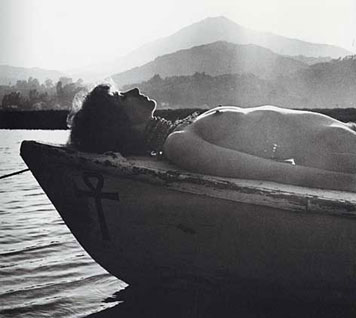

Photograph by Wallace Berman, "Shirley Berman," Larkspur 1960

The mystery of Wallace Berman's photographs revolves around the degree to which they were — or were not — set up. Was Berman attempting to create a narrative, or was he simply recording the people and events he saw around him? There's a great deal of play-acting in his photographs, and one wonders how much of it was staged, and whether or not Berman was the director of the action. Was performing for each other simply part of how he and his friends related to one another, part of the social routine, a communal project experimenting with identity, or was it all Berman's invention?

In 1961, Wallace Berman, a California-based artist, publisher of the proto-zine, Semina, gallerist, and photographer, took a picture of his landlady while he was living in Larkspur, California. We see her (the landlady!) sprawled across a bed dressed in a bra and skirt, casually holding a pistol. Clearly, this picture is not likely to be documentary (unless the rent was really late); it's better described as a photographic fiction, and one wonders what the nature of that collaboration between Berman and his landlady was. Whose idea was the gun? The question about collaboration is particularly pertinent to the numerous photographs that Berman took of his wife, Shirley, who was the subject of some of his most imaginative pictures. One wonders just how much she brought to them in addition to her extremely beautiful physical presence. One of Berman's most potent mythological works is his image of Shirley, unclothed and shot in profile, stretched across the bow of a boat with an "ankh" painted on its side. The picture evokes a reverie of oneness with the earth, as the profile of Shirley's body is echoed by three mountains in the distance that are shrouded in mist. The ankh (an old Egyptian symbol for life) appears here in its new age context, very much of a piece with the rest of the picture, underlining the artifice. This picture is one of many collaborations between Wallace and Shirley that document constantly varying notions of what constituted erotic allure.

The mountain that echoes Shirley's body in the picture looks a lot like Mount Tam, a landmark in Marin County. Many of Berman's pictures are set in evocative urban spaces or landscapes in California that are weathered and run down to such a degree that they've assumed an air of decayed grandeur. Today, places like Venice Beach or Marin try to maintain the mystique of the rusticity they once embodied, which Berman both documented and used, but of course that patina has vanished: this only serves to intensify the sense of a lost world, of a weather-beaten, poor California that can be seen in Berman's pictures.

While these lost landscapes provide a stage set for Berman's artifice, there was nothing false about the people he photographed. In their play-acting we witness them work at, or rehearse, a vision of an alternative society. In looking at Berman's pictures it's obvious that these people had lots of ideas about how to create their own lives independent of the mainstream culture that by the 1950s had become an oppressively pervasive presence in American media. They truly were operating outside, but it wasn't an outside based on criminality — it was an outside based on valuing aesthetics, freedom and independence from expectation. This isn't to suggest that none of these people had problems. Many of them did, often with drugs, and there was a lot of acting-out opposition to mainstream society in ways that were self-destructive. You can see that in the traces of sadness and depression that run through some of the pictures. This is not part of the artifice, but a sign of a life authentically, if not easily, lived.

The New York Times Sunday Magazine recently devoted an issue to what they referred to as "the new bohemia." In paging through it I was struck by the fact that every person it featured had something to sell, and that whatever genuine meaning the word "bohemia" once had has been completely drained away by contemporary forces. Things may come clothed in the image of rebellion (and Berman's pictures certainly provide a study guide for that) but that idea of truly separating yourself, or crafting a life detached from the dominant culture has been lost. The bohemianism of Berman's community was rooted in an independence based on valuing a life of the mind and a life of beauty, and they were willing to pay the full price of admission to live that way. They didn't choose to live the way they did in order to be admired, and didn't care if they were on anybody's radar. The notion of anonymity — which is something the Berman circle cherished — is completely anathematic to artists today. Maybe it's just too frightening right now.

The question of whether there are artists today making pictures that delve into ideas similar to those in Berman's work pivots on that question of how much he staged his pictures. If they were completely staged, and Berman was the author of the staging, then artists like Gregory Crewdson and Philip-Lorca diCorcia are obviously his heirs. If the pictures are primarily documentary, then the work of Nan Goldin comes to mind. It's hard to say exactly who his grandchildren are in terms of his photography. However, the one thing you can say unequivocally is that the kind of community he collaborated with, and documented so lovingly — the way it operated and the values it represented — is long, long gone.

This essay was originally published as the afterward in Wallace Berman: Photographs by Kristine McKenna and Lorraine Wild (RoseGallery Los Angeles, 2007).