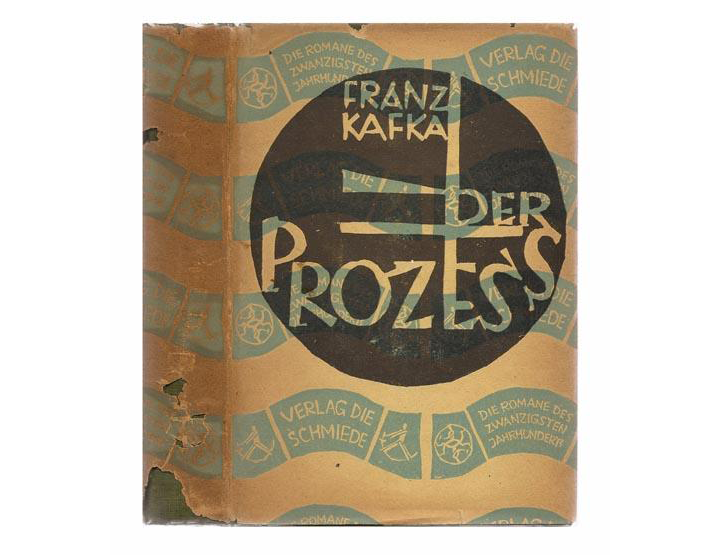

I just finished Franz Kafka’s 1925 novel, The Trial.

Why?

The first and most relevant reason: Jaron Lanier’s Ten Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now. I took up Lanier’s book out of professional obligation—I am a content strategist and social mediator—but as I turned its pages, I kept thinking Kafka! and Kafka! and Kafka! Particularly that famous first line of The Trial: “Someone must have traduced Joseph K., for without having done anything wrong he was arrested one fine morning.”

Ten Arguments suggested that, by allowing ourselves to be lured into the big connected communication machine, we risk some absurd trials of our own. Someone is always traducing someone online, says Lanier. “While not every online experience is nasty, the familiar nastiness colors and bounds the overall online experience.”

I’ve been toting around my Everyman’s Library edition of The Trial, a decidedly non-digital object, for a very long time (I’ve started it a few times and should have finished it long ago). After closing Ten Arguments, I knew it was time to re-open The Trial. I needed to measure the distance between Lanier and Kafka.

The Trial is seen as prophetic by many. Lanier made me think that there’s a new, non-clichéd dimension of The Trial’s prophecy. “Your whims and your quirks are under the microscope of powers greater than you for the first time [in the world of social media], unless you used to live in a police state like East Germany or North Korea,” he writes, adding: “How can you be authentic when everything you read, say, or do is being fed into a judgement machine?” There’s an overwhelming sense, in Ten Arguments, that what Lanier calls the BUMMER economy (BUMMER stands for Behaviors of Users Modified, and Made into an Empire for Rent) is making us as feel as surveilled and vulnerable as K. If you go to page 88 of my copy of Ten Arguments, you’ll see some scribbles saying: “Kafka would have understood BUMMER perfectly.”

In The Trial, representatives from the Court invade K’s apartment, set up shop in a sort of torture room in his offices, and even show up in a cathedral (as in the scene below). Listen closely, and you can hear that K. is both familiar with having to (a) prove his identity all the time, and (b) having people already know who he is before identifying himself—a familiar dichotomy to any user who has ever experienced the online world.

“You are Joseph K.,” said the priest, lifting one hand from the balustrade in a vague gesture. “Yes,” said K., thinking how frankly he used to give his name and what a burden it had recently become to him; nowadays people he had never seen before seemed to know his name. How pleasant it was to be recognized! “You are an accused man,” said the priest in a very low voice. “Yes,” said K., “so I have been informed.” “Then you are the man I seek,” said the priest. “I am the prison chaplain.” “Indeed,” said K. “I had you summoned here,” said the priest, “to have a talk with you.” “I didn’t know that,” said K.In our social media world, the possibility of getting unfairly accused grows greater and greater all the time. If an online mob decides to go after you, it can be perilous to your career and life, and you might be, like Joseph K., hard-pressed to stage a civilized, effective, evidence-based defense. The mainstreaming and scaling of propaganda is here today; the era of deep fakes is scheduled to arrive tomorrow.

In truth, my own personal experience with social media has been very positive: I’ve made some great friends online and have learned a lot, but that’s only the part of the experience that’s visible to me. It’s what’s done with the digital exhaust I’ve created, and what might be done, that worries me.

Fact is, designers, even if your online life isn’t generally contentious, it’s undeniable that social media can be turned in horrible uses. We’d be wrong to expect that everyone’s social experience is benign.

The dangers posed to both free-thinking and -speaking individuals are real. What you say can be distorted, decontextualized, and wielded, with violence, against you. “Speaking through social media isn’t really speaking at all. Context is applied to what you say after you say it, for someone else’s purposes and profit,” writes Lanier.

We have created our own publicly curated intelligence files, on ourselves—we just never assumed that there would be people or institutions that might use them against us. Catastrophe has been a blind spot, and this will become more precarious as IoT makes the internet disappear.

Of course, the idea of the vulnerable individualist is not new. Vladimir Nabokov warned us, in his posthumous Lectures on Literature (1980): “The color of one’s creed, neckties, eyes, thoughts, manners, speech, is sure to meet somewhere in time of space with a fatal objection from a mob that hates that particular tone. And the more brilliant, the more unusual the man, the nearer he is to the stake. Stranger always rhymes with danger.” I thought of this reading both Kafka, whose Metamorphosis gests the Nabokovian treatment in Lectures, and Lanier. What Nabokov couldn’t have possibly known was that, in the 21st century, technologically enhanced mobs could operate with a speed and agility previously undreamed of by pre-digital trolls.

The Trial is important because it gives us the chance to feel, deeply, at length, what being traduced is like. And it serves as a warning to those who are designing tomorrow’s social groups and tools and policies.

Here’s a surprise: I found reading these books a positive experience. If I could magically require our leaders to read The Trial and Ten Arguments in tandem, I would. (And, yeah, I know the legitimate perils of assigning required reading; I used to teach undergrads…) Here’s why: reading them together makes a reader both think about and feel the paranoia of today’s connected, concerned citizens. Too few people, particularly our leaders, are willing and able to say, “Privacy is dead” or “Incessant surveillance is inevitable—just get used to it.” The books "shake us awake" as Kafka says, and prompt us to think that maybe we need to find another way. This piece offers a vision for creating a future that is more autonomous than automatic. We should, for instance, be more transparent, seriously incorporate user needs, and build in more personal control.

As for now: To operate our current digital environment, without thinking about the reflexive defensiveness it creates, without being transparent about user data and such, is an unwise move. Naïve optimism about our online world is a dangerous thing. Which is why those who care about design and innovation—those of us who will create and those of us who will use tomorrow’s digital world—should first give The Trial and Ten Arguments a read. They remind us of our responsibility to craft a digital world in which we’d want to live. The future needn’t be a Trial.