Doug Powell: Jon, what brought you to Austin, how did you create the Austin Center for Design, and what happened in between?

Jon Kolko: I first came to Austin to join a company focused on enterprise software. Big, high-end, big projects: pricing, ordering systems, and supply chain management.

It was interesting for a young professional. Despite your age, they would throw you into consulting projects at an executive level. I remember buying my first dress shirt in order to have a conversation with the CMO of Bristol-Myers Squibb. I had no idea what I was in for. I wasn’t there that long, but my takeaway was a level of responsibility that was disproportionate to my ability. There’s a career theme there, as I look back.

DP: A theme of stretching yourself—whether you do so intentionally or find yourself in a situation that you’re completely unprepared for?

JK: Right. If you think about design, it’s often a situation with no real precedent, with no real boundaries or rules, and it’s sort of up to you to tame it.

DP: What was your job title?

JK: I was an Interaction Designer. I graduated with a master’s degree in human computer interaction, and my first job was in interaction design.

DP: I don’t mean to sound overly surprised by that, but in the late ‘90s, the notion that those two words “interaction design” were a thing, and that they were actually hiring somebody to do something like that, that’s notable.

JK: It was very forward thinking. My boss was a woman named Lynn Pausic, who graduated from Carnegie Mellon years ahead of me. She instilled a thinking about the relationship of people and computing, about humanizing technology. There’s an inherent weirdness in technology, and interaction design makes it familiar.

In many respects, the designer is the one that’s going to harmonize all of the information and data and make sense of it. There’s always been a demand for this skill set. Maybe the title “designer” is amiss for us. I’ve thought about that a lot and realized, “I’ve spent my professional career trying to get design credibility.” Maybe I should’ve capitulated, and called myself something else the entire time.

DP: That’s a question I ask myself a lot, too. Designers do a lot of correcting, or explaining, around design because of the word. It’s a tricky word, and loaded. It comes with a lot of preconceptions, and it takes a lot of decoding to get to people to have a meaningful conversation around it.

But after your first job...?

JK: My second job was with a startup. It had $11 million in funding, and was focused on demand-planning software. Very simplistically, demand-planning software solves problems like “How does Best Buy know how many units to have on the shelf at any given time?” All the way up and down the supply chain. It was an exciting time to be in a startup. But like all the dot coms, they spent $11 million in Aeron Chairs and all the metal decoration you can get.

DP: That must have been a sexy office.

JK: It was. We burned through that $11 million in about a year. That company folded and I went from there to another startup. That didn’t really work either. At that time I was starting to do what a lot of 25-year-olds do. They say, “All right, I’m done with design. Never mind.” Then they go open a yoga studio, or something. So I wondered, “What’s my yoga studio?” I didn’t have an equivalent of that.

Very naively I thought, “What’s easy? Teaching is easy. All right then, what school in the country will hire me to teach, given that I have no teaching experience and I look younger than most of the students?” Turns out, Savannah College of Art and Design would hire somebody like that. And for that, I owe a lot to SCAD, for taking a chance on young professors.

They hired me, and I moved myself and my wife over to Savannah. I started teaching Industrial Design classes and was eventually able to build out a revised curriculum for the department. I was there for about five years, and I grew a ton being there. I think the growth has a lot to do with teaching.

When you have to teach somebody something, you can’t write them off as being dumb. It’s very easy in corporate America to say, “Well, that person is stupid. That’s person is not gonna get it.” But in academia, they’re stupid on purpose. That’s why they’re in school, right? And it’s your job to help them know things. That was an eye-opener for a very arrogant 25-year-old.

DP: Humbling.

JK: Humbling, absolutely humbling. Actually, very exciting, too, because what you find is that you can’t simply teach how you would have learned. That works with some percentage of the students, but the others are still ignorant. So you have to come up with a new way of teaching. With a classroom full of 20 designers, it might actually take 20 different ways to teach a concept.

AC4D student project True Story helps you collect stories from your aging family members to understand their values and help them make choices about their future.

DP: I think it’s interesting that teaching was a pivotal point for you. It’s true of a lot of designers who have longevity in their career. Somewhere along the line, being a teacher resets their understanding of what being a designer means. “This is all very intuitive to me; I do it every day. Now how am I going to explain it to those 20 people who have 20 completely different points of view?” That’s a powerful experience.

JK: I’ve read that a majority of my design heroes have, at some point, taught. And when I look at the figures that shaped how I approach design, they’re academics, primarily. They’re not necessarily designers, they’re designer/teachers.

DP: So you were at SCAD for five years?

JK: Yes. At some point, it got easy and I got complacent. I stopped learning, which is on me. So I quit, and I came back to Austin to work with frog. And frog was one of these companies that you hold up like, “This is a great thing.”

DP: Tell me more. frog has had a great case of characters, like Robert Fabricant who was there for many years. There’s some great, legendary designers, and amazing personalities who must have been in the mix when you were there.

JK: Totally. We had a lively studio, a lot of attitude, in a good way. I think you need a lot of attitude to participate at the level of consulting there. It was fun. I worked on HP, Disney, Microsoft, AT&T, Nielsen, and all sorts of big brand companies. I racked up a lot of frequent flyer miles.

I spent a lot of time there with Fabricant, formalizing education curriculum internally, and then externally, around facilitation. Engaging clients, not just as the expert consultants, but leveraging participatory design activities. So the designer’s role shifted a lot from being heads-down in the studio with headphones on, to being a figure-head. You got up in front of a room, and you led a group toward a solution on the whiteboard. Rather than a designer standing up at the end of the project unveiling their new logo, and saying, “That’ll be $100,000.” There’s a new approach. This new way of thinking takes the posture of: “I want to participate in that process, so that I own the result at the end. I really feel like it’s intimate to me.”

DP: So where does AC4D come into the picture?

JK: Right around there. frog, IDEO, and all these companies are very good at getting PR for social and humanitarian work. And very good at doing high profile, glamour shots of someone in the middle of Africa holding a big plastic green thing that saved the world. They’re very good at spinning PR around those things. I think a lot of the designers at these companies are enamored with working on impact projects. Especially millennials demanding to do something of worth. When I was the Creative Director at frog, I was constantly asking, “Why do people want to work on those so bad?” I would get my kicks off of pretty much any project. I would get excited about working on AT&T, so why didn’t everyone? And the answer is “impact.”

DP: I think that’s part of it. But I also wonder what buzz these millennial designers are after. I agree with you, I can get a buzz in lots of different projects. But I think the younger designers feel, “I want to be so close to that person that I’m designing for. And if I’m one or two, or six or 10 layers away from that, then it doesn’t feel as fulfilling.”

JK: I think it’s both of those things. There’s this sense of, “I want to have a human connection, and I want to be in charge.” And I think also there’s this expectation that the work being done is valuable. It’s a very arrogant expectation. It’s an attitude like, “My time should be spent working on something I consider valuable, because I am valuable.” That’s very millennial-ish.

But to finish the story: Everybody wanted to work on “impactful” projects. But there aren’t enough of those in a design firm. And frankly, nobody really knew how to do them. So the seed of Austin Center for Design was, “How can we create an educational institution that teaches autonomy?”

With the skills to be autonomous, students can pursue paths towards that type of work. Rather than going to a firm and hoping that they get resourced on the one-tenth of “impact projects” at the firm, they can craft a path towards leading one themselves.

DP: This is an incredibly evolved idea. How do you get from that idea to AC4D?

JK: It’s very naïve in hindsight. Who the hell starts a school? Who does that? And actually, when we started, it took about a year of conversation with the oversight board that we work with—the Texas Workforce Commission—to help them understand what it is we were trying to do. Because they’re used to licensing charter schools, or truck driver schools, but definitely not design schools. We worked on that for a long time.

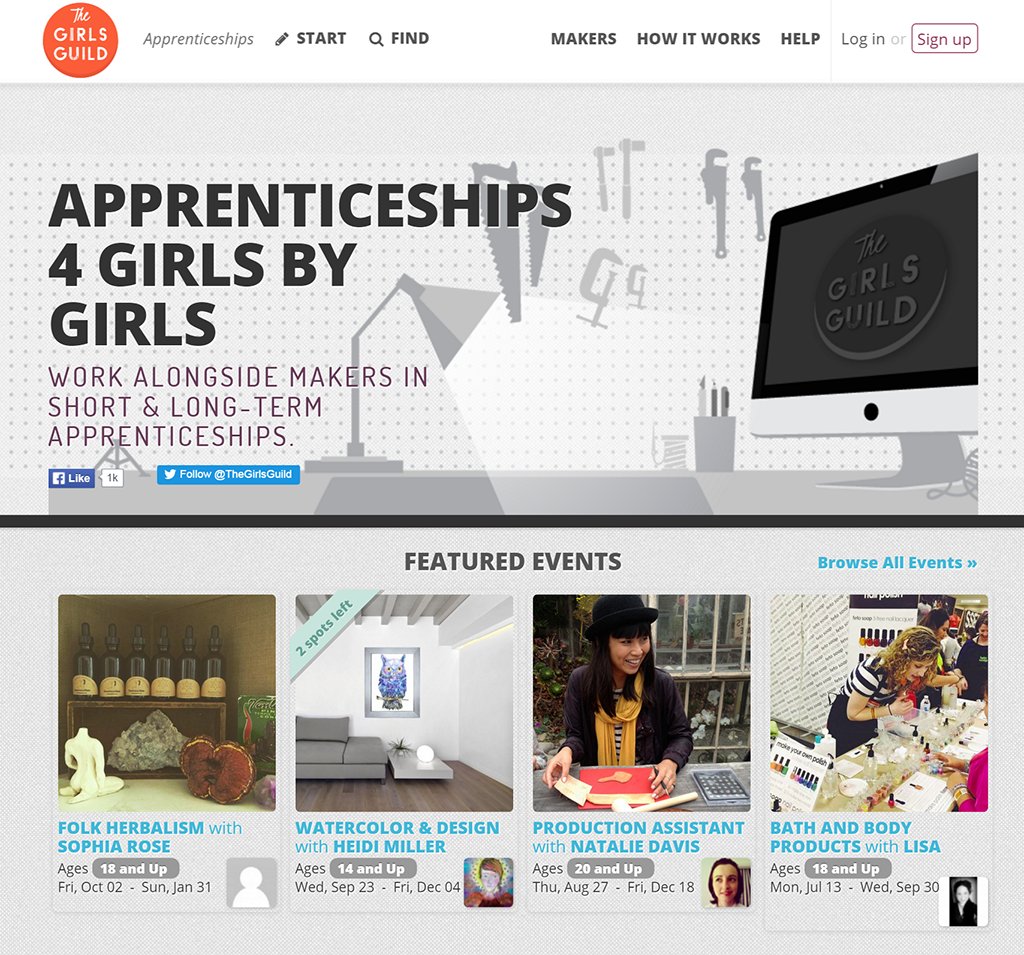

AC4D student project The Girls Guild: connects girls to work alongside makers in short and long-term apprenticeships.

DP: How many students did you have at first?

JK: Nine students. Nine students who would take a chance on an unaccredited, untested, brand new program. Good for them. And good for us, too. They’ve gone on to do tremendous things. I’m very pleased.

DP: You’ve got this great building. It’s a renovated house in East Austin. Has this always been the home?

JK: No. Just like everything, it evolved dramatically. The first year we squatted in a venture accelerator that my buddy runs. He gave us free space, and we got in his way, ate all the food, used up the whiteboard markers, and overstayed our welcome. In year two, we rented a house that we found out later was zoned residential, and we shouldn’t have been in there in the first place. And then in the third year, we bought this house because it took about three years to convince myself that this was a real thing.

DP: The offering is a 10-month experience?

JK: It’s 32 weeks, four quarters— a one-year program. We also offer some other training and one-day workshops. But the primary offering is that one-year program.

We typically have between five and 15 students. We have nine faculty members. The classes are very small and students get a good amount of face time with faculty. The faculty are all working professionals—not lifetime academics, but practitioners.

It’s a very close community. The alumni stay in touch, they come to the events, they support each other, they act as advocates. If a student is starting a company, they’ll network for them. If they’re trying to get a job at a company, they’ll help them get that job.

DP: There is a really remarkable energy around the AC4D community. I know a number of people who have been through the program, and it’s very authentic. People who go through that program are believers, and absolute advocates. That’s a cool thing to see.

JK: They’re good recruiters, as well.

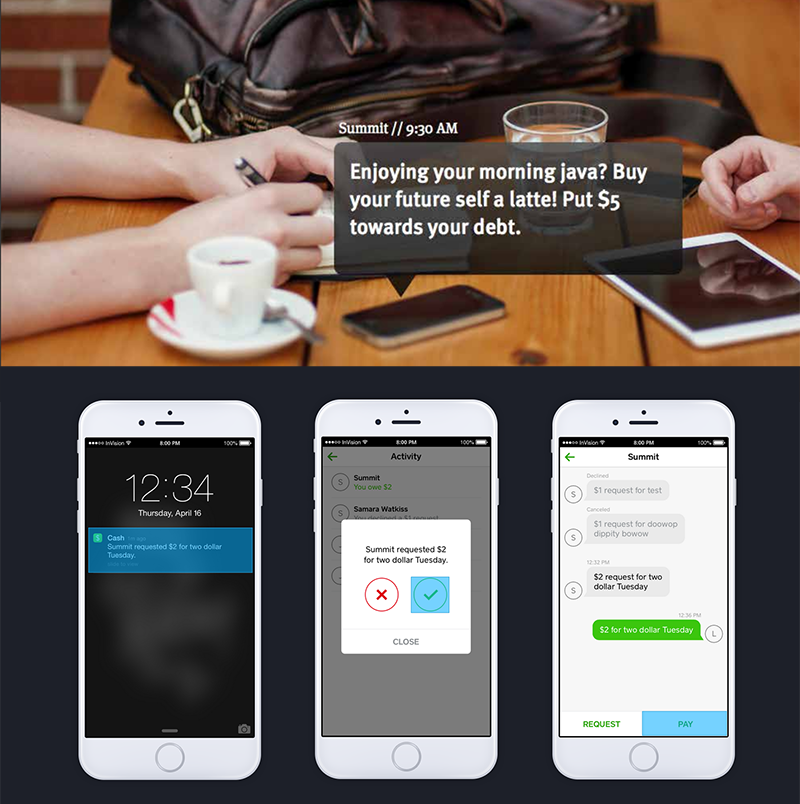

AC4D student project Summit: pay off your debt in daily small bits, and watch your balance disappear.

DP: Where do the students come from? Are they designers before they come here?

JK: The profile is typically a 28 to 32-year-old, somewhere in there. They’ve done something professional, but rarely is it design. I think we’ve probably had three designers. Often they are in business, maybe a business analyst, or in marketing, or engineering. We had one student who was in finance, and another was an artist. Just sort of a weird, eclectic mix. The continuity of all of them is they want to learn how to use making things as a way of driving themselves. As a way of seeing the world. As a way of changing the world. The value promise of gaining autonomy through making really resonates. Because I think a lot of people are design tourists. They look at the blogs, they read the sites, and go to MOMA and say, “I wish I could make stuff.”

DP: The packaging of the experience at AC4D is really appealing to someone in that part of their life and career. We’re talking about somebody who is making a pivot of some sort, retooling themselves. And the notion of taking two, three more years off, and disposing thousands of dollars’ worth of debt through a traditional academic experience is probably prohibitive.

JK: It is. The money is worth pointing out, too. The programs that some of my colleagues run are extraordinarily expensive. They’re very, very good, but I don’t know how you cost justify $100,000 in debt.

Our program is $15,000, and I actually think that’s too much, but that’s what we need to operate the business.

DP: It’s sharp contrast to virtually any other offering out there.

JK: I think so. And I think it’s well worth it. I don’t mean to belittle any other program’s value, including our own. But $100,000 is a ridiculous amount of money, and even $60,000 is a ridiculous amount of money. And by charging that they’re asserting that what it takes in order to take control of your life.

DP: Let’s talk about collaboration as a way of working as a designer in our time, as opposed to another era where it might have been more of an individual experience. How does a student going through the program at AC4D experience collaboration? Is that an explicit part of the experience? Or does it just happen by accident?

JK: The whole experience is group work, for lack of a better word. The students go through a 24-week project, which is focused on a social or humanitarian upside, and they start companies. It’s not really a project as much as it is creating a product, creating a business around it, and then creating a marketing plan for it. And they’re doing that collaboratively. All of the projects, for the most part, are collaborations with just a couple of exceptions.

But, I have found that there are core skills—scenario building, wire framing, service design, textual research—where they need to know how to do it themselves. That way they can pop out the other end of the program and be able to say, “I can do this,” and say it with authority.

DP: A nuance that gets left behind when we talk about the skill of collaboration is the ability to step into a team that you didn’t get to choose.

JK: And that you don’t particularly always like.

DP: Exactly. One that includes probably some other designers, but almost always some non-designers. And pretty much everyone else on the team has another, and usually conflicting, point of view.

There’s a whole set of skills around working in that kind of environment, and that is absolutely the environment that our designers are faced with. The answer can’t be, “This doesn’t work for me. I want to go off and do this by myself.”

JK: I’ve found that there’s an interesting tension between working in a group and making things. One of the most important parts of doing that, though, is being good at making things. Because if it takes you all of your heart and soul and blood and tears to make something that is of any kind of quality, of course you want to protect it. It becomes precious.

But if making things is second nature to you, then it’s like, “Okay, I made it. Now let’s talk about it. Does it move us in the right direction? Okay, it doesn’t? Well, fine. Let’s make something else.” There’s an impermanence to it.

DP: That’s a very modern idea. So many people come to design because of their love of making and crafting and polishing. The pride, and the praise that you get out of it. I think it gets back to a very poignant conversation around the word “design”. Maybe we’re just using the wrong word.

JK: It might just be life, right? I say to my students, let’s not call it “design” for a second. We’re giving them a series of methods of making things in order for them to take control of their lives, and if they want to apply them in business, apply them in business. If they want to apply them in their marriage, do that. But now they have a new vocabulary.

AC4D students Sophie Kwok and Meg McLaughlin's project: Love Intently helps users create stronger relationships.

DP: Can you give us examples of the types of projects that have come out of AC4D, or even just types of concepts that are coming out of the program?

JK: I’ll give you an example, one that I’m real proud of, but I’m afraid I won’t do justice. Sophie just launched her first public beta of Openly, which is a service that you and your partner sign up for, and you enter in things that your partner likes and you set reminders. Then the app will give you nudges like, “Your partner responds to touch. Have you given her a hug today?” “Your partner responds to humor. Did you tell him a joke today?” It might even be something like, “Hey, it’s 5:00. Probably you’re coming home from work and you’re exhausted. If you pick up something on the way, that’d surprise her.” Very simple nudges like that. It’s formulated around this idea of love languages, which marriage counselors use, that Sophie learned about in her research. It talks about how everybody is a precious snowflake, but there are patterns to how people respond to each other.

DP: Algorithms.

JK: Exactly. So she came up with the idea, and usually in design school, that’s where you end. But she’s building it. She put together the product. She set up a business story around it. She put together a landing page to sign people up.

DP: And how does she, or how do you, frame that in the context of social good, or human good? What’s the spin on that? It’s somewhat obvious, but it’s not a typical social impact design.

JK: It’s not. It’s about harmony in relationships and understanding a sort of newness of the types of relationships we have, rather than a man/woman marriage with everyone living happily ever after under one roof. Now we have partners come and go, and all sorts of diversity, and people break up and get divorced, and there’s a lot of stress around relationships. So for Sophie, she sees it as being about wellness. She talks about it as a health issue, in many respects.

DP: That’s great. I think we’re in a moment where that type of thought, and framing, and reframing, and recontextualizing the whole notion of social impact design is required. You know, I think it’s gotten...I know this is a provocative term...it’s gotten kind of ghettoized.

JK: You mean like it has to be in Africa, and it has to be a cook stove, and clean drinking water or it doesn’t count.

DP: Exactly! Our work at IBM is absolutely impacting society. And yet, we don’t think of it as social impact. So how do we rebuild the frame of what design is in terms of what social impact really means?

JK: It’s a textured conversation. Consistently for me, it comes to back to ethics. Do you have an ethic for your work? Or are you just a “hands for hire”? When you talk to people who study ethics, like hardcore philosophers, ethics are not just subjective. It’s not like anything goes, as long as you’re consistent. There’s actually good grounding criteria for what makes ethics, ethics. And I think a big part of that is establishing your personal values, and then understanding how they relate to the world around you.

DP: Talk to us about the writing that you’ve done thus far, and some of the ideas that you’ve addressed.

JK: This idea of social and humanitarian impact is one. With the school I published a book called Wicked Problems, which we gave away for free. It’s our curriculum in a book. That was an interesting project.

I also wrote a book that was published by Oxford, on design synthesis and interpretation. It’s called Exposing the Magic of Design. In my opinion, it’s the best thing that I’ve written, but it didn’t sell very well.

My most recent book with Harvard is Well-Designed. It’s a business book that explores the connection between interaction design and product management—what it means to be in charge of, and responsible for, the success of a product or a company.

If you look at a lot of digital companies, a new role has emerged: “product manager”. It’s typically a role that has no mandated authority. You’re not in charge of things. You don’t get to fire people. You typically have no budget. Yet you’re in charge of getting people to build the right product at the right time, and ship it. That means that you have a series of skills that are related to things like product vision, product road mapping, working inter-disciplinarily with people. A huge part of product management is spinning a story of how great the world would be if this new product existed. And getting people to believe that story, so they follow you, so they buy the product.

DP: In a sense, it’s soft stuff, it’s human stuff. But it’s absolutely essential.

JK: I think that it makes sense that it’s soft and fuzzy, because value is often soft and fuzzy. And really, a product manager is all about defining and delivering on value. Probably the most important thing they do is identifying a value promise, or a value proposition.

DP: So what’s next as far as your writing output?

JK: I’ve been thinking an awful lot about creativity in organizations. And how it does or doesn’t work, and what are the right or wrong environmental things that have to be there.

DP: What do you mean by organizations? Are these established companies, big corporations, or small startups?

JK: All of the above, because I think everybody is struggling with the power of creativity. They understand why they want it and need it. But when they start to bring it into their startup, consultancy, or giant company, it’s a mess. I think that there is a method to the madness that many designers have intuitively. But now, creativity is not ours anymore. We don’t get to claim that we are creative people in the world. There’s an expectation that everybody at the company is creative.

But everybody can’t, suddenly, become creative. If they’re asked to be, and they aren’t, chances are they’re going to be very uncomfortable with processes that come with being creative. For example, there’s no right answer in a creative process. And I think a lot of people who are analytical are looking to be told the right answer, or looking to develop the right answer.

DP: If you tell them that it doesn’t exist, that’s a very, very uncomfortable.

JK: It’s very uncomfortable. Another example is critique. An accountant is not used to a public forum critique of their work.

DP: Another is starting the problem solving process with an understanding of humans. That’s deeply uncomfortable for many people.

JK: It is fundamental, and it’s the one that is most bemusing to me, because it’s about interactions with people. Just people. The other concerns I can understand. In critique, everybody’s looking at you. The idea of a right answer versus a wrong answer has been ingrained in you since you were four years old. But, “I’m uncomfortable talking to people,” has always just been kind of funny to me.

DP: There’s a lot of change in our world right now, and a lot of unknowns about what’s around the next corner. How do designers fit into the picture in the next few years? How are we relevant in this reality?

JK: I struggle with that a lot. I’m sort of tired of designers. And I’m not sure entirely what that means. But I think, maybe, the world is ready for design to be a liberal art, or be ubiquitous, where everybody can do this stuff. I don’t think that means designers go away. I think they become specialists. Maybe we can actually start to see what it’s like if children learn design alongside everything else in their curriculum. What happens when they pop out the other end of that story?

DP: Democratization.

JK: Yeah, it’s the democratization of these skills...I’m not unique in championing that idea, but I wonder if now it’s ready for it to have its day in the sun. There’s so much momentum around design, around watching a TED Talk about design, going to design conferences. We have, in many ways, arrived. Designers can bill at $250 and $300 an hour. Okay, cool, check that box. Now maybe we can do all this other stuff we want to do, like democratizing.

DP: I’m with you.

JK: Or maybe we can’t. Maybe we just keep making shit. I don’t know.