Photo: Jan Chipchase / Nokia

I recently received an invitation to discuss design and development with a wonderful group of design peers in a beautiful location. But I have decided to decline the invitation. Why?

Who needs whose help here?

I say we can do more good at home than abroad — not that we can do no good. Our skills and connections can, of course, be valuable to people in other places than our own. But if we are to exchange value — rather than just take it, like cultural tourists — what do we have to offer?

In theory, a designer's fresh eyes can reveal hidden value and thus mobilize otherwise neglected or hidden local resources. But, in practice, this hardly ever happens. The vast majority of designers go somewhere different, are inspired and stimulated and maybe even humbled by the experience — but leave without turning their insights into value that local people can use. The exchange ends up being one-way in favor of the visitor.

Hmmm.

Poverty is a real enough challenge for half of the world's population, but in many cases it's caused by patterns of development exported from and imposed by, the North.

The most powerful lesson for me, after 20 years working as a visitor on projects in India and South Asia, is that we have more to learn from smart poor people on things like ecology, connectivity, devices and infrastructures, than they have to learn from us.

Big D development tends to view human, cultural and territorial assets — the people and ways of life that are already there — as impediments to progress and modernization. A huge development industry measures progress in terms of economic growth and increased consumption. This industry often assumes without question that urbanization and transport intensity are signs of progress. It tends to devalue human agency and often imposes solutions that replace people with technology, automation and “self service.” These ways of looking at the South from the North are the result of a wrongly-developed model from the perspective of sustainability.

And it has to be said: this wrong model is making many designers rich. Around the world, from Dubai to Pakistan, the worst excesses of development are fuelled by design “visions.” One Dubai property developer has teamed up with Giorgio Armani to build thirty hotels and resorts around the world. One of these design destinations will feature in a US$43 billion luxury development on two islands — Bhudal and Bhuddo — off Karachi. Government officials describe the islands as being "deserted": but according to the Asian Human Rights Commission, the livelihoods of about 500,000 fishermen (indigenous people who have been living on the islands for centuries) will be severely affected.

Every week, it seems, another brand-name designer opens an office in Dubai on the back of a huge development. These big projects are often promoted on the basis that they will reduce poverty — but poverty is more often a pretext for developments that are primarily designed to improve incomes and lifestyles for the rich. The result, in the words of Maggie Smith, a wise and experienced development professional, is that "millions of people are expelled to the margins of fruitful existence in the name of someone else's progress."

When development ushers in a world of luxury resorts and service industry jobs, most local people end up less secure than they were before. When the possibility of living off the land and sea is removed, only a tiny minority of displaced attain formal employment. Most (and we are talking by now about a third of the world's population — two billion people) live outside the economy of secure jobs, mortgages and pensions.

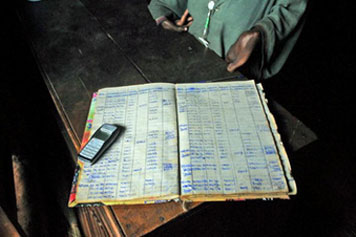

Many property developers don't even pretend to care about poor people. But in the North, a lot of people are keen to do good. Advanced Micro Devices and Architecture for Humanity, for example, ran a $250,000 competition for the design of technology centers in the developing world. AMD spoke proudly of its ambition to connect 50 percent of the world's population to the Internet by 2015. The organizers seemed to be unaware that in India, six million mobile phone accounts are being opened each month without the participation of a single "technology centre" and that smart poor people are often ahead of the game in their access to connectivity, devices and infrastructures.

Donating information technology for development is not, of itself, virtuous. Connectivity is more about the design of clever business models than about the mass distribution of devices. Delegates to the Doors of Perception conference back in 1994 were mesmerized hearing how the extraordinary Sam Pitroda enabled hundreds of millions of people in India to gain access to telephony by designing the Public Call Office (PCO) concept — a low-tech, high-smarts system based on the clever sharing of devices and infrastructure. PCOs exemplify the kind of design skills that we need to learn from India and adapt to our own situations.

An entrepreneur from the North who understands this, Paul Polak, helps people in developing countries improve water extraction and distribution systems. Polak has concluded, after years of work, that the design and technology of a device, such as a pump, is not much more than ten percent of the complete solution. The other ninety percent involves distribution, training, maintenance, service arrangements and the development of partnership and business models. These, too, must also be co-designed.

This is why I'm declining the most enticing invitation I've received in ages. I wish my friends well in their meeting, but my personal view is that it's time to get out of the tent more.