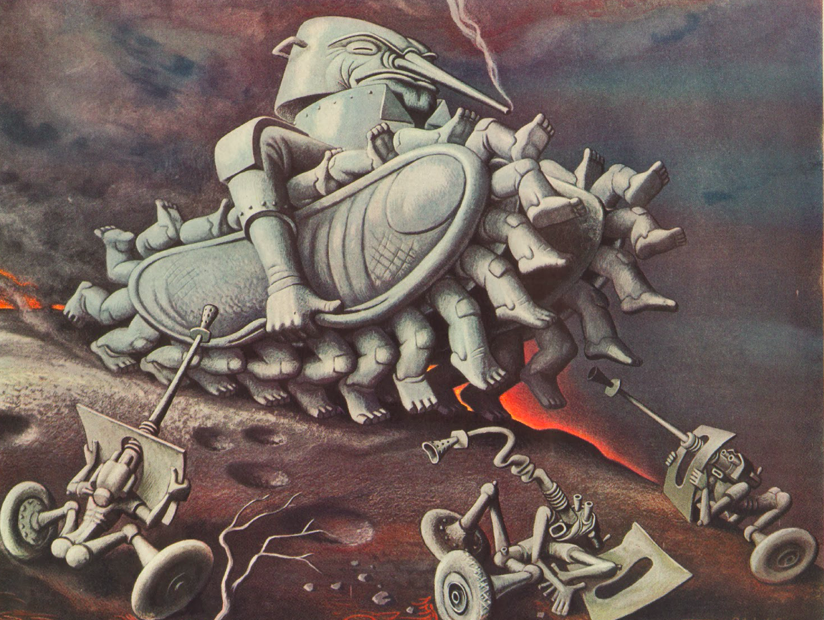

Felix Vallotton, "Verdun,"1917.

Do not be surprised by how much warfare has actually contributed to our world. From devastating destruction has arisen new machines, technologies, communications, and culture, some of it best left on the battlefield to rot and others not. In her excellent new history War: How Conflict Changed Us (Random House), Margaret MacMillan, emeritus professor of International History at the University of Oxford and professor at the University of Toronto, examines how wars have been the violent means of acquiring power, property, and protecting it too. How language and behavior have been greatly shaped by war. And how war appears to be a virus which has no cure, just lulls and Pax periods. Although this is not a design book, so many consequences of wars, including innovations through design, have emerged. The definition of war is diplomacy gone (by other means) awry; but war is also a laboratory for everything from foods and medicines to clothing, weapons to methods of controlling thought through propaganda.

Professor MacMillian’s exhaustive research into a broad span of war covers the Greek and Roman phalanx (a grid of men in battle), to the ritual of armies meeting for only one day on a battlefield for a circumscribed timeframe and then after a decisive battle determining a winner — not unlike a football or chess match — to computerized, arcade-like current wars using drones to pinpoint targets. It is disheartening to realize (especially during the rise in armed militias) that tactics and strategy, among the same concepts derived through warfare, are also used to describe branding and advertising campaigns. In fact, War is a basis for discussions about today’s design theory and practice. If you attend any branding lecture, seminar, and conference, it is likely that military principles will be imbedded in the vocabulary of the rhetoric. Even the word “freelance” comes from “free lance,” a mercenary or soldier of fortune.

Romans fighting in Thrace, 26 AD.

One chapter in particular, “War In Our Imaginations And Our Memories,” addresses the impact on art and design and vice versa. Modern war, for instance, created a need for a new visual and oral language to describe the unspeakable industrial carnage. “Plays, poems, novels, paintings, sculpture, photographs, music, and films,” writes MacMillian, “shape how we — warriors and civilians alike — imagine and think about war” that can trigger many feelings from “the heroic and glorious to the cruelty and horror.”

War is a double-edged sword for many artists and designers — for those who abhor and support — forcing them to experiment with ways of achieving emotional unvarnished and patriotic idealized depictions. Glorifying and condemning war often rely on the same visual images, only presented in different contexts. The First World War proved that the celebratory commemorations as in 18th and 19th century visuals no longer held sway. MacMillian, quoting a 1916 cultural review, says “No artist can give us a total impression of the things that go on in night and fog, under earth and above the clouds. . . The death-defying men who march past and pounce on the enemy in battlefield canvases of the old school have disappeared. In place were introduced images of terror that showed the physical cost of war.” MacMillian quotes Felix Vallotton, the Swiss painter, who was one of the most strident graphic commentators for the French satiric journal L’Assiette au Beurre: “From now on I no longer believe in blood-soaked sketches, in realistic painting, in things seen, or even experienced. Its is mediation alone which can draw out the essential synthesis of such evocation.” This is bore out in his painting Verdun, one of the bloodiest battles between French and German armies of mutilated men.

Boris Artzybasheff, "Modern War Machines," 1941.

Once war, notably in the West, was considered an honorable obligation, an oath-based responsibility to fight and die for monarch or deity and land. Twentieth century war was no longer the same kind of game with gentleman’s rules and wartime etiquette. Among the best parts of this absorbing book (again, whether or not it is read as a design text) is MacMillian’s writing on the avant garde Modern artist/designers who are the foundation of the Eurocentric canon. I quote a portion of a paragraph here:

Perhaps it was merely a coincidence that in different cities across Europe and in the New world artists were experiencing before 1914 with forms that suited the battlefields to come. The Cubists were developing a new idiom to capture the fragmentation of the world around them, while the Futurists tried to find ways to paint movement itself. In England, Vorticists wanted to smash the existing order to pieces and that, for them, meant a new geometric style that reflected the jagged nature of the world.” Which, it turned out represented the chaos of the battlefields covered with barbed wire, rocket bursts and waves of gas.To end on a definitive note that contradicts MacMillian’s superb scholarship, here Edwin Starr’s 1970 lyric says-it-all:

War, huh (whoa, whoa whoa Lord) What is it good for? Alright, absolutely nothing (war!) War