Exterior of former artillery shed adapted by Donald Judd to house his 100 works milled in aluminum, Marfa, Texas

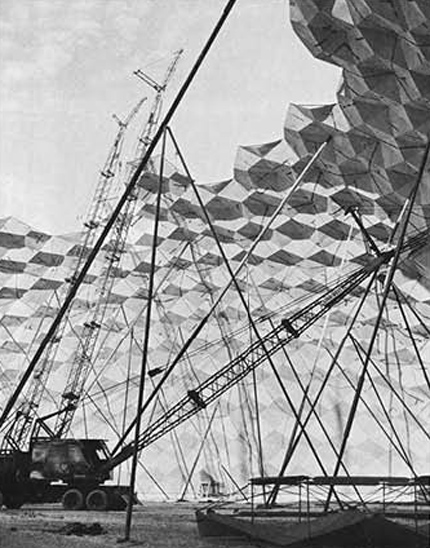

I first went to Marfa, Texas, at the end of November of 1992. At the time, I was an editor of Architectural Record magazine and I was doing a story on Donald Judd’s architecture. This article had been a subject of considerable debate among my colleagues: Judd was not a licensed architect, and some of my colleagues thought that a professional magazine would be sending a troubling message to its readers if it gave such a prominent platform to someone who wasn’t officially — and legally — part of the profession. I’d like to think that the impasse was finally broken when I showed photographs of the artillery sheds Judd designed at Chinati, his museum in Marfa, and declared, perhaps even dramatically, that this was architecture and did credentials really matter? My point was made and the pitch for the story approved.

I’ve thought about that episode — and, more specifically, the proposition that architecture is made not just by architects — many times over the years. The corollary — the question of what is and isn’t architecture — pervades Judd’s entire career. While Judd is known for emphatic pronouncements that broker little doubt, it actually takes some digging to get at what he specifically articulates architecture is, or isn’t, and how it exists, or doesn’t, apart from art. Not surprisingly, the difficulty of untangling the strands of his views on art and architecture says a lot about his work in both disciplines.

Judd worked as an art critic in his early years in New York as he established himself as an artist. From 1959 until the mid-1960s, his art criticism was his primary, if not only, source of income. At some point during that period, he strayed into writing about architecture, much in the way that he strayed into making architecture later on — without fanfare, assuming that there were no defined borders between the disciplines and it was somehow inevitable for him to expand his reach. It was only much later, in 1990, well after he had begun making architecture, that he formally acknowledged it as its own territory — and one that was already conquered — by opening a separate office dedicated solely to architecture in Marfa.

But architecture had been on his mind for a long time. In 1947, when he was in the military in Korea, Judd was a construction foreman in the Army Corp of Engineers overseeing the assembly of prefabricated buildings. When I met him in Marfa in 1992, he talked about that

period with a certain satisfaction. I asked him if he felt, upon returning from Korea to the U.S., that he would have to choose between architecture and art. He replied: “You had to do one or the other. One was a profession like a dentist or a doctor. The other was hopeless. So I picked the hopeless one.” He added, “One reason for not being an architect is that it’s a business. I didn’t think I could work with clients.”

Despite the seemingly definitive tone of that statement — “So I picked the hopeless one” — I believe that he never really wanted to make a choice between the two, and, clearly, from all evidence in Marfa, he never actually did. I think the idea that he had to choose between art and architecture was imposed on him. And Judd being Judd, it was an idea he would rebel against, first inwardly, and then later outwardly.

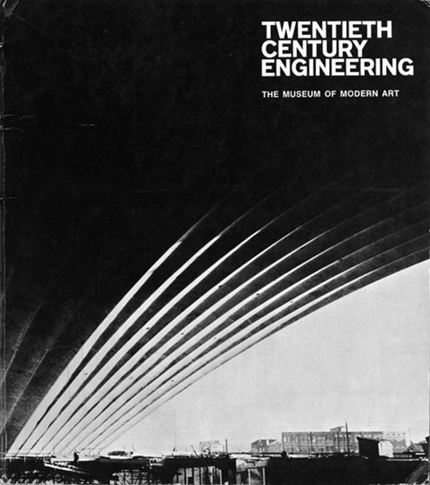

One of Judd's first writings to touch, at least obliquely, on what he thought architecture was and wasn't appeared in October 1964, when he wrote a review for Arts Magazine on “Twentieth Century Engineering,” an exhibition that had recently opened at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. And it came at a time when, coincidentally or not, he was beginning to make his first three-dimensional work.

In his introduction to the exhibition catalog, curator Arthur Drexler observed: “In the twentieth century the art of architecture has sought to emulate [engineering’s] rigorous efficiency and the boldness of its forms.” It is this theme — put most simply, the place where utility and beauty meet — that was particularly fertile for Judd.

Judd was obviously impressed by the images of dams, bridges, water towers, highways, refineries and grain silos in the show, pronouncing them “the bulk of the best visible things made in this century.”

Judd was obviously impressed by the images of dams, bridges, water towers, highways, refineries and grain silos in the show, pronouncing them “the bulk of the best visible things made in this century.”

Twentieth Century Engineering catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1964

He began his review by comparing such engineering works to the less publicly accessible disciplines of art and architecture. He remarked that “Art is small in size and not as plentiful; architecture is fairly rare,” and noticed that good engineering abounds yet doesn’t, for some reason, have the same standing as architecture.

As can be the case with Judd's writing, particularly his early efforts, some of the review's sentences are pared down to such an extreme that taken one at a time they seem painfully obvious — like this sentence: “Until lately art has been one thing and everything else something else.” Other sentences are completely nonsensical — like the next one: “These structures are art and so is everything made.” The rigid exclusion of anything Judd considered extraneous has long provoked a comparison between his writing and that of Ernest Hemingway, but these two examples show that Judd’s is characterized by both economy and understatement and economy and overstatement.

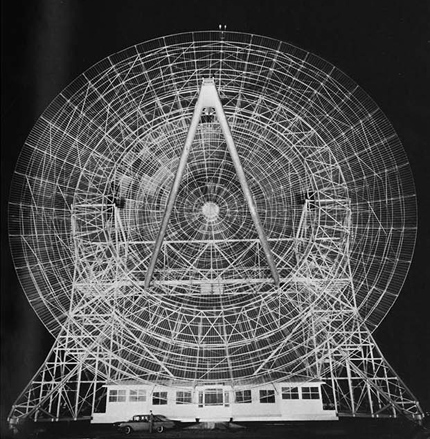

Radar telescope. Stanford California. 1963. Stanford Research Institute (Ray L. Leadabrand).

In all cases, the meaning in Judd’s writing comes from the amalgam of individual sentences — like the layering of paint or stacking of forms — and for that reason I will quote from the review at some length.

The excerpt begins:

Until lately art has been one thing and everything else something else. These structures are art and so is everything made. The distinctions have to be made within this assumption. The forms of art and of non-art have always been connected; their occurrences shouldn’t be separated as they have been. More or less, the separation is due to collecting and connoisseurship, from which art history developed. It is better to consider art and non-art one thing and make the distinctions ones of degree. Engineering forms are more general and less particular than the forms of the best art. They aren’t highly general though, as some well-designed utensils are. Simple geometric forms with little detail are usually both aesthetic and general. The few good buildings, ‘real architecture,’ are more specific than most of the engineering projects. But most buildings are far inferior to engineering projects, which with their definitive use and the supposed objectivity of their solutions, have been allowed a freedom and advancement not accorded to buildings and architecture. Buildings only have to have space; they are easy to construct. Commercialism dominates the engineers and architects, and the best knowledge isn’t used. Several of the buildings in this show are only models: Louis Kahn’s City Tower and office building by Clive Entwhistle. They are apparently feasible, but they are inventive and probably won’t be built for some time. None of the plain beauty of well-made things has ever gotten into New York’s housing projects, and little has occurred in the office buildings, which are mostly either like consumer junk…or are absolutely barren…

Judd goes on to say:

As the anonymity of the profession indicates, the society has an odd attitude toward the best projects built by engineers. They are considered fine for what they are but neither something to live in nor to have an office in. A moderate-looking building with a little gold and white trim is fit for habitation. The only art that is involved is an idea of elegance, which is thoroughly puerile. Even fairly well-designed things like some cars and buildings are too elegant, though genuinely so — most Skidmore, Owings and Merrill buildings, for example. The engineering structures prove that this elegance isn’t desirable. Architects are prone to elegance and are not especially imaginative. Much of engineering is better architecture than most architecture.

I’ve quoted this lengthy passage from his review for several reasons: partly, as I mentioned, to give a sense of his style of writing because, as with his artwork, the form is a good indication of the content. The absence of description or obvious stylistic embellishment creates an aesthetic so spare that it is, at times, almost aggressive. Here, the prolonged staccato of declarations belies a complexity of thought. His sentences are rational, lucid and reductive yet when they are assembled the overall effect is quite intricate. And it’s worth noting that his attempt to define “architecture” emerges only as he states his opposition to conventional ideas of art and engineering — definitions he rejects. What some people call engineering — Buckminster Fuller’s domes, for example — he calls architecture.

The other difficulty of untangling these passages, to my mind, is that in reading them one gets a sense of Judd trying to define the significance of the exhibition's work for himself. Clearly taken by the utilitarian beauty of the structures on view — similar to many such structures Judd had already seen in travels around the U.S. — he is in a sense fashioning his theory of architecture in front of our eyes. The beauty and the frustration of Judd’s writing is that its complexity and subtlety come from stringing so many simple declarative sentences together so that isolating one phrase as representative of the whole is nearly impossible and not necessarily advisable.

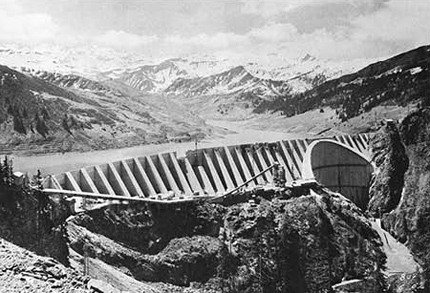

Roselend Dam. Doron de Beaufort River, France. 1961. Electricité de France; Coyne et Bellier.

Or is it? I understand that Judd did not appreciate editing. In fact, in the 1974 introduction to his anthology of complete writings, he recalled debating (and, it appears, often later rejecting) even small changes made by his editors at Arts Magazine. As a longtime editor, I can’t resist the urge to clarify and condense, however. So I decided to extract key phrases from the long passage I quoted and arrange them in a sequence — as if they are the axioms of a single theorem — to see if there’s an implied conclusion. To see if I could, in effect, get to the point more quickly.

Reordered, the main points to Judd’s argument are as follows:

– Architecture is fairly rare.

– All structures are art, though engineered forms are more general and less particular than the forms of the best art.

– Much of engineering is better architecture than most architecture.

– “Real architecture” is the few good buildings that are more specific than engineering projects.

– “Real architecture” is, therefore, the plain beauty of well-made things.

Of course, this is not a proof, though it is revealing that the process leads to one key phrase: “the plain beauty of well-made things.” With the benefit of hindsight, we can see that this phrase emerges as Judd’s central theory of architecture. It is this idea that he put into practice some five years after the review of “Twentieth Century Engineering." And because of the subtlety of the definition, it is perhaps more easily discerned in three dimensions rather than on the printed page.

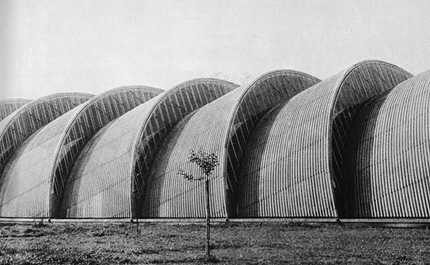

Gold-Zack Factory. Gossau, Switzerland. 1954. Heinz Hossdorf. Architect: Danzeisen & Voser

In November 1968, Judd purchased a cast-iron building at the corner of Spring and Mercer Streets in New York City in which to live and display art — his work and the work of others. In recounting the changes he made to the existing building, he wrote, some 20 years later:

I spent a great deal of time placing the art and a great deal designing the renovation in accordance.…The building finally contained more work of others than of mine, but I thought of many works in regard to it, primarily rejected because they were elaborate and took

too much space, and so went against the nature of the building. Other than leaving the building alone, then and now a highly positive act, my main inventions are the floors of the 5th and 3rd floors and the parallel planes of the identical ceiling and floor of the 4th floor. The baseboard of the 5th floor is the same oak as that of the floor, making the floor a shallow recessed plane. There is no baseboard, there is a gap between the walls and the floor of the 3rd floor, thus defining and separating the floor as a plane. These ideas were precedents for some small pieces and then for the 100 mill aluminum pieces in the Chinati Foundation. The renovation of the building and the permanent purpose of the building are precedents for the larger spaces in my place in Texas, Mansana de Chinati, for the Chinati Foundation, and will be for Ayala de Chinati.

It was in the Spring Street building that Judd refined and specified his ideas about architecture and, in doing so, uncovered ideas for his art. Judd renovated the building to accommodate specific works of art, and specific works of art were made in response to the renovation — the same approach he later used in Marfa. It wasn't just a question of the scale of works being possible in the relatively large new building, it was the specifics of the new construction — how walls met floors, for example, that were fundamental to his art.

There was a clear back and forth between media: art to architecture to art and back again. Strict categories eroded. In fact, Judd began to see his own work not just as an interconnected set of ideas but as an infinite variation on one set of ideas — his own.

Union Tank Car Company car rebuilding plant. Baton Rouge, Louisiana. 1959, R. Buckminster Fuller.

Many accomplished writers insist that they are not really sure what they are going to write until they actually start writing. The story, essay or article only really emerges in the making and then seems to take on a life of its own. This certainly seemed to be the case with Judd’s views on architecture — but in a slightly different way — as he shifted between considering the subject in writing and built form. His writing about architecture became much more pointed after he started making architecture.

His own work — in writing, in art, in architecture — inspired more work in writing, in art and in architecture. The consistent formal vocabulary — spare, decisive, reflective of an overall appreciation of the intrinsic beauty of simple elements — that runs through the various disciplines can be seen as a narrative thread of Judd’s career: his autobiography, in a sense.

In a 1983 essay about Abstract Expressionism, Judd discerned a common theme in the work of Jackson Pollock, Barnett Newman, Mark Rothko and Clyfford Still. Each of these artists, Judd wrote with admiration, made his work "a reality, not a picture of it.” To support this point, Judd quoted Jackson Pollock, who said, “The thing that interests me is that today painters do not have to go to a subject matter outside of themselves. Most modern painters work from a different source. They work from within.” Along these same lines, Judd approvingly quoted Barnett Newman, who said, in 1965, “The self, terrible and constant, is for me the subject of painting.”

It’s fairly conventional to say that most, if not all, of Judd’s work represents the accumulation of all of his experiences and is therefore autobiographical. It happens to be true, but not only in the way that everything we do is related overtly or subliminally to our histories. Judd’s work over time became increasingly the subject for future work. His architecture was for and about his art and in turn inspired new art. Like Newman and Pollock, Judd made his work his reality, and in addition he built his reality, quite literally, in Marfa.

If we agree with Judd that an artist makes what he is, then the installation of an artwork is an artist locating himself in the world at large. It is in this vein that Judd’s interest in architecture becomes paramount.

While Judd’s involvement in architecture became more overt over time, architecture was, in fact, embedded in his earliest artwork. Certainly Judd’s interest in making architecture grew in proportion to his disapproval of how his work was being installed by museums and his increasing disgust with the idea of museum architecture as art.

His interest, beginning in the early 1980s, in writing more specifically about architecture became a way of coalescing this viewpoint, and also a way to write about what he saw as the larger failures of contemporary culture. It became a way of talking about his art as it existed out in the world, while the renovation of various buildings in Marfa was his way of providing for his art — and the art of others he admired — in the long term.

In discussing the permanent installation of his work and the work of others, Judd wrote, “The main reason for this is to be able to live with the work and think about it, and also to see the work placed as it should be.” He added: “A bad location doesn’t ruin a good work but it tends to reduce understanding to information; you know it’s good but you can’t stand standing there long enough to find out why.”

Architecture is the place where his art lived, and Judd saw much, if not all, museum architecture as enemy territory. Of the museum boom of the early 1990s, he said: “The constant construction of museums of art, the worst of the worst, makes architecture for an artist a daily enemy.” In his view, this architecture exists for different reasons than art; it exists to represent status, money and power. As such, contemporary architecture is one big decoration, and how can art survive inside of decoration? Judd specifically disputed Frank Gehry and Peter Eisenman's idea of a “dialogue” between the art and architecture in museums. In fact, he called the supposed “dialogue” a violent conflict, which leads “only to aggression, only confusion, only failure.”

I don’t want my work to become part of the overstuffed fake elegance of the upper class; I don’t want it to sit on the grey middle class wall-to-wall carpet; I don’t want to join the lower class either, who want only social realism, as does everyone else. All of the references are obvious to most artists, who have worked their way through the clichés of the society. Why impose them on an art which has escaped them? Why can’t the space and the materials agree with the attitudes of the art?

Broadly speaking, one might say that for Judd, his art was about the self — his reality — and his architecture was about the work — his relation to the world at large. These are not separate entities, but overlapping ones. His art did not stop when it left the studio, and it is this recognition that drove his interest in making architecture — first in small ways in New York City, and then on a larger scale in Marfa. And just as he was fashioning his theories of architecture over the course of his review of the MoMA “Twentieth Century Engineering” exhibition, he was building his way into becoming a real architect — licensed or not — as he enacted his vision of a contemporary art museum.

On my first visit to Marfa, I was struck by the beds in many of the spaces where Judd's work is permanently installed. He told me the beds were there in case he got tired and wanted to rest without the interruption, in time or space, of going “home.” His explanation had a Judd-like pragmatism to it, but I can’t help thinking there was a larger message. Like many of the false dichotomies Judd rejected over his lifetime — thought versus feeling, philosophy versus practice, form versus content, mind versus body, rationality versus irrationality, abstract versus representational, particular versus general, objective versus subjective, simplicity versus complexity — the beds dismantled the division between his private and public selves and between his art and architecture. They represented one more barrier to willfully rupture. Judd’s ability to collapse the space between supposed poles is what gives his work its timeless appeal. And once all those distinctions are eradicated, the single trace line that remains, the overall constant in Judd’s art, architecture and even writing is, I believe, the plain beauty of well-made things.

This essay was adapted from a lecture delivered at the Chinati Foundation symposium, "The Writings of Donald Judd," held May 3-4, 2008. A published version of the proceedings is currently available. Please check the Chinati Foundation site for more information.

This essay was adapted from a lecture delivered at the Chinati Foundation symposium, "The Writings of Donald Judd," held May 3-4, 2008. A published version of the proceedings is currently available. Please check the Chinati Foundation site for more information.