Advertising leaflet—The child’s first drawing book (Chicago: A. H. Andrews & Co., 1878). A typical example of Aesthetic-era artistic printing, incorporating exotic display fonts, stylized floral ornaments, asymmetric design, and “cascading” typography.

The exhibition “For Art’s Sake: The Aesthetic Movement in Print and Beyond”, currently at the Grolier Club, surveyes the role of printing in the Aesthetic Movement. The focus is on materiality as much as content, emphasizing the variety of ways in which books, periodicals, and ephemera promoted Aesthetic principles, visually as well as textually. The exhibition is on view through March 11. — Eric Holzenberg

I was fascinated by the Aesthetic Movement before I knew what it was. As a child I was drawn to the art and architecture of the past, but I had the misfortune to grow up in a series of aggressively forward-looking communities where nothing was more than twenty years old; so in protest I developed a passion for Victorian design in all its aspects. After a long flirtation with the Gothic Revival, I began to look to the later nineteenth century, trying to categorize the types of objects that particularly attracted me, and determine where they fit in the history of decorative arts. (This was, and is, not so much a scholarly exercise as an attempt to arm myself with the vocabulary and other data I needed to collect more of these objects, and more efficiently.) About a decade ago, while acting as unpaid editorial assistant to my husband Henry in the course of his Master’s degree in the history of decorative arts, I came gradually to recognize and appreciate the exceptional artistry and wit of the Aesthetic Movement, an odd mix of antiquarianism and japonisme that captivated Oscar Wilde, inspired William Morris, and dominated what the designer Lewis F. Day called “the arts not fine,” in the period 1870-1890.

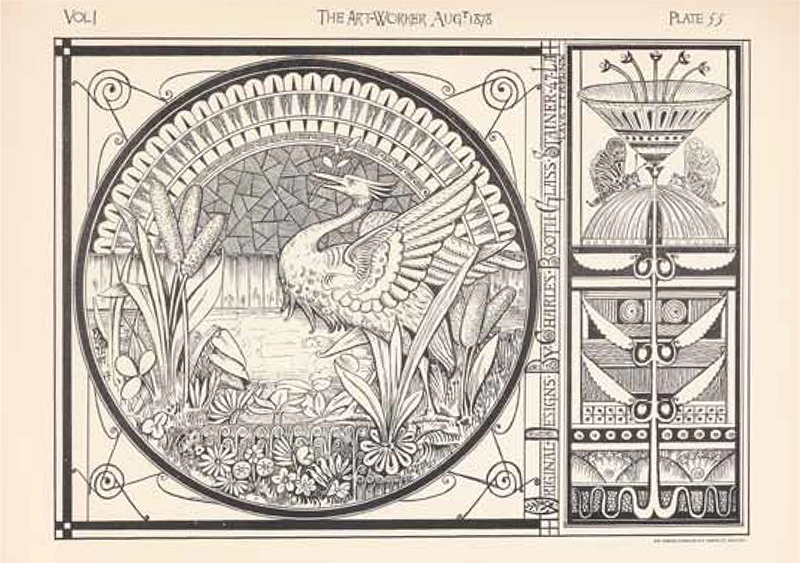

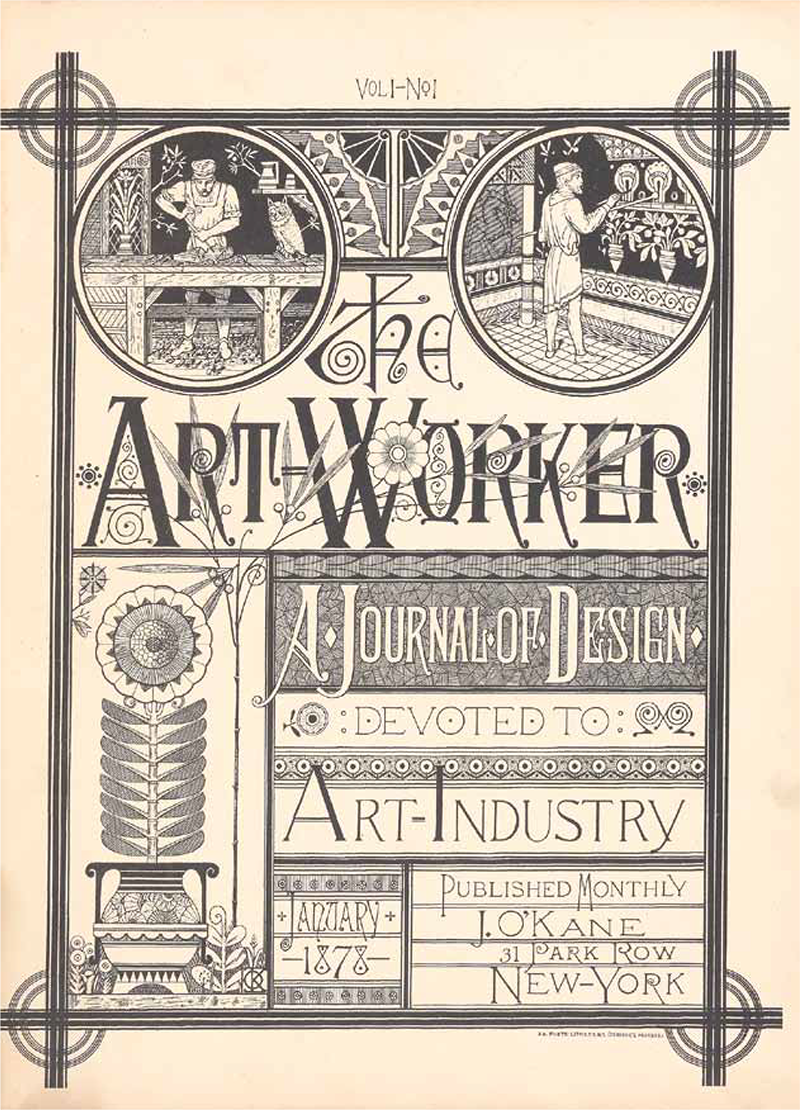

The art–worker: A journal of design devoted to art–industry. New York: Published monthly by J. O’kane, January 1878[–December 1878]

Why the Aesthetic Movement? As with most collectors, the subject chose me, not the other way around. The more I learned about the movement, and the more objects I saw, the more these designs and shapes captivated me, electrified me, made me laugh out loud. It was clear that this entertaining mash-up of idealized past and exotic present represented something new in nineteenth century decorative arts, a decisive break in the plodding series of revival styles that had characterized Victorian design through the 1860s. And although the Aesthetic Movement is now more than a century dead, I cannot help seeing it as the Aesthetes did: a fresh approach to ornament, borrowing indiscriminately from all periods and all nations, imitating nothing directly, but inspired by everything; its motifs, shapes and colors intended to give pleasure, but not to educate, or “improve”—Art for Art’s Sake.

I have always been a book collector, and as I explored my new interest it seemed to me that the books of the Aesthetic period never got as much play in exhibitions and catalogues as I thought they deserved. The glimpses I had of bold, quirky, sometimes mind-bending examples of binding, illustration, and “artistic printing” produced in this period, coupled with a growing sense of the importance of pattern books, how-to manuals, prints, and ephemera in the transmission of Aesthetic principles and motifs to artisans and members of the artistic public, showed me where I should concentrate my efforts, and my limited funds.

The collection from which this exhibition is drawn is now a decade old, and consists of roughly 500 printed items, including monographs, pattern books, periodical issues, and ephemera, plus about 100 examples of Aesthetic-era china, silver, brass, and furniture whose design or manufacture is connected with print in some interesting way. It has reached a stage where it can begin to be a useful survey of the “Aesthetic book” broadly defined, considered not only as the embodiment of Aesthetic principles, but also as the chief mechanism of the movement’s rapid rise, surprising popularity, and almost universal, though fleeting, dominance in the decorative arts of the later nineteenth century. It is not a comprehensive collection, in part because, as an Aesthete, my policy is to acquire things, not because they are significant, but because they delight me. I offer “For Art’s Sake: The Aesthetic Movement in Print & Beyond” in hopes of sharing that delight.

The art–worker: A journal of design devoted to art–industry. New York: Published monthly by J. O’kane, January 1878[–December 1878]

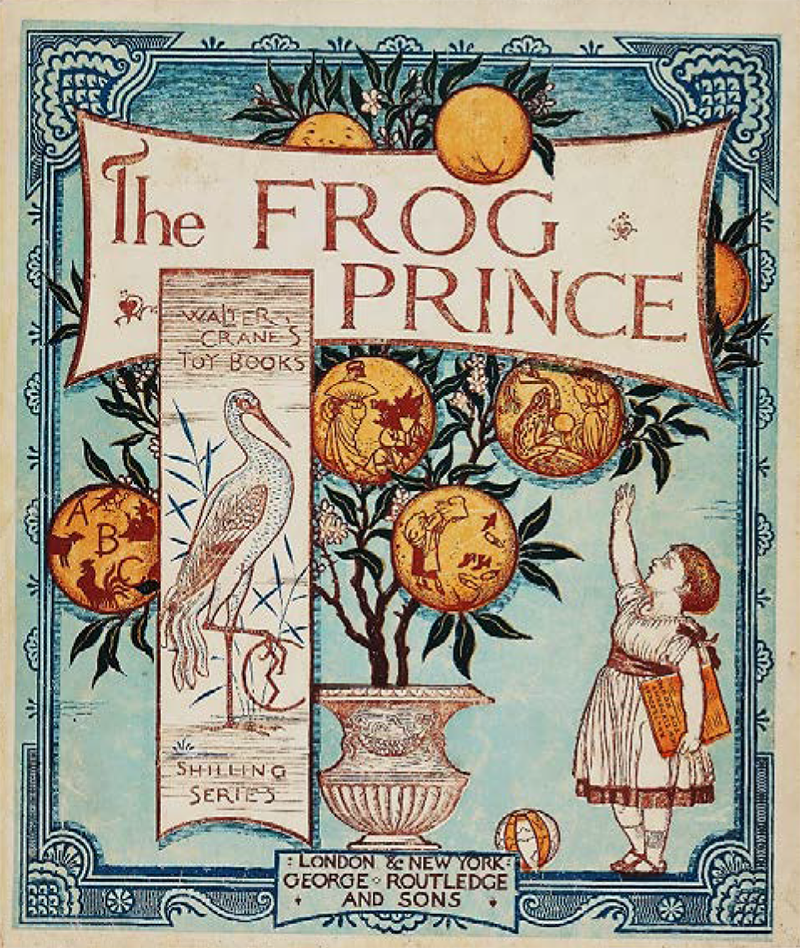

Cover design for Routledge’s “Shilling Series” of Walter Crane’s toy books, ca. 1875, incorporating the artist’s distinctive WC monogram and crane device.