#TBT: Michael Bierut originally wrote and published this in January 2004. Trust us, it's just as relevant today.

It was too cold to even think about going out in the sunshine, and I had spent about two hours at my computer, following links from blog to blog. Moving irresistibly from gawker.com to kottke.org to adrants.com to liberaloasis.com to moveon.org and on and on, it's easy to lose track of time. Finally, fatigue set in, as well as a bit of disgust that I was wasting an afternoon meandering through a lot of barely connected ideas.

I turned to my chores for the weekend, which included putting away a bunch of books that my wife had been piling up. One was Pale Fire, by Vladimir Nabokov. I opened it up, and immediately found myself back in that same world, but this time in the hands of a master. In 1962, Nabokov not only anticipated the linked world of hypertext, but also created that genre's first — and only? — undisputed literary masterpiece.

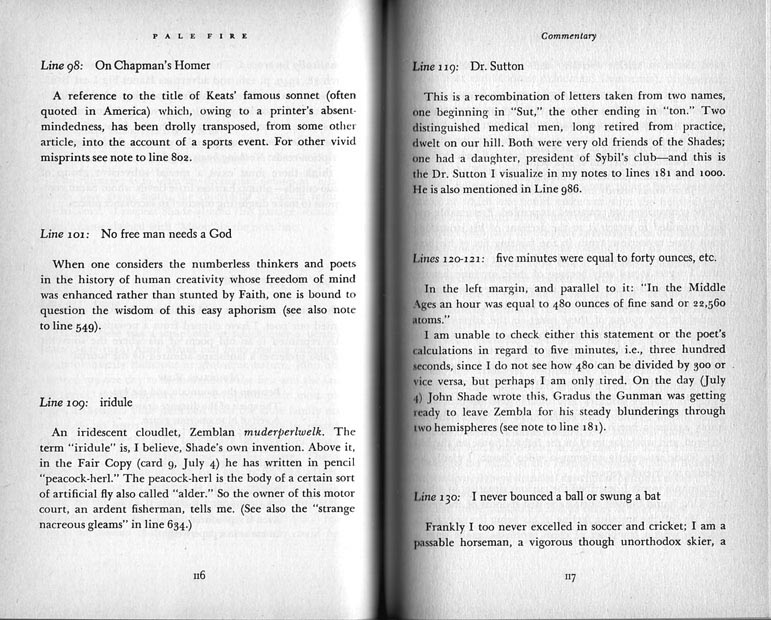

I would claim Pale Fire as one of my favorite books, except it has so many rabid fans that I'm not sure I qualify to join their number. If you aren't familiar with it, it's one of the few pieces of literature that I would argue proceeds from a design conception. The book consists of four parts: a Foreword by "Dr. Charles Kinbote;" the eponymous 999-line poem by "John Shade;" more than 200 pages of Commentary on the poem by Kinbote, and an Index, again by Kinbote. The names are in quotes above because the entire book was actually written, of course, by Nabokov, who uses the fictional authors and interlocking elements to tell many stories at once — some, all, or none of which may be "true."

An analysis by Nabokov scholar Brian Boyd, Nabokov's Pale Fire: The Magic of Artistic Discovery, exposes the protohypertextual quality of the narrative in his description of the book's opening pages. At the end of the Foreword's fifth paragraph — three pages into the book — a parenthetical aside refers the reader to Kinbote's note to line 991 of the poem. If one turns forward to the note, one finds midway through it further instruction to turn to the note to lines 47-48, which in turn contains a reference to the note on line 691. Returning back to note on lines 47-48, one encounters a second reference to the note to line 62. And on and on. The whole book works that way, and we're only three pages in. Sound familiar?

Of course, Nabokov's genius is not simply that, in contrast to the multiple voices of the blog world, he's the author behind all the different parts that make up Pale Fire's universe. It's that the elaborate structure of the book is so perfectly conceived that regardless of what path you follow, you can have an endlessly stimulating literary experience. In fact, I hesitate to raise this one again, but might I suggest that Pale Fire is design and, say, Lolita is art? (Sorry, let's not get into that.)

A check on Google reveals that my Pale-Fire-as-protohypertext revelation is far from original. Entering "pale fire" + nabokov + hypertext + links turns up over 200 hits. One of these includes the interesting fact that as early as 1969, IBM had obtained permission from Nabokov's publisher, Putnam, to use Pale Fire for a demo of an early version of a hypertext-like system by Brown University's Theodor Nelson. (IBM did not go through with the proposal.)

My copy of Pale Fire — I have a first edition in not-so-hot condition — has that old book smell. There is nothing interesting about the interior layout. The cover is the same format that Putnam seems to have used for all their Nabokovs: a condensed sans serif with a bit of color behind it. When I recommend it to students, I can tell that at first glance it disappoints: this wordy old thing has something to do with design?

Trust me, it does.