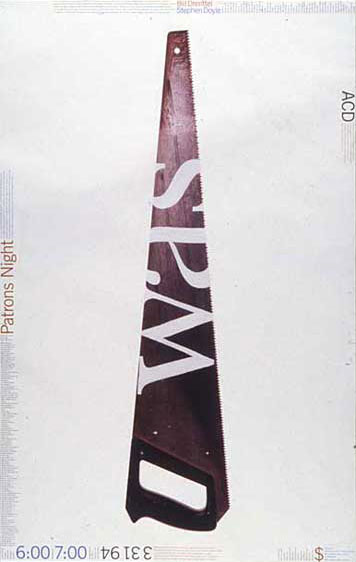

Stephen Doyle, "WAS/SAW Poster," American Center for Design, 1994

Between 1985 and 1997, I was partners with Stephen Doyle and Tom Kluepfel at Drenttel Doyle Partners in New York City. While Tom stayed home to mind the shop, Stephen and I did endless road trips, making presentations, mostly for the AIGA, in cities across the country. Often we'd be asked to design our own posters for these events.

I came to work one day in 1994 and Stephen was masking out the word WAS onto the face of a lumber saw. He said watch this: and he painted the masked area white. This was my first experience with Stephen's word art, a dyslexic's nightmare, the simplest of words translated into a three-dimensional graphic form.

The Was Saw. Or the Saw Was. Is it graphic design? Or a tool for murder?

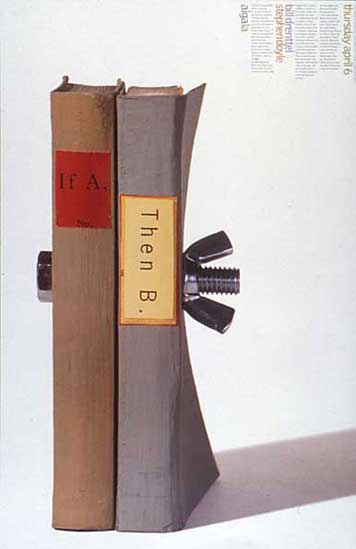

Stephen Doyle, "If A, Then B Poster," AIGA Los Angeles, 1995

Stephen Doyle is a graphic wordsmith.

Stephen did another poster in 1995 for AIGA Los Angeles where he bolted two books together, and added a bit of Wittgenstein across the spines, "If A, then B." Two partners bolted together in partnership? Craft and strategy? Design and commerce? I still have the actual object, the two books bolted together, as one of the favorite objects in my library.

After my departure, Doyle Partners continued to play with word forms across many projects, and it's hard not to open The New York Times and immediately recognize a piece of graphic artwork as the work of Stephen Doyle. It's usually just a word, or a word transformed into another word. Usually it's photographic, a real object redone — and not a trompe-oeil in Photoshop.

There is something about contemporary culture where words become separate from their meaning, or acquire so many meanings as to become meaningless. The weekly presentations for the William Safire "On Language" column in The New York Times are an example of language being turned into editorial art: language is the assignment. In this Op-Ed World, words alone are evocative. They do not need commentary as their graphic form is its own commentary. There are other practitioners of this art — Chip Kidd, Michael Bierut, Paula Scher, to name a few — but Stephen Doyle has always seemed to me to be the most obsessed with making individual words meaningful, even transcendent, in a graphic form. If Op-Ed art is the new public form, Stephen has a calling; he is the master of the word made meaningful.

In recent years, Stephen has begun to make sculptures of words, passages from Machiavelli, entire literary works by Willa Cather. Here, a graphic designer explores how far the making of words can migrate into other forms. I've never read The Professor's House, but I know Stephen Doyle's reading is different from mine, from the book in my library.