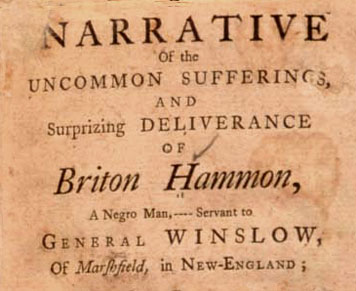

A Narrative of the Uncommon Sufferings. Boston: Green & Russell, 1760 Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress

Occasionally, I ask my sleep deprived and overworked graduate students to pitch me the Hollywood log-line variant (sometimes known as the elevator pitch) of their thesis — that truncated, pithy version that summarizes both topic and tone in one glorious sentence, about as short (ideally, shorter) as this one. It’s hard. And it’s necessary, because it cuts through the intellectual clutter of what might best be described as murky reasoning by obliging the student to commit to what’s important and, in so doing, to name it.

If brevity is next to Godliness, the trenchant beauty of the minimalist log-line stands as its most ardent advocate: but what can be said of the equally provocative — and growing need — for the full-length feature version of our stories and, by conjecture, of our lives? Once separated by the subtlest of fault lines, these two methods of delivering stories — one indexical and terse, and the other, rich in its full-blown completeness — currently reside at opposing ends of a fascinating chasm. Does daily, virtual posturing reduce our capacity for long-form empathy? Does our personal link to heritage and history lead only to traditional methods of recording our tales? Will one emerge as the dominant narrative form, or can we have both?

Of course, the summary sentence is hardly unique to Hollywood (or, for that matter, to my graduate students). It surfaces everywhere from pull-quotes to tag-lines, tagging to texting, and is, for that matter, the very raison d'être of the Twitter update. Take these one-liners out of context, and you have the formula for comedic success that characterizes the brilliance of, say, someone like Jon Stewart: it’s probably worth saying that entire broadcast networks can now be built on the premise of the single, spectacularly decontextualized detail. Yet at the same time, there’s never been a greater interest in narrative — tales spun along the classic trajectory of beginning, middle and end — that at its core, represents the opposite side of the coin.

So, what’s the story?

Clément Gallet, 2008

New Yorkers of a certain generation may recall the Hey, Jerry — What's The Story? commercials from the late 1970s that were far more successful than the electronics merchant (and later, disco owner) they represented. It is the slogan rather than the salesman — or, for that matter, his businesses — that's endured, placing it in the pantheon of memorable one-liners that bespeak the consumer habits of a forgotten generation, and reminding us that the true provenance of the pithy statement comes perhaps not so much from literature as from advertising. (Of these, my personal favorite — Where's The Beef? — is as funny today as it ever was.) Clara Peller's brilliant performance notwithstanding, it's an odd thing to privilege acronyms over actual language, slogans over substance. And yet we do.

Sometimes, though, we remember things only in context. When I was a child, listening to music meant listening to albums, the songs recorded in your mind in the order in which they were, in fact, recorded on vinyl. If you heard a certain song playing on the radio, you fully expected the subsequent song from the actual album to follow suit, because that's how you listened to your albums, for hours on end, memorizing the ending of one track into the beginning of the next one, and singing along — loudly, I might add — while your poor parents tore out what remained of their hair in an adjacent room. Now, a generation later, I am a parent myself, driving in the car with my children as they seamlessly narrate an asynchronous playlist — a mash-up of discordant selections obliging them to occasionally help me make sense of how we went from Spoon to Radiohead to Sigur Ros in under four minutes. On television, they’re mesmerized by something called Current TV, which is its own kind of mash-up — citizen journalism meets video diary, a series of unrelated documentary shorts, playing to the short-attention-span that frames contemporary culture in general and my children in particular. The interface transforms the egregious TV bug into a strip of gracefully composed miniature rectangles which tease upcoming segments: its like a GPS for your TV. (For some reason, Current TV reminds me of the signage at the Madrid Airport, where gates are listed alongside the approximate amount of time it will take you to walk to them: both essentially succeed by projecting future lapsed time — two minutes until the next video, four minutes to the next gate — thereby providing a kind of information that leads you to think, however fleetingly, that you’re actually in control of your own fate.)

Existentialist considerations aside, lack of control is precisely the premise required for a good laugh, and the sheer magnitude of 24x7 cable programming the world over offers unlimited fodder for anyone looking for material: enter the pundits, the DJs, the late night talk show hosts and no shortage of comedians. It bears saying, too, that the lure of the decontextualized tidbit is equally comical in transforming the Facebook update into a kind of force-fed Haiku. If not necessarily funny, it's at least mildly entertaining, reminding us that there's a particular pathology for those who persist in updating their whereabouts hourly — and suffice it to say, comedian is not the name for it.

Nevertheless, the pithy, out-of-context statement is becoming its own narrative form. Yet despite its appeal, it is almost singularly flawed: isn't it by its very nature meant to perpetually self-destruct? (How else to make way for the next one-liner?) On one hand, it's blessed with the patina of abstraction, a gestural cast-off intentionally divorced from context lest it appear too serious. On the other hand, it has a remarkably definitive, ex-cathedra quality worthy of oratory scrutiny: if less is more, shouldn't less be better? Or is it enough to say that brevity, when combined with frequency, and change, and Blackberry-enabled round-the-clock access, makes for a kind of unprecedented control? In this view, random pronouncements are by definition decontextualized, because the ultimate context, after all, is you.

But another kind of control comes from recapturing memory — where context, it should be said, is everything. The beauty of Storycorps operates from this notion, as does the rise of interest in geneology and family tree reconstructon and yes, scrapbooking. (Somewhat paradoxically, scrapbookers are more capable of maneuvering the discordant in their work, which arguably elevates their street cred: indeed, they embrace traditional narrative conventions while engaging in the more experimental opportunities afforded by cutting and pasting in, frankly, whatever order they see fit.)

This question of order may, in fact, be key. Is there some human need to experience stories with beginnings, middles and ends? The existence of hieroglyphs and cave paintings might support such a hypothesis, and here, I’d probably say that cartoonists — who shape stories for us visually — are perhaps the most direct descendants of these antidilluvian, if noble forms. Readers interested in understanding how drawing a story deconstructs and repositions the passage of time would do well to run out immediately and read anything by the extremely insightful Scott McCloud. The multi-panel geometric constructions by artists like Chris Ware (and the less-known but no less extraordinary Charles Forbell before him) both speed up and slow down our perceptions of individual story moments, as does the work of any of a number of graphic novelists and experimental filmmakers.

Which suggests that perspective, too, may be key: doesn't real storytelling demand conflict and resolution, point-of-view, surprise? Sometimes, the shortest of phrases can generate the nucleus of an entirely new tale. This anthology of commissioned short stories comes to mind, spurred by a phrase — the wedding cake in the middle of the road — which was given to a number of writers to each interpret as they saw fit. As for the genre of the short story: how short is short? This past Easter, a New York City church, eager to lure younger congregants, tweeted the Passion of Christ in 140-word increments. Is it sacrilegious to abbreviate the bible into Twitter-compliant soundbytes? Or just realistic?

Recently, Columbia University announced a new program in narrative medicine, defined as “an emerging clinical discipline that fortifies the practice of doctors, nurses, social workers, therapists, and other caregivers with the knowledge of how to interpret and respond to their patients' stories.” Their website stresses the importance of something they term narrative competence (“the ability to recognize, absorb, metabolize, interpret, and be moved by the stories of illness”) which — aside from conjuring images of residents in white lab coats sitting around reading Susan Sontag — is pretty interesting. (Who but a group of doctors would use the word "metabolize" to explain storytelling? Brilliant!) Ironically, positioned against the staccato interventions of so many daily tweets, the inception of such a program — literature partnering with science, humanity tethered to reality — elevates the classic model and value of storytelling to new and considerably more compelling degrees of interest by reminding us that at the end of the day, real stories are all about people.