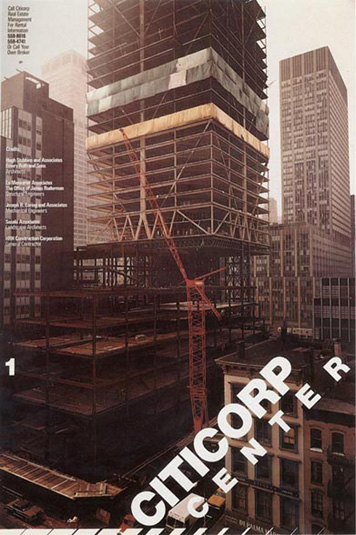

Poster for Citicorp Center, Dan Friedman for Anspach Grossman Portugal, 1975

You've taken on a design challenge and come up with a solution that's been widely admired and won you accolades. But a year or so later, you realize you made a mistake. There's something horribly wrong with your design. And it's not just something cosmetic — a badly resolved corner, some misspaced type — but a fundamental flaw that will almost certainly lead to catastrophic failure. And that failure will result not just in embarassment, or professional ruin, but death, the death of thousands of people.

You are the only person that knows that something's wrong. What would you do?

This sounds like a hypothetical question. But it's not. It's the question that structural engineer William LeMessurier faced on a lonely July weekend almost 30 years ago.

LeMessurier was the structural engineer for Citicorp Center, arguably the most important skyscraper built in Manhattan in the years of the 1970s recession. Most people who know this landmark know it for two things: its distinctive, diagonal crown, and the four towering columns centered on each of its sides that seem to levitate it above Lexington Avenue. Architect Hugh Stubbins deliberately moved the columns from the corners in order to accomodate St. Peter's Church, which had long stood on the site's northwestern edge. William Le Messurier and his engineers had to figure out how to make sure the building would stand up on this unusual base. Their solution, a series of diagonal braces and a rooftop damper to limit the structure's sway, was acclaimed for its elegance and innovation.

A year after the building's opening, LeMessurier recieved a call from a student working on a paper, asking about the unusual position of the columns. LeMessurier answered the question, but something about the conversation started him thinking. He revisited his calculations and began to realize that under certain wind conditions, the bracing might not be sufficient to stabilize the building. A series of seemingly trivial mistakes and oversights, none significant alone, had combined to create a potentially dangerous situation. His concern mounting, he consulted a fellow engineer named Alan Davenport, an authority on the effect that winds have on tall buildings. Davenport reexamined the data and confirmed his worst fears: as it was currently designed, sufficiently high winds could indeed knock down the Citicorp building. Those wind conditions, LeMessurier was told, occur once every 16 years.

The story of William LeMessurier and Citicorp Center was first told in a brilliant New Yorker article by Joe Morgenstern in 1995, "The Fifty-Nine-Story Crisis." In it, Morgenstern describes what LeMessurier faced as he realized that his greatest achievement was instead a disaster waiting to happen: "possible protracted litigation, probable bankruptcy, and professional disgrace." It was the last weekend in July. The height of hurricane season was approaching. He sat down in his summer house to try to figure out what to do. Morgenstern describes what happened next:

LeMessurier considered his options. Silence was one of them; only Davenport knew the full implications of what he had found, and he would not disclose them on his own. Suicide was another: if LeMessurier drove along the Maine Turnpike at a hundred miles an hour and steered into a bridge abutment, that would be that. But keeping silent required betting other people's lives against the odds, while suicide struck him as a coward's way out and — although he was passionate about nineteenth-century classical music — unconvincingly melodramatic. What seized him an instant later was entirely convincing, because it was so unexpected: an almost giddy sense of power. "I had information that nobody else in the world had," LeMessurier recalls. "I had power in my hands to effect extraordinary events that only I could initiate. I mean, sixteen years to failure — that was very simple, very clear-cut. I almost said, thank you, dear Lord, for making this problem so sharply defined that there's no choice to make."

LeMessurier returned to Boston and told the building's architect, his friend Hugh Stubbins, what he had discovered, that Stubbins's masterpiece was fatally flawed. As LeMessurier told Morgenstern, "he winced," but understood immediately what needed to be done. The two men went to New York and told John Reed and Walter Wriston, respectively Citicorp's executive vice-president and chairman, everything. "I have a real problem for you, sir," LeMessurier began.

Remarkably, and perhaps disarmed by the engineer's forthrightness, the bankers didn't waste time assigning blame or brooding about how to spin the situation, but simply listened to LeMessurier's ideas about how the building could be fixed, and committed themselves to do whatever it took to set things right. With Leslie Robertson, the engineer of the World Trade Center, the team devised a plan to methodically reinforce all the bracing joints a floor at a time. The repairs would take the better part of three months, with work happening around the clock. Evacuation plans were put in place; three decades ago it was unimaginable that a building would fall down in Manhattan, and no one knew how extensive the damage might be. In the midst of it all, on Labor Day weekend, a hurricane began bearing down on the northeast. It veered out to sea before the building could be tested. All of these events were largely unknown until Morgenstern's New Yorker story, because of a bit of luck for LeMessurier and Citicorp: New York's newspapers went on strike the week the repairs began.

By mid-September, the building was fully secure and the crisis had passed. In the aftermath, Citicorp agreed to hold the architect, Hugh Stubbins, harmless. And, amazingly, although there were accounts that the repairs cost more than eight million dollars (the full amount has never been disclosed), the bank opted to settle with LeMessurier for two million, the limit of his professional liability insurance. The engineer was not ruined. In fact, as Morgenstern observes, LeMessurier "emerged with his reputation not merely unscathed but enhanced." His exemplary courage and candor set the tone. As Arthur Nusbaum, the building's project manager, put it, "It started with a guy who stood up and said, 'I got a problem, I made the problem, let's fix the problem." It almost seemed that as a result everyone involved behaved admirably.

We designers call ourselves problem solvers, but we tend to be picky about what problems we choose to solve. The hardest ones are the ones of our own making. They're seldom a matter of life or death, and for maybe for that reason they're easier to evade, ignore, or leave to someone else. I face them all the time, and it's a testimony to one engineer's heroism that when I do, I often ask myself one question. It's one I recommend to everyone: what would William LeMessurier do?