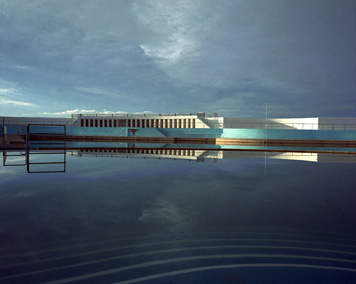

Broadstairs Sea Pool, Isle of Thanet, Kent, 2002

Tidal pools, also known as seawater pools or lidos, were once common along the coast of Britain, particularly at seaside holiday resorts. Their function was to enclose and retain a sufficient depth of seawater in which children and adults could swim after the tide had retreated from the seashore. Some were more elaborate than others. There were simple concrete pools no more than 50 by 65 feet, with a depth of less than 3 feet, for children to play in, as well as enormous concrete barrage constructions across whole bays, with sun-bathing terraces, cafes and promenades, diving boards and changing rooms. On a hot summer’s day, these larger pools became walled maritime cities in their own right, teeming with people.

Jubilee Pool, Penzance, Cornwall, 2002

Most of the pools were constructed in the 1920s and 1930s, when the culture of sunshine, fresh air and physical well-being (or to use the then-common German word lebensreform) was at its peak across Europe. It was believed that the tired, white bodies of the urban working classes, plagued by TB and other diseases, could be restored to health through exposure to the reviving properties of sun and salt water. This was also a time when British workers began to get paid holiday leave, and to spend it at the seaside: soon, coastal towns were competing to provide bathing and public recreational facilities.

Perhaps the most famous tidal pool of all is the Jubilee Pool at Penzance, in Cornwall, on what was once known as the English Riviera. Designed by the Penzance municipal engineer Captain F. Latham, the pool was opened in May 1935 to celebrate the Silver Jubilee of King George V. Its sinuous curves reached out into the sea, and its huge walls, terraces and balustrades, painted white and blue, were intended to evoke the Mediterranean world of the Côte d’Azur, or even an ocean-going liner. Because of its spectacular design, with a strong flavor of Art Deco, that pool now enjoys “English Heritage” status and was reopened in 1994 after major renovation.

Other tidal pools have fared less well. Many have been demolished, such as the one at South Bay, Scarborough, which disappeared shortly after this photograph was taken. The rest simply lie in ruins: archaeological relics from a more innocent time, before swimming pools became associated with Hollywood and hedonism, and the British abandoned their own seaside resorts for those of France, Italy and Spain. And yet people are reluctant to completely abandon them, and they retain a cult following amongst lido enthusiasts.

There is something mysterious and even disturbing about these pools, located on the border between land and water. There is a muscularity and even brutalism to most structures that engage directly or indirectly with the sea — not just tidal pools but also harbor walls, esplanades, piers, lighthouses, military lookouts and gun emplacements. All such constructions tend to be great works of public engineering, although they possess a distinctive architectural mass and form. For the sea is a powerful force of nature, and while the daily tides can bring pleasure and replenishment to coastal settlements, they are also agents of destruction and chaos. In the late 2Oth century, many maritime towns in Britain turned their backs on the sea and embraced the urbanism of popular consumer culture; lately, they are looking to the sea once again in order to rediscover their historical identity. This return to the water may yet save tidal pools from extinction.

The French town planner and philosopher Paul Virilio, writing about German bunkers constructed along the coast of France during the Second World War, compared their monumental design to the funerary architecture of the Egyptians, Aztecs and Etruscans. Many of the larger British tidal pools retain elements of ancient religious spaces, points of gathering and communal baptism and worship, with columns and arcades, a proliferation of steps and lookouts and ceremonial terraces dedicated to the sun. Like Aztec pyramids and Etruscan tombs, many of the great tidal pools are ruins, and local authorities and coastal organizations are powerfully tempted to remove them completely.

Walpole Bay Sea Pool, Margate, Isle of Thanet, Kent, 2004

This process is now being challenged. For ever since Count Volney published Ruins of Empire in 1795, one of the most influential books to come out of revolutionary Europe, it has been impossible not to find in ruins traces, intimations and lessons from the past. These remind us that human cultures are sedimented and that both archaeology and architectural history put fascinating and convincing form to earlier social arrangements and structures, even though modern capitalist development seeks to wipe most evidence of the past clean. Similarly, it was at the shoreline that the fossil record was first discovered and geology yielded its great secrets to skeptical Victorians, challenging the existence of God. It is often at the border between land and sea — usually when we are children — that we first have intimations of our own insignificance, as well as a countervailing sense of an irreducible self. These great early-20th-century pools are monuments to those experiences and emotions.

The light is different where the land meets the sea. The sky is bigger, the sea stretches toward the horizon, and this sense of space and endless reflection is enhanced by the great, smooth planes of water enclosed within tidal pools when the wind has died. Unlike most other forms of architecture, the pools gain their meaning and structure when the sea reclaims them each day anew. In Jason Orton’s atmospheric photographs, the utopian imaginings of those early pioneers of health and bodily recreation are revealed again, and still possess the power to shape the future.

Walpole Bay Sea Pool, Margate, Isle of Thanet, Kent, 2004

This essay was first published in Citizen K, Spring 2009.

Jason Orton’s photographs combine topographical observation with a more personal, psychological interpretation of place. His work has been published in Art Review, Big, Blueprint, Citizen K, Domus, The Drawbridge, The Guardian, Mare, Next Level and Ojodepez.