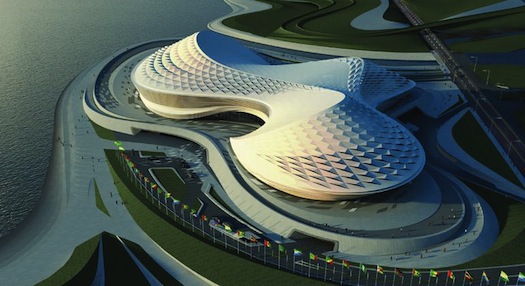

Zaha Hadid Architects, design for People's Conference Hall, Tripoli.

On March 25th, Zaha Hadid Architects made a quarter of its staff redundant, laying off more than 90 employees because of “unforeseen events in North Africa.” The reason was the democratic uprising in the Middle East, and specifically Libya, where Hadid’s new conference center outside of Tripoli had been “put on hold” while the beleaguered dictatorship’s post-meltdown kleptocracy returned its financial priorities to maintaining its grip on power.

But was this really a shift in Libya’s priorities, or rather the lifting of a veil that hid the various tools Qaddafi has employed to maintain such power for 41 years? One tool has clearly been the use of capital “A” architecture to project an image of cultural development.

Following the restoration of trade relations between the U.S. and Libya in 2006, Qaddafi has been busy leveraging his country’s emerging markets for direct, personal gain. He placed pressure on global oil companies to pay more than a billion dollars in fines emanating from the downing of Pan AM Flight 103 and other state-supported acts of terrorism. He regularly imposes — and pockets — fees from corporations seeking to gain access to these markets.

Meanwhile, Qaddafi has invested in branding to create the image of a “developed” country safe for investment. Green technology projects, as well as massive cultural centers for the “new Libya,” reflect a global trend to hire internationally recognized architects to transmit messages of progress through their works, effectively acting as cultural ambassadors.

Zaha Hadid’s architectural language is famously extravagant. When the discussion is complimentary, the word “iconic” is almost certain to pop up. Critics are more likely to describe her as excessive.

But the important question is not whether Hadid’s work looks like a squid or an octopus (as the city council of Elk Grove, California, recently debated about her new masterplan for that locale). It is whom architects are really serving — a community of residents, visitors and workers, or a community of investors — and why dictator states are the ones sponsoring so many of these projects?

Is the demand for architectural service so limited that we follow the money no matter whom it comes from? What role do architects have in changing this quid pro quo? In laying off a quarter of her staff after losing the Libyan project, Hadid seems to be saying, “Not much.” As an image-maker, she is also signaling, “Who cares?” A recent ruling by the Royal Institute of British Architects requiring all firms to pay their interns starting July 1 underscores a long history of heedlessness and apathy in the U.K. where Hadid’s office is. If architects must rely on dictators and free interns to stay afloat, they are practicing a failed business model.

The projects that get graced by capital “A” architects are intertwined with the capital required to build them. What is purchased is the commodity of cultural acumen, and not every client who can afford it has achieved his wealth through altruistic means. Capital “A” architecture should refer not to the avant garde — as it has — but to the financial status required to purchase it. What we as designers have been hoodwinked to believe is that the artistry of architecture is a universal humanist asset. What Hadid in Libya reveals is that it can just as simply be a tool.