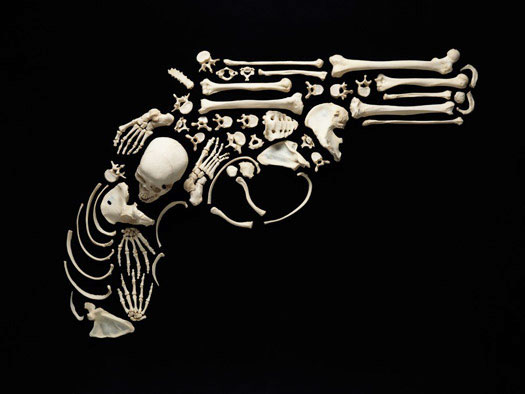

Gun by Francois Robert

Francois Robert was at an auction in rural Michigan. It was the mid 1990s. A school was selling off supplies, and Robert was looking to buy some furniture for his studio. "I was interested in buying some lockers, and they had three for $50." Two of the lockers were empty, but not the third. When Robert opened it up, he found a human skeleton.

Francois Robert was at an auction in rural Michigan. It was the mid 1990s. A school was selling off supplies, and Robert was looking to buy some furniture for his studio. "I was interested in buying some lockers, and they had three for $50." Two of the lockers were empty, but not the third. When Robert opened it up, he found a human skeleton.

The skeleton, fully articulated and in reasonably good condition, must have served as a teaching aid in a science class. Francois Robert is a photographer. He took the lockers back to his studio in Chicago. It took him years to figure out what to do with the skeleton.

"Bones have always fascinated me," says Robert. His portfolio has always included images of animal skulls, recovered from the desert. He once spent five weeks photographing skulls in the collection of the Field Museum of Natural History. By 2007, the recession was taking its toll. "I had so much extra time. What was I going to do with it?" He turned to the skeleton in his locker.

Robert realized that his skeleton was limited: it was wired together for display. He decided he wanted a skeleton he could take apart. Online, he found a source for disarticulated human skeletons, and he traded his in, and took delivery of a box containing 206 separate bones, each the real thing, not plaster or resin.

Since then, Robert has spent hundreds of hours working with those bones, arranging them painstakingly into striking, iconic shapes, each five or six feet wide, and photographing them with a 4x5 Hasselblad rigged to a boom to provide a bird's eye view. He calls the resulting images "Stop the Violence." Each shot takes a full day to set up. "I was on my knees for all of 2008," Robert remembers.

The results are beautiful and haunting. Robert confesses that more than anything else he is motivated by the fear of death. "The bones are something left behind, a form of memory," he says. "I try to treat that person on my studio floor with respect."