In October of 1915, five months after Italy’s entry into World War I, Vera sent a letter to Palma announcing that she and Ezra would sail home in early November. They were to embark from Naples, she wrote, sailing with their now three-year-old daughter Renata on the SS Ancona, leaving late the evening of November 6th.

Shortly after 1pm on November 8th, the Ancona was torpedoed by German U-Boats. 272 people lost their lives that day: among them, it seemed, Ezra Winter and his young family.

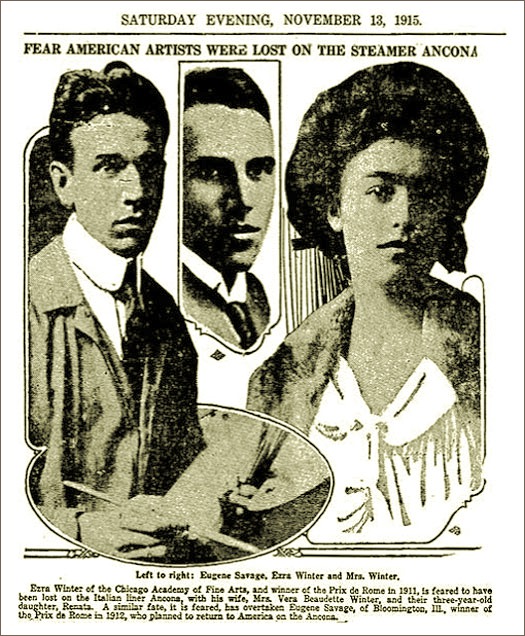

New York Tribune, November 13, 1915

For several days, the American newspapers carried stories of the stricken ocean liner. Photographs of the Winters — and of fellow traveler Eugene Savage, the American painter who’d won the Rome Prize a year after Ezra — were plastered everywhere. It was a tale of unimaginable tragedy, except for one thing.

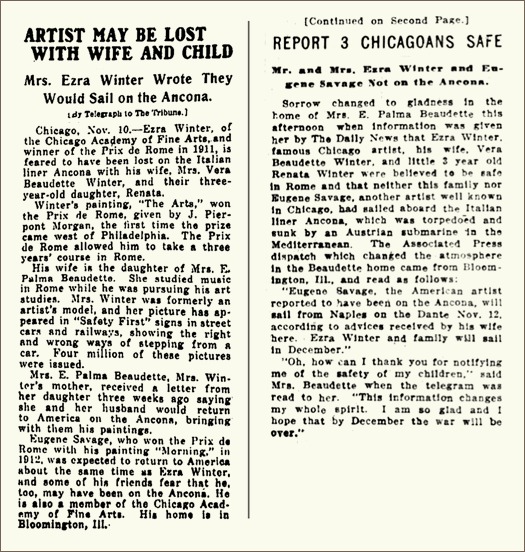

None of them had actually been on the SS Ancona.

It’s not entirely clear why the young couple chose not to telegraph their families right away (perhaps they did, and wartime communication proved an inefficient means to do so) but for whatever reason, they were presumed lost. For Ezra — young, ambitious and accountable, it seemed, to everyone — it was more than an extraordinary bit of good fortune: it was an unexpected reprieve, a chance furlough. If not in the literal sense, Winter was, at least figuratively speaking, very much lost at sea. And he had never been happier.

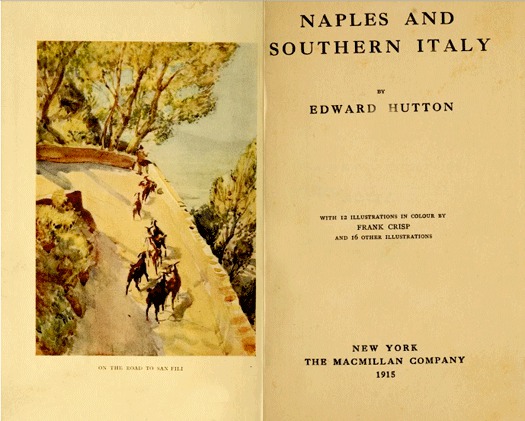

Traveling from Rome by train that autumn, Ezra and Vera arrived on the coast where they might have been guided by the luscious watercolors of Francis Crisp — a promising young British painter who had been killed earlier that year, fighting at the front.

Crisp was 33 when he died.

Crisp's obituary, published in The New York Times January 15, 1915

But Ezra Winter, not yet 30, is very much alive. And so is the city of Naples, a place of intense vibrancy “whose life is merely life, without dignity, beauty or reticence, or any of the nobler conventions of civilization.”

Excerpt and title page from Hutton's Naples and Southern Italy: on left, painting by Francis Crisp, 1915

And so, with wife and small child in tow, Winter embraces Naples like a fugitive. On borrowed time, they tour the coast — from Naples to Capri, Sorrento to Positano — a trio of self-exiled wanderers. The sea air is still warm, and until the winter rains descend in late November, the breezes will intoxicate them along the meandering coastline path.

(Please wait while the video loads.)

Film Courtesy of Travel Film Archive. Music: Béla Bartók, Suite Op.14 Sz. 62 (1916) - I. Allegretto, recorded by Gyula KissBy early December the whereabouts of the young artists are discovered and their formerly bereaved parents are interviewed in the American press.

Excerpts from stories in the New York Tribune, 1915 and early 1916

The young family returns to America for a brief sojourn before sailing back to Italy in early 1916. Upon his return, Winter travels to Arezzo and Perugia, Orvieto and Siena, Assisi, Florence and Pompeii. He is wildly productive, setting up his easel in cathedrals and museums and copying as many great Italian paintings as he possibly can. In this, his final year as an Academy fellow, Ezra Winter loses himself not so much at sea as in the craft and construction of painting.

(A decade later, Ezra Winter will sail to the Antarctic, one of a dozen passengers seeking to collect specimens of arctic sea life for the Museum of Natural History in New York. Soon afterward, he will travel to the Carribbean with his friend, the American Naturalist William Beebe. And for decades to to come, Ezra Winter will associate the ocean with a kind of magical suspension of disbelief. He will yearn to recapture that feeling — if not the very reality — of being lost at sea.)

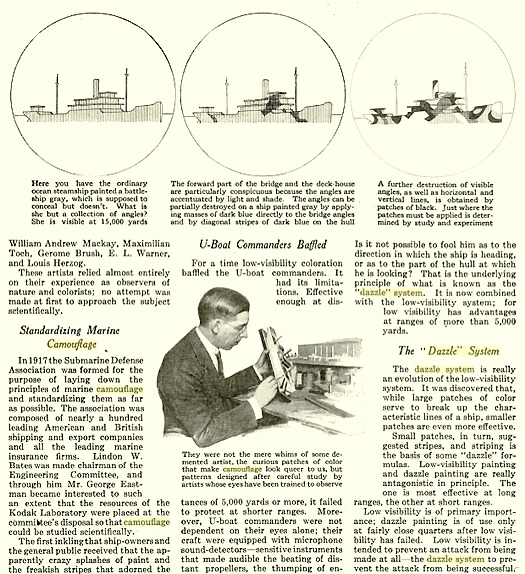

And then, all at once it seems, the European odyssey is over. Winter returns to the United States and settles with his family briefly in New York where he takes a position designing camouflage for the U.S. Shipping Board. He is part of the team responsible for developing a technique that would come to be known as the “dazzle” system: a formula in which patches of striped lines were strategically painted onto the hulls of ships in order to baffle enemy boats.

Popular Science, April 1919

In his first post-Academy professional pursuit, Ezra Winter is literally painting things so that they are hidden from view — intentionally lost against the horizon. Ironically, while the patterns are in fact mandated by the dispassionate scientific language of mathematical reason, the formal choices he must use lead him toward a reductive vocabulary of bold stripes and patches of solid color. This new visual language is far closer to the language of Klee and Kandinsky than of the Renaissance masters he has copied and studied.

Dazzle is, for Ezra Winter, a kind of modernism by proxy.

Typical example of a "dazzle" pattern on the side of a ship, courtesy Damian O'Hara

Modernism itself continues to beckon. It is now 1917 — the era of the DeStijl Manifesto and the first recordings of Dixieland jazz. Mary Pickford stars in Poor Little Rich Girl — in which she plays a wealthy child ignored by her parents until a brush with tragedy redeems them. Everything — even a Mary Pickford movie — is tinged by the imminent threat of danger and death.

(Please wait while the video loads.)

From Poor Little Rich Girl (1917) directed by Maurice Tourneur and starring Mary PickfordThe U.S. enters the war in April of that year, while overseas, poets and writers struggle to comprehend the irrevocable losses of so much young life. In the U.K., T.S. Eliot publishes Prufrock and Other Observations: a meditation on urban isolation and decay — and a lyrical elegy to the very notion of loss.

“I have seen the moment of my greatness flicker," wrote the poet, "and I have seen the eternal Footman hold my coat, and snicker, and in short, I was afraid.”

Wouldn't Ezra himself have been afraid, of what lay ahead and how powerless he was to control it? Afraid to embrace a new kind of making? Afraid to be a painter when the world was so clearly imperiled? How safe he must have felt to find employment as an artist, tasked with the very odd mission of disguising boats.

And yet, by early autumn, things are beginning to change. Ezra is invited by the Mayor to a dinner for the Imperial Japanese Commission to the United States where, seated at Table Fourteen, he dines on filet of flounder and Peach Waldorf. He is asked to participate in juries at The Cooper Union and the National Sculpture Society. He takes a studio near Washington Square, and begins to secure commissions. No longer the seafaring wanderer, Ezra Winter has landed on solid ground. He is back. And he is on his way.