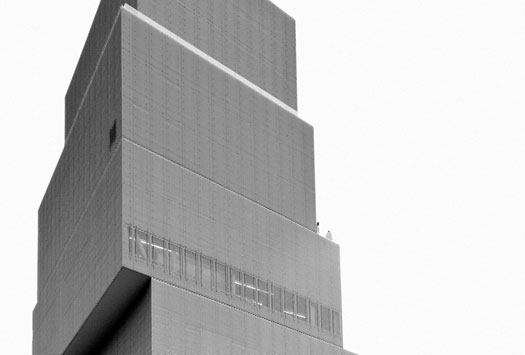

Sanaa, The New Museum, New York, New York, 2007. Photo by Blip Studio

While doing some research recently, I found myself reading Denise Scott Brown’s “Room at the Top? Sexism and the Star System in Architecture,” an essay written in the 1970s as a response to the routine discrimination to which she was subjected following her marriage to and partnership with Robert Venturi. Scott Brown didn’t publish the article at the time, fearing professional retribution, but circulated it among friends and colleagues. In the years since, acknowledgment of her work has remained sporadic and grudging. Most famously, in 1991, the Pritzker Prize was granted to Venturi alone, just the kind of “petty apartheid” of which she had written.

Scott Brown’s essay became topical a couple of weeks ago, with the selection of Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa, principals of the Japanese firm Sanaa, as winners of this year’s Pritzker Prize. Sejima becomes only the second female recipient of the prize (Zaha Hadid won in 2004), and the choice of a firm reflects what has long been standard practice in the profession: collaboration between partners of equal stature. “It is virtually impossible to untangle which individual is responsible for what aspect of a particular project,” reads the Pritzker citation. (The same might have been said about Scott Brown and Venturi.) Previously, only Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron, in 2001, had been awarded as partners.

As it is, my experience of Sanaa’s work is limited to the New Museum, here in New York. It’s a well-constructed stack of boxes with a memorable staggered profile and a dour metal façade that, depending on your perspective, is either an appropriate deference to the skeeziness of its Bowery neighbors or a too-knowing deference to the skeeziness of its Bowery neighbors. The galleries are cubic and minimal and somewhat claustrophobic. Public spaces, especially the terrace overlook, are nice. Circulation is bad. Overall, it’s an impressive project, given the constraints imposed on any new work of architecture in New York.

Sanaa’s portfolio outside of this city is not particularly extensive, but it’s distinguished and growing. In Japan, they’ve built several houses and a pair of museums. There’s a swoopy learning center in Lausanne, a cubic academic building in Essen, an extension of the Louvre in Lens (under construction), and a theater in the Netherlands. They’ve built a glass pavilion for the Toledo Art Museum, and another for the Serpentine in London. There’s a formal consistency to this work. Mostly it’s white, with a lot of clear glass. Whether this lends it a certain ascetic austerity or makes it clinically severe is, again, a matter of taste. “They explore like few others the phenomenal properties of continuous space, lightness, transparency and materiality to create a subtle synthesis,” reads the Pritzker citation. “Sejima and Nishizawa’s architecture stands in direct contrast with the bombastic and rhetorical. Instead, they seek the essential qualities of architecture that result in a much appreciated straightforwardness, economy of means and restraint in their work.”

The ethereal properties of Sanaa’s catalog — I’m always leery when Asian designers are celebrated for their ability to conjure the phenomenal, but here the aesthetic asks for it — brings to mind another point made by Scott Brown in “Room at the Top”; in that essay she attributed male dominance in the profession to the “unmeasurable” nature of architecture, to the fact that its essential qualities are in part artistic and therefore “ill-defined and undefinable.” In the face of that subjectivity, she wrote, it’s natural to seek out a “guru” figure, an authority (necessarily male) who might provide direction and clarity to the wayward seeker. Times have changed since Scott Brown wrote that essay, but not that much. Architecture still demands its gurus — we call them “starchitects” now — and they can, on occasion, even be female. The Pritzker is devoted to nothing so much as anointing the latest.

Is that a worthwhile pursuit? Does the profession require the publicity attendant with such prizes? Does the success of a few standard-bearers trickle down to the rest of the field, in the guise of added exposure and a generally elevated status for design? Are the benefits worth the costs, the most glaring being an entrenchment of the division between a group of jet-setting international stars and those who practice with less fanfare, between the gurus and non-gurus? It’s telling that so many young architects I know have such ambivalent feelings about the Pritzker. They’re keen to handicap the candidates and debate the merits of the winners, but they’re also quick to deride the prize, much as serious cineastes dismiss the Oscars. Of course, they’d all love to have the Pritzker medal hanging around their necks. Everyone, I suppose, wants to be a guru.

While doing some research recently, I found myself reading Denise Scott Brown’s “Room at the Top? Sexism and the Star System in Architecture,” an essay written in the 1970s as a response to the routine discrimination to which she was subjected following her marriage to and partnership with Robert Venturi. Scott Brown didn’t publish the article at the time, fearing professional retribution, but circulated it among friends and colleagues. In the years since, acknowledgment of her work has remained sporadic and grudging. Most famously, in 1991, the Pritzker Prize was granted to Venturi alone, just the kind of “petty apartheid” of which she had written.

Scott Brown’s essay became topical a couple of weeks ago, with the selection of Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa, principals of the Japanese firm Sanaa, as winners of this year’s Pritzker Prize. Sejima becomes only the second female recipient of the prize (Zaha Hadid won in 2004), and the choice of a firm reflects what has long been standard practice in the profession: collaboration between partners of equal stature. “It is virtually impossible to untangle which individual is responsible for what aspect of a particular project,” reads the Pritzker citation. (The same might have been said about Scott Brown and Venturi.) Previously, only Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron, in 2001, had been awarded as partners.

The selection of Sanaa has generally and deservedly been received with enthusiasm by the architectural press, though one might ask if they are really any more deserving than, say, MVRDV or DS + R (both with female partners), Steven Holl, Peter Eisenman, or the deceased Enric Miralles. Wouldn't it be nice to see Lebbeus Woods take the prize? That's what makes horse racing. There's always next year.

As it is, my experience of Sanaa’s work is limited to the New Museum, here in New York. It’s a well-constructed stack of boxes with a memorable staggered profile and a dour metal façade that, depending on your perspective, is either an appropriate deference to the skeeziness of its Bowery neighbors or a too-knowing deference to the skeeziness of its Bowery neighbors. The galleries are cubic and minimal and somewhat claustrophobic. Public spaces, especially the terrace overlook, are nice. Circulation is bad. Overall, it’s an impressive project, given the constraints imposed on any new work of architecture in New York.

Sanaa’s portfolio outside of this city is not particularly extensive, but it’s distinguished and growing. In Japan, they’ve built several houses and a pair of museums. There’s a swoopy learning center in Lausanne, a cubic academic building in Essen, an extension of the Louvre in Lens (under construction), and a theater in the Netherlands. They’ve built a glass pavilion for the Toledo Art Museum, and another for the Serpentine in London. There’s a formal consistency to this work. Mostly it’s white, with a lot of clear glass. Whether this lends it a certain ascetic austerity or makes it clinically severe is, again, a matter of taste. “They explore like few others the phenomenal properties of continuous space, lightness, transparency and materiality to create a subtle synthesis,” reads the Pritzker citation. “Sejima and Nishizawa’s architecture stands in direct contrast with the bombastic and rhetorical. Instead, they seek the essential qualities of architecture that result in a much appreciated straightforwardness, economy of means and restraint in their work.”

The ethereal properties of Sanaa’s catalog — I’m always leery when Asian designers are celebrated for their ability to conjure the phenomenal, but here the aesthetic asks for it — brings to mind another point made by Scott Brown in “Room at the Top”; in that essay she attributed male dominance in the profession to the “unmeasurable” nature of architecture, to the fact that its essential qualities are in part artistic and therefore “ill-defined and undefinable.” In the face of that subjectivity, she wrote, it’s natural to seek out a “guru” figure, an authority (necessarily male) who might provide direction and clarity to the wayward seeker. Times have changed since Scott Brown wrote that essay, but not that much. Architecture still demands its gurus — we call them “starchitects” now — and they can, on occasion, even be female. The Pritzker is devoted to nothing so much as anointing the latest.

Is that a worthwhile pursuit? Does the profession require the publicity attendant with such prizes? Does the success of a few standard-bearers trickle down to the rest of the field, in the guise of added exposure and a generally elevated status for design? Are the benefits worth the costs, the most glaring being an entrenchment of the division between a group of jet-setting international stars and those who practice with less fanfare, between the gurus and non-gurus? It’s telling that so many young architects I know have such ambivalent feelings about the Pritzker. They’re keen to handicap the candidates and debate the merits of the winners, but they’re also quick to deride the prize, much as serious cineastes dismiss the Oscars. Of course, they’d all love to have the Pritzker medal hanging around their necks. Everyone, I suppose, wants to be a guru.