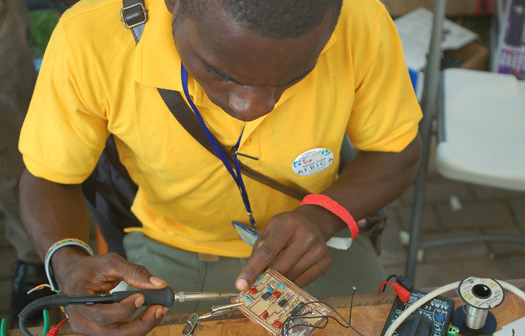

African Ladies by Madam Cora Taylor. All images from White African: Maker Faire Africa, Ghana 2009

Emeka Okafor is a New York–based entrepreneur and blogger who curated the 2007 TEDGlobal conference in Arusha, Tanzania. A reporter on innovations in African design, technology and industry, he aims to spread knowledge and foster partnerships that will lead to bottom-up growth on the African continent. One vehicle for accomplishing this is Okafor’s website Timbuktu Chronicles, which combines news of recent inventions with essays on African design and manufacturing. Another is Maker Faire Africa, an event he launched last year in Accra, Ghana. MFA brings interdisciplinary inventors and crafters together to share knowledge, resources and opportunities. This year's fair will take place in Nairobi, Kenya, August 27–28. Okafor spoke with Change Observer's Meena Kadri on July 22, 2010.

Meena Kadri

Maker Faire Africa is dubbed a celebration of African ingenuity, innovation and invention. What is the nature of the celebration?

Emeka Okafor

Many DIY-types — designers, inventors, hackers and tinkerers — in Africa work in isolation, so part of the celebration is about bringing them together to enhance, cross-pollinate and provide insights into the wider impact of their innovations on society. Taking the focus away from extractive ventures, we instead focus on those that are doing, making and producing. Globally there is a re-examination of manufacturing, production and design that is moving past the classical industrial sense and pointing to more distributed forms of production. Moving beyond mere celebration, there is also an interest in the interchange between these emerging global dynamics and local inspiration in Africa. This speaks to a far-reaching conversation in which the questions are posed: “How do we regain our creativity? How do we redefine what we mean by a society that is advanced?”

Kadri

What have you been able to build upon from last year as you head into your second Maker Faire Africa?

Okafor

The first time round was a complete experiment, and no one (including us) knew quite what to expect. Initially there was some confusion amongst the press, makers and visitors about whether it was a science fair, a conference or a trade show. They soon came to understand that we were providing a platform; if you’d made something unique and resourceful that responded to a need and showed an adaptive sensibility, then you would be valued. Many African societies are harshly delineated based on what school you went to, what degree you have and what family you’re from. At MFA we were looking to demolish these lines and instead focus on what you had produced. Whether someone went to MIT or didn’t go to school at all was of no concern. We were about creating space for discussions of what people actually brought to the table.

This notion of previously unheralded ingenuity quickly gained momentum as the event unfolded. It was heartening to see makers realize that being an inventor could provide inspiration for others. MFA started sowing the seeds for people to validate their own spirit of invention. This year we hope to extend the community of makers and innovators while building on this self-confidence.

In fostering a community, we knew that interdisciplinary exchange would be important. If you place a tinkerer who works on the side of the road next to an Ivy League engineer, dynamics are bound to get interesting. Folks begin to recognize, reassess and remix value. It’s possible to spark interaction between an electronic innovator and a textile fabricator when you encourage the notion of equivalence based on ingenuity. We also found that local awareness was raised even between those working in similar sectors who were previously isolated within the same city. Rather than looking beyond Africa for talent and resources, many started to recognize these in much closer proximity. So we’ll be seeking to build upon cross-pollination on many levels while watching for the unpredictable flourishing this yields.

A range of innovations from Maker Faire Africa 2009 spanning furniture, electronics and sanitation devices

Kadri

How do you seek out the makers?

Okafor

Via word of mouth with a large dose of cajoling into participation. Unlike DIY-ers in the U.S., many makers in sub-Saharan Africa are producing out of necessity so require convincing to participate in a celebratory venture. Many don’t have access beyond cell phones, and the self-organizing channels of Twitter, Facebook and email are not always an option. We still hope that the benefits of interaction will become clear and that makers will begin to form a self-sustaining community that evolves between events. This way established participants will be able to encourage and mentor newcomers while tracking ongoing success and the makers themselves will become significant drivers of MFA. Eventually as they gain momentum in appreciating their own collective resources and capabilities, we hope our role as organizers will be to merely increase the incline of the road ahead.

This year we’re aiming for a rich offering of inventiveness spanning robotics, digital fabrication, software, glass-making, textiles, food processing, blacksmithing and agriculture. We’re seeking out fusion areas that break down barriers between sectors and we’ll be pursuing interdisciplinary play. This is something I came to appreciate in curating TEDGlobal in Africa. When you place the biochemist next to the poet or the visual artist next to the physicist, you can rely on synergies springing from their shared curiosity. For MFA, makers are still coming to light, as they did last year, right up until the week before. It ends up being a bit like building a plane as you fly.

Kadri

What are your thoughts on the relationship between manufacture/fabrication and poverty reduction?

Okafor

If you look at industrialized countries, you'll find common, far-reaching success in surmounting poverty through developments in manufacturing. How can we industrialize without making tools? And yet development experts don’t tend to focus on manufacturing, fabrication and industrial design, which can create the resources to pursue challenges at the center of their conversations, such as health and education. And if they do pay some attention, there’s a tendency to suggest that industrial-oriented equipment be introduced from outside, which sidesteps the full benefit of sustained, local resource generation.

A crucial sector that’s been ignored is the informal industrial clusters that thrive across the African continent, churning out things that people need. It was this kind of small-scale, local enterprise that Italians and Germans built upon as they industrialized. Jua kalis [self-trained vendors offering services at informal marketplaces] provide fertile ground for bottom-up innovation, indicating a pervasive, adaptive and resourceful approach that deserves attention in development dialogue. We’re also now seeing the rise of technology-enabled products coming out of African fab labs, which address challenges like connectivity. These emergent forms of fabrication stand alongside traditional forms in providing avenues for advancement. Besides solving everyday problems with African ingenuity, manufacture and fabrication hold the key to generating reserves that can ensure ongoing development.

Kadri

Any comments on the recent humanitarian design vs. design imperialism discussion that has sent ripples through the blogosphere?

Okafor

It reminded me of the broader debate between William Easterly and Jeffrey Sachs, in which many arrows were shot in defining the best path to development. I see merits in points from Nussbaum, Pilloton and others, but I do wonder about the actual relevance of such voices of self- and media-appointed authority. Are their perspectives far-reaching in regards to what’s already happening from the bottom up? In that regard I caution myself to listen and learn, to seek out local knowledge and solutions rather than ignoring them in order to validate my own.

If one speaks from a podium, it’s not likely to really trigger a conversation. I’m hoping that these discussions will start to happen more at the sites of active knowledge exchange rather than just virtually, between designated guardians of dialogue. This is one of our aims at Maker Faire Africa: to foster interdisciplinary conversations that keep people humble because no one is an all-embracing expert. And that’s where things get interesting — and worthy of celebration.