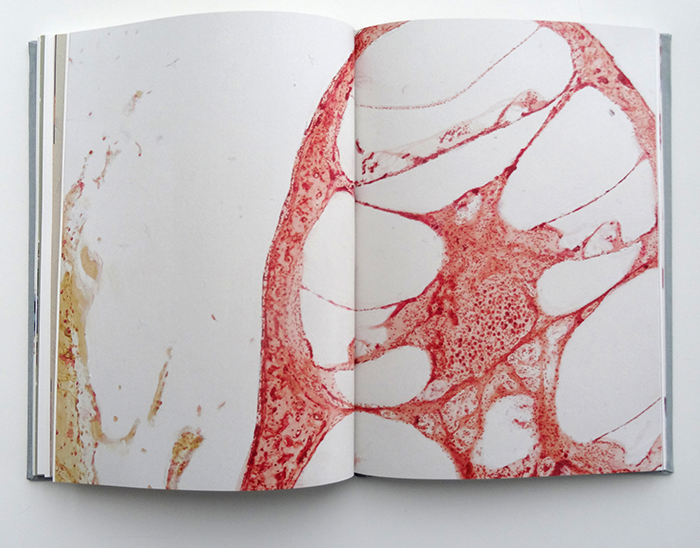

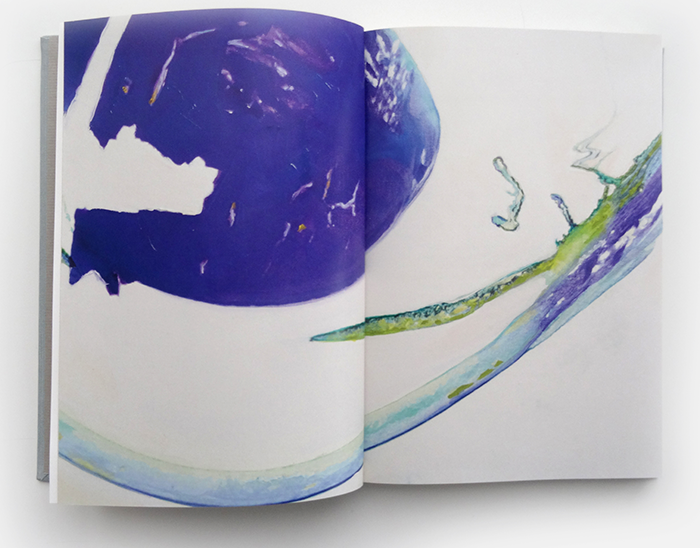

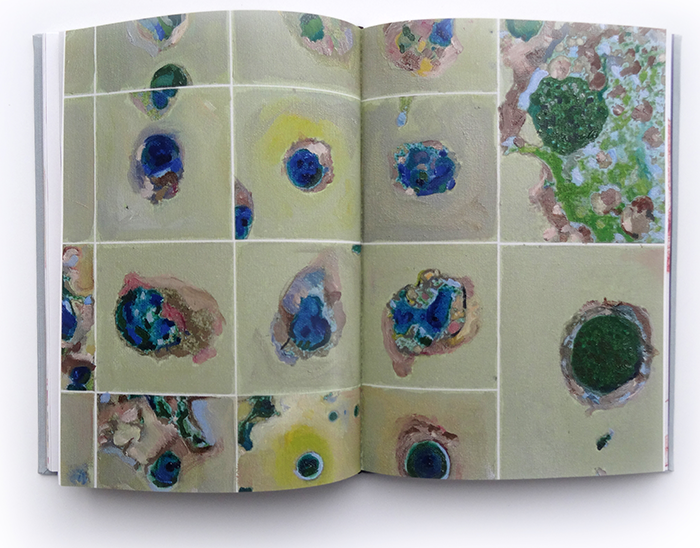

This, and the paintings below, by Jessica Helfand, as they appear in her book Design: The Invention of Desire

Designers are jinxed. They are victims of a spell cast on them in the middle of the last century. This curse is the work of three people: Eliot Noyes, the brilliant Cold War strategist, architect, and industrial designer who coined the term Good Design; Edgar Kaufmann Jr., who launched an aggressive media campaign to promote MoMA’s Good Design exhibitions; and Thomas Watson Jr., the celebrated IBM president who came up with the Good Design is Good Business slogan.

Ever since, designers have been laboring under the assumption that their work must be “good.” Or that they must serve “the public good.” Or that they must cultivate “good” clients. How pathetic. Other creative professionals would be mortified to be subjected to standards of goodness or, God forbid, to be described as being merely good. Good architects? Good photographers? Good writers? Please. These people want to be great.

At long last, someone from within the ranks of the “Good Designers” is nudging good design out of its comfort zone. With her latest book, The Invention of Desire, Jessica Helfand is questioning the reasons why it is so difficult for designers to join the human race. Courageously, she exposes the kind of posturing she and her colleagues have embraced in pursuit of goodness.

In a series of short essays with titles like "Compassion," "Melancholy," or "Solitude," she examines the profession, proposing ways of defining design excellence in terms of right or wrong rather than good and bad. “[Our] job it is to steer the conversation toward something as basic, as critical—and as profoundly human—as consequence,” she writes. On the subject of making things better (another Good Design obsession) she asserts “We would all of us do well to remember that design, no matter how cleverly conceived, or subversive, or disruptive, is never going to change [our impending mortality].

Early in her argument, she identifies what, in my opinion, drives most designers to seek virtuosity rather than virtue: the fact that design is “an industry that does not require certification,” You can practice design without a license, “which makes everyone a designer,” she adds. “Or, for that matter, no one.”

Like artists, who do not need diplomas, designers depend on the appreciation of others to justify their raison d’être. However, unlike artists, they lack the Salon-des-Refusés narrative, the rejection-by-jury redemption stories. There is no equivalent of Edouard Manet in the design world, no Déjeuner sur l’herbe example to edify or inspire. Case in point, Paul Rand’s famous Eye-Bee-M poster. The fact that it was originally refused by the client is seldom mentioned in graphic design history books, and this critical detail has been expurgated from the official website of IBM where the once maligned poster is nonetheless prominently displayed.

Helfand bemoans the inability of designers to embrace failure as part of the process—or as part of its potential outcome. “Once unmoored from our imaginations, the things we so enthusiastically produce embark on their own tricky odysseys, whereupon they are invariably poised to gain their own momentum, to traffic in their own often unprecedented vulnerabilities.” She believes that “accepting the limitations of what design can’t do” is a step in the right direction.

Written in engaging prose, The Invention of Desire is a collection of musings triggered by some of our most current design foibles: our questionable reliance on brilliance, our infatuation with innovation, our dependency on readily available pictures, our insistence on sharing viewpoints, and our epic struggle with guilt. Missing on this list is the reluctance of American design professionals to tackle tough political issues. Helfand doesn’t mention the fact that a less complacent attitude toward the capitalist system might help her colleagues assume the visceral approach to problem solving that she fervently advocates. Wisely perhaps, she shuns this potential minefield and instead focuses her wrath on rampant feel-good practices. “We can’t just keep feeling good because we recycle, or because we print with soy-based inks, or because we only listen to music we pay for,” she gripes.

As far as she is concerned, the best way for designers to escape “the vicissitudes of style and the burden of cool” is to change the scale of their inquiry. While Big Data is a revolution we can’t ignore, she suggests we simultaneously turn our glance inward and connect with biological truths at the micro level. To visualize what this other paradigm shift into the depths of our being looks like, she opens each chapter with a detailed view of cell organizations in human tissues.

Abstract forms at first glance, these strangely evocative visuals turn out to be painted on canvas, with barely visible brushstrokes as intricate as tangles of neurons or as wispy as bundles of teased nerves. These handsome paintings, the work of Helfand over the last couple of years, are doubtlessly examples of Good Design, yet the complex organic structures they represent remain alarmingly incomprehensible.

A sobering thought! It is one of many in this provocative compendium of smart observations by someone who is fed up with our besotted attitude toward technology and believes it’s time we call into question the dominant design narratives.

THE INVENTION OF DESIRE is published by Yale University Press / An Observer Edition

224 pages, illustrated, designed by Jessica Helfand and Sara Jamshidi