Whatever needed doing at the mortgage company, I did, particularly if nobody else wanted to be bothered. Since I didn't have my own desk, I floated around, occupying whatever space was handy and empty. This was in the early 1990s, in Pittsburgh. The mad dash to refinance home mortgages had begun to cool. Whole suites were deserted, reminders of a time in the not-too-distant past when the company enjoyed more bullish days.

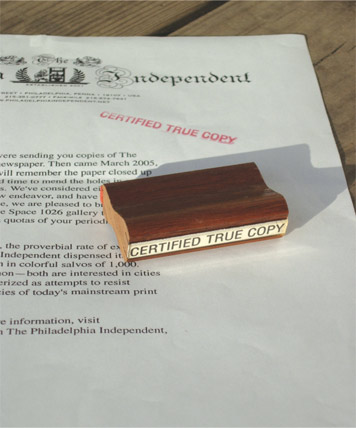

I searched every desk I sat at not only to fill the periodic lulls but also out of curiosity, to find pieces of other lives, workers before my time. One slow day, while pawing through an abandoned desk, I discovered this rubber stamp and knew immediately that I had to make it mine. Certified True Copy. How strange, I thought, and funny. How could a copy of something ever really be true?

My discovery was luck made manifest. I had recently started writing a story about Copy Copy, a fictional copy shop where a clerk named Tom Again worked the nightshift. Tom dreamed up grand-sounding theories like the Law of Copies, which holds, not originally, that life is but one long and steady decline. An original loses something when copied, Tom posited. A copy of that copy loses a bit more. The law of copies, Tom argued, was the dark twin of the myth of progress. He had ideas, as I had ideas then. And he was stuck, much as I was stuck. I took the stamp, thinking, I'll incorporate this into my work. I'll use it. In a moment of misplaced optimism, I even thought it might help me finish the story, like some magic talisman.

It didn't work. At least not as I hoped. I quit the job, left the story unfinished, and went on to other things.

This short essay is excerpted from Taking Things Seriously: 75 Objects with Unexpected Significance, a book by Joshua Glenn and Carol Hayes in which they and other writers discuss the importance of objects in their lives. This is the eleventh essay in a series to appear on Design Observer.