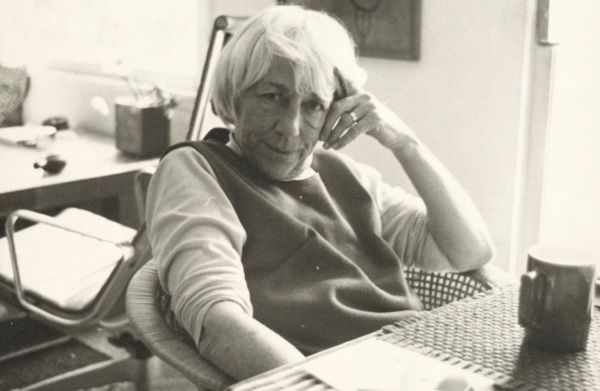

Reyner Banham wasn't cowed by many, but even he was nervous about meeting Esther McCoy. When he arrived in Los Angeles in 1965, it was five years after the publication of McCoy's Five California Architects had given the contemporary scene a backstory, highlighting the careers of Greene & Greene, Irving Gill, Bernard Maybeck and R.M. Schindler. As Banham wrote, "Until about 1960, the rest of the world had practically no idea at all about architecture in California... Then this extraordinary book came out in 1960, and – suddenly – California architecture had heroes, history, and character."

He continued, in a 1984 tribute, "The Founding Mother," published in California Magazine:

There was a clarity, a plainspoken directness about her writing that, to me, was engaging as well as informative, but, later, I discovered that her plain speaking has caused some concern among our mutual friends. I myself have a bit of a reputation for saying it like it is – "acerbic" they call both of us – and the expectation seemed to be that we would try to shred one another conversationally when we met.Oh, to be a fly on the wall... But of course they did not shred each other. Instead, Banham found, "she really doesn't have a malicious bone in her body. She speaks as she finds, with sympathy and honesty, and relevantly to the matter at hand."

Which is the best definition of a good critic I have read in some time. I'm embarassed to admit that until last month, I had only read McCoy instrumentally, when I was researching Gill or Schindler, Neutra or the Eameses. A new collection of McCoy's writings, Piecing Together Los Angeles, has just been published, and it gives all laggards an opportunty to plunge in. As I wrote in my review of the book for Architectural Record:

Affection isn’t a word often used to describe architecture criticism, but that’s the ruling emotion of Piecing Together Los Angeles, the first collection of the writings of California historian and critic Esther McCoy (1904-89). There’s McCoy’s affection for Los Angeles superstars like Charles Eames, Pierre Koenig and John Lautner when they were young and needed books like McCoy’s Five California Architects (1960) to give their work a backstory — and when they were old, and the world needed a reminder of their talents. (On Lautner: “Instead of repose, his houses are thorny with ideas, ideas that wake up the eye and astonish the mind.” On Ray Eames: “She had one of those minds that feasted on facts. Along with this was a sensibility that could transform facts into art.”) Reyner Banham called McCoy “the founding mother” and said, “She has the gift of friendship...and is profoundly concerned about people... and that is one of the special strengths she brings to her architectural writing.” This book, which collects McCoy’s never-finished memoirs, essays on three generations of California architects, fiction, and retrospective essays from the 1980s, is the product of editor Susan Morgan’s affection for McCoy’s whole project. The culmination may be her contribution to Blueprints for Modern Living, the catalog for the Museum of Contemporary Art’s 1989 Case Study exhibition, published two months before her death.I urge you all to buy it and read it, for it is a pleasure. Susan Morgan wrote about her own process for T last fall, and about the house of another founding mother, Anne Tyng, this spring. Gabrielle Esperdy also has interesting obsrevations about McCoy and Banham here.

I also wanted to blog about the book here because, as it happens, Esther McCoy had very interesting things to say about two topics of my preoccupations: Ray Eames and architectural satire.

Ray Eames at home, photographed by LIFE (via Daily Icon)

When I reviewed Marilyn Neuhart's monumental The Story of Eames Furniture, I talked about the vexed nature of Neuhart's attitude toward Ray, and the ongoing question of the nature of Ray's talent. Some took offense at my suggestion that Ray might today have been a stylist. But McCoy, who was a personal friend of Ray Eames, offers a beautiful remembrance of her as "a lover of small packages." I think she comes closest to defining Ray in a way we outsiders can understand.

The house was a framework for the display of rich objects; exposed steel columns, industrial steel roofing as in industry, and factory sash. It was a showcase for what Robert Venturi called "the good Victorian clutter." To Charles Moore, the house "filled in the Spartan framework with rich content." But it was Ray who "single-handedly brought about a return to richness, the joy of the miniature object in the modern framework."Second, McCoy wrote fiction, including a terrific short story, published in the New Yorker in 1948, called "The Important House." I am trying to get the New Yorker to unlock it from the archives, but here is the link for subscribers. As I write in my review,

The story encapsulates the tensions Alice T. Friedman described in Women and the Making of the Modern House, between the female client and the male architect, a slip-covered sofa and a metal tube cot. I wanted to cry for Mrs. Blakeley. McCoy, despite being on the side of the architects, seems never to have lost her sense of the house (and it is for its houses that McCoy thought California would be known) as a place in which to live.I have thought often about writing fiction about the topic of living in modern houses, even a book structured as the dark side of shelter magazine prose. I tried my hand at it here, in a fragment titled, revealingly, "Wives of the Architects." It was a wonderful surprise to find I had a mother in this idea, too.