ follow.”

Judge helps us absorb this certainty — viscerally — by taking us through months of tent-camping, usually with his wife and daughter in residence, cooking, composting, rat-wrangling, surveying, drawing and building on Tetiaroa as it slowly discloses the intense pleasures — and consequences — of messing with Eden.

An exercise in futility? Yes, and that’s the beauty of this saga. Earning our empathy as he details the daily challenge of tropical housekeeping, Judge reveals the soul of an architect. He describes, with candid self-deprecation, the pitfalls of building a tiny civilization from the sand up. In the process, Judge manages to deliver an important fact we’re loathe to believe: There’s no such thing as re-visiting paradise. Step into it for a peek, and you’ve already altered it in unknowable ways for an unforeseeable future. (Step into it for a stay in The Brando’s super-swank, air-conditioned villas-with-pool and — well, why not just stay in Beverly Hills, for God’s sake?)

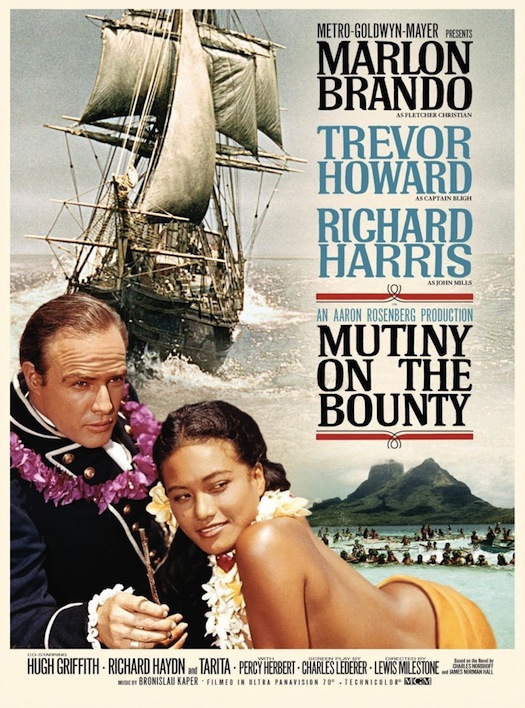

What did Brando really want from Tetiaroa? Judge says he bought it after spotting it on location for Mutiny on the Bounty “to get away from all the bad things in life.” Brando hoped to live there, Tahitian-style, in an unelectrified grass hut with hammock, while figuring out how preserve the atoll intact for posterity. (Actually, Brando could buy only the islands, since the government retained ownership of the lagoon and reef.)

According to Judge, Brando started to worry about the fate of Tahiti while living on the main island with his Tahitian amie and children. There he watched modernization wreak havoc: fish in the lagoons became tainted by toxins washed down from valleys where garbage dumps, sometimes ablaze, were hidden away. To Brando, Tetiaroa represented a last chance to save a remnant of undamaged Tahiti for future Tahitians. He also wanted to use Tetiaroa to spread the idea of keeping nature intact, and welcomed scientists and students who could use that sealed setting to figure out how to take care better care of any ecology.

Soon, mission creep set in. With erratic funding, Brando wanted to do a lot of good with minimal impact. “It started with a couple huts for Marlon and a few visitors. But it took a bunch of people to keep that going. And it took money to house those people and pay them.” Judge said. Next it was decided that more people, in the form of paying visitors, might help support the complex enterprise of making Tetiaroa accessible on a very small scale. So, avoiding the word tourism, Judge began building visitation amenities to house strangers for a modest fee, when the island was empty of Brando and his guests, which was most of the time. “You couldn’t call up from Kansas and reserve two weeks, but you could ask for an overnight, if you were passing through the Tahiti airport,” Judge said.

Eco-resorts didn’t exist yet, but Judge studied two sorts of bare-boned venues — Treetops Lodge in Kenya and the early Club Meds — where tourists gave up creature comforts in exchange for the thrill of sampling wildernesses from tents or barracks with common baths. With “a contractor and six guys,” Judge began to assemble the unassuming Hotel Tetiaroa Village: a dozen thatched bungalows, public toilets, kitchen, bar, and a welcoming hut on the island’s only thoroughfare — an airstrip for small planes.

Planes were the only means of reaching Tetiaroa without crossing the reef, a dangerous enterprise for the environment and people, too. But using planes to import all food, and retrieve the food packaging, created expensive air and noise pollution without helping the village to become self-sufficient. With researchers, Judge and his crew experimented with methods of raising food for the atoll residents, while creating new agricultural industries at a modest scale as a source of income for island maintenance. They tried to cultivate lobsters and crabs, raise fish (aquaculture), and plant vegetables with scant irrigation (nutriculture) without much success. At the same time, they undertook conservation projects to protect the breeding grounds for huge populations of sea birds and sea turtles, atoll tenants and visitors for thousands of years. What would become of them?

Indeed, what became of Brando? After he hired a hotel manager, and Judge returned to his real life in LA., some destructive years followed. A hurricane swept away much of the settlement. And unable to escape from the bad things in life just as they became most excruciating, Brando stopped visiting Tetiaroa for 30 years, from 1974 until his death in 2004, as court cases followed one lurid family tragedy after another. In his absence, however, his dream essentially came true, if only for a short time. Tahitians visited Tetiaroa, Judge says. “Most of its visitors then were older people who brought their children to show them, proudly, how simply, and how well they used to live before automobiles and electricity changed everything."

Now that Tetiaroa is the hands of U.S. developers courting the wealthiest global clientele, most of the Tahitians there will no longer be day-tripping families, but security-cleared personnel on the resort payroll. Brando’s vision? Time to rewrite that script.

Author’s note: No, Waltzing with Brando is not a self-published vanity tome as you might suspect. It’s a unique hybrid — illustrated coffee table paperback plus memoir — printed by ORO Editions, a specialist in architecture books. A fresh, wide-eyed narrative combined with lots of vintage slides from the 1970s, digitally converted into saturated images (including a few discreet shots of an off-duty Brando) made this read feel like an exotic voyage and a Peace Corps stint rolled into one. In short, it’s the most absorbing, non-pious, environmental saga I’ve read since Kon-Tiki. And the six-minute trailer from Visaya Films, for a documentary of the same name, makes me want to see two more hours.