In October 2023, Design Observer will celebrate its twentieth birthday. Throughout the year, we’ll be highlighting stories we’ve published over the last two decades, revisiting transformative ideas as we examine what’s continued to resonate, what’s missing, and what matters.

We begin this month with science and art.

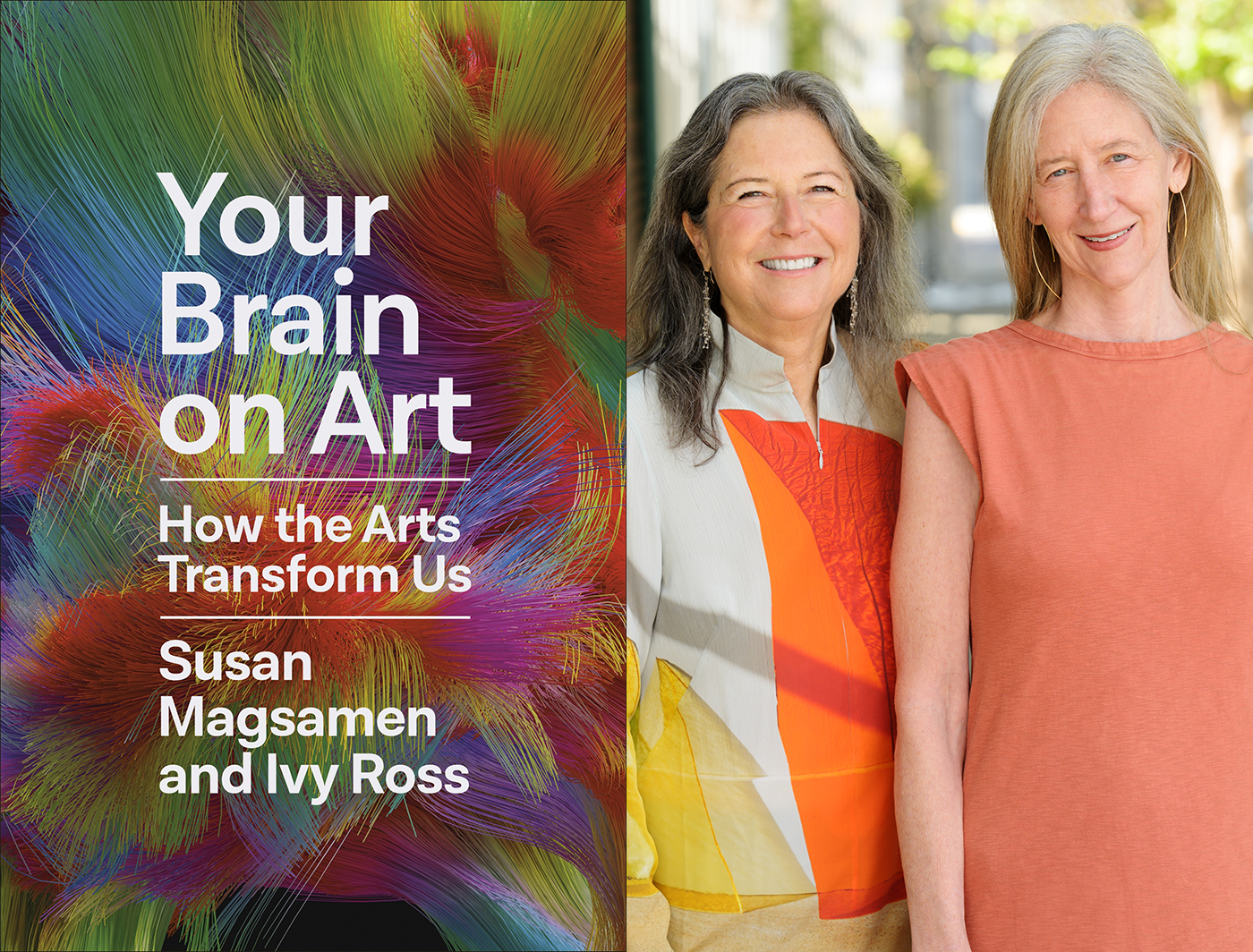

Editor's Note: From the book YOUR BRAIN ON ART by Susan Magsamen and Ivy Ross. Copyright © 2023 by Susan Magsamen and Ivy Ross. Reprinted by arrangement with Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Art as Evolution

Once humanity began to settle in regions around the world, as our ancestors created permanent encampments, Indigenous cultures began to emerge with the knowledge gained from our prehistoric family.

Art was a form of communication, and we began to perfect it as a way of expressing feelings, beliefs, and observations. “The need to make and create is fundamental to being human,” Ed told us during one of our talks. “The next stage of development expanded our need to paint, to chisel, make tools, and solve complex problems through creativity, innovation, and trial and error.”

Using the local resources of their environments, these emerging distinctive communities developed recipes and cooked. They drew and sculpted. They created clothing, body art, personal adornments, and tattoos. They refined the making of pottery, jewelry, and fiber arts, and began, even, to play with complex structures from different points of view and vantages. Aboriginal artists, for instance, created landscape maps with an aerial view.

The advent of language and writing—at first with symbols on the caves—greatly expanded the ability humans had to create. This enabled us to pass along generational knowledge and we took a great leap over other animals who had to learn survival from the other animals around them. This also gave humans the time necessary to be creative, contributing to the increase in our brain size because the more behaviors we adapted, the more brain cells were needed.

Indigenous cultures iterated creative practices and new modes of making things to convey societal values and beliefs, and interestingly, while their creations varied based on where they were made in the world, they all contained similar underlying intentions to connect, communicate, and bond. Today, there are more than 5,000 distinctive Indigenous groups in 90 countries, with around 475 million people, or about 5 percent of the global population. Each and every community is unique, and yet there are similarities in how they historically, and contemporaneously, use art and aesthetics to forge community.

To get a sense of how the arts were used to build culture in some of the earliest communities, we’re going to introduce you to cultural leaders from two Indigenous groups that exist across the globe from each other.

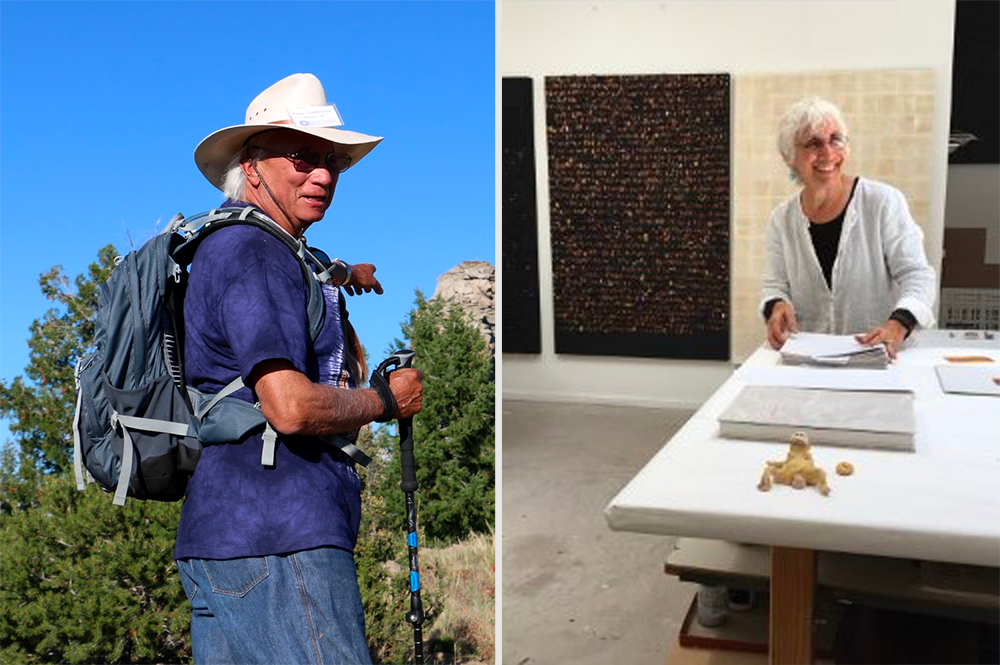

Phillip and Judy Tuwaletstiwa

We begin in the American Southwest, in the home of husband and wife Phillip and Judy Tuwaletstiwa.

Phillip is a member of the Hopi tribe. Judy is the visual artist you met in Chapter 3. We met up with the Tuwaletstiwas at their home in Galisteo, New Mexico, which sits in a valley basin with a ridgeline of red earth encircling it. On this day, we could smell the sage-tinged air as we watched the sun play tricks of light across the broad sky.

Judy welcomes us with her signature warm and inviting smile. Phillip has shown up in a T-shirt that says don’t worry bE hopi, and blue jeans, which we later learn is his standard outfit. Now in their early eighties and married for more than thirty years, they can start and finish each other’s sentences with ease.

In their home, we are drawn to their stunning Hopi kachina doll collection that hangs on the white clay walls. Hopi men carve these dolls from cottonwood roots. Kachina dolls represent Hopi supernaturals, or spirits, called Kachinas. Kachinas are part of Hopi ceremonies that date back hundreds of years, ceremonies that have grown from the Southwestern American landscape. The room suddenly feels like there are more than four of us present.

Hopi Kachina Dolls, from The Peabody Museum of Archeology & Ethnology

“Art, life, and identity were, and still are, inseparable in Hopi culture,” Judy begins. The Hopi continue to create, celebrate, and perform ritual in much the same way that their ancestors did centuries ago.

“These creative expressions reinforce the ideals of the society, and if you’re behaving properly, you’re walking the Hopi path,” Phillip adds. Ivy has known Phillip and Judy for more than twenty years. She met them at the Galisteo community center’s annual chili cook-off. Ivy had purchased a home in Galisteo in 2004 and wanted to meet her neighbors. Drawn to this town of fewer than three hundred people, Ivy often jokes that she goes there to mainline nature.

The three of them immediately connected over Phillip’s chili. “For Hopi, cooking is, in itself, an art,” he told us during our visit. No wonder, then, Phillip won the chili cook-off that day. His chili was a mixture of broth, tomatoes, onions, chiles, and a few spices. “No beans,” he says emphatically.

“At Hopi, however, a multitude of dishes are based on corn. Let me tell you about corn. Corn is life,” Phillip continues. Many ceremonies focus on corn, an essential diet staple for this desert culture. The Hopi learned to cultivate food in arid conditions, passing down the ritual of seed saving and planting through generations. “You make a deep hole in Mother Earth with a planting stick. You place a few teeny kernels of corn in the hole and cover them with the sand. The seeds sprout and grow. As they come up, they become the corn children. You must nurture them. Corn is a metaphor for life: You shelter the little corn plants. Sometimes, you build small windbreaks around them. You water them. You protect them from predators such as crows and rabbits.”

The Hopi have more than twenty different names for the life stages of a corn plant, from womb to death. Hopi is amazing in how it uses this one ingredient, in so many different dishes, transforming it. Many rituals and ceremonies were built around corn and moisture: song, dance, prayer, and story that embody the Hopi spirit and celebrate the natural world. Everyone, from children to elders, has a role to play, and everyone participates. For the Hopi, “art is a very democratic process,” Phillip says.

Hopi creative expressions take many forms, including weaving, pottery, jewelry, and carvings. Regardless of the finished piece, universal symbols represent their culture through a kind of visual shorthand imbued with specific meaning.

One, among many, beautiful examples are the kachina dolls. “The art is abstract, it’s concrete, it’s metaphoric, and it’s full of icons and symbolism,” Judy says as she holds up two very distinctive kachina dolls. The first, called the racer, is black with two red stripes across its small circle-shaped eyes and mouth. The slightly rounded corners of its rectangular head are mounted on a minimal black body with hands at the navel. The second is called Crow Mother, the mother of the Kachinas. She wears an intricate dress with high moccasins and a blanket shawl and has wings attached to her head. Judy and Phillip explain the role and nature of each of these dolls, and the ceremonies that communicate these stories.

Studies on the neurobiology of pleasure and happiness have identified the biological correlation between human gatherings such as these and the joy that shared movement and sounds produce in our bodies and brains.

During these ceremonies, the rhythm, songs, and movement of individuals meld into a whole of the group. A narrative of mystery, danger, fear, joy, pride, and pleasure are told over and over again. And through these ancient experiences a shared understanding emerges on the path of human existence.

Judy reminds us that native cultures are not tourist attractions with costumes and props. “Hopi is an ancient community in a modern world,” she says. It is through the daily rituals and profound ceremonial cycle that the Hopi traditions continue to be shared from one generation to the next, and the lessons of living reinforced.

Studies on the neurobiology of pleasure and happiness have identified the biological correlation between human gatherings such as these and the joy that shared movement and sounds produce in our bodies and brains. Dopamine, oxytocin, serotonin, and endorphins are released anytime there is a pleasurable moment, as well as when we anticipate and remember these moments. Music and dance increase levels of all of these neurotransmitters.

Through their corn and Kachina rituals and ceremonies, the Hopi instinctively activated these strong bonding chemicals to create a unified people. These community activities involving music, dance, and performance activate care and connection in our brain, where studies have shown how a deep state of altruism, joy, awe, and delight comes along with the release of dopamine, serotonin, and oxytocin.

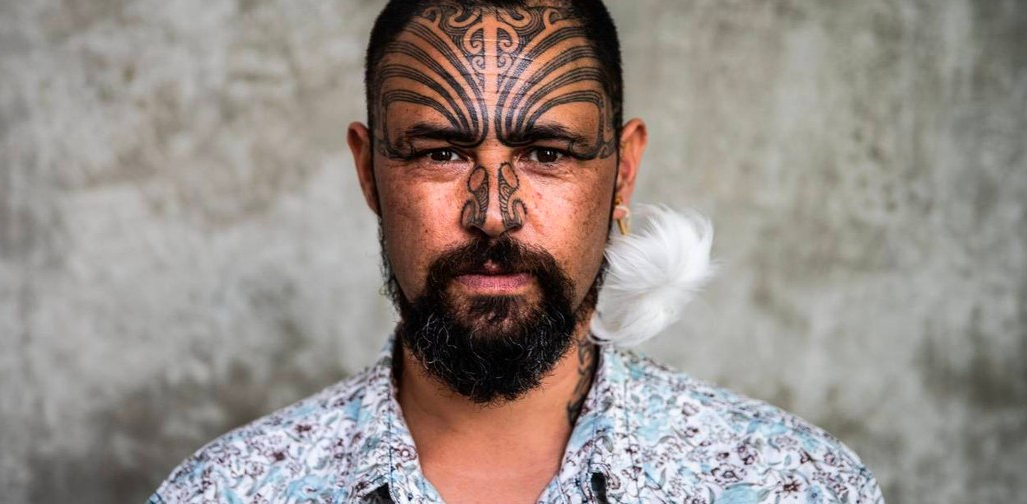

On the other side of the globe from Judy and Phillip is Jerome Kavanagh. Jerome is a composer and artist from Aotearoa (New Zealand) and a practitioner of Māori Taonga Puoro, or Māori musical instruments. Jerome comes from the North Island, where his tribal ancestors inhabited both coastal and inland areas.

Jerome Kavanagh

Jerome wears ancestral markings known as Tā moko all over his body. Tā moko reflects an individual’s whakapapa (ancestry) and personal history. Each mark is a distinctive symbol of Jerome’s family lineage, his role, and his relationship to his people. His body is a living artform honoring his place in Te Ao Māori—the Māori world acknowledges the interconnectedness and interrelationship of all living and nonliving things.

“These symbols are everywhere in Te Ao Māori,” Jerome tells us. “We have a concept called wānanga that is about creating time and space to come together. When in wānanga, these stories and rituals are shared, practiced, carried on, and built into the fabric of our culture.”

He explains that the Māori word for stories is pūrākau, which means talking tree, “so straightaway this tells you so much about our connection to nature, which is the ultimate reality,” he says. “Everything in the Māori culture and arts is about the natural world and balance. There’s a recognition that everything’s connected and everything’s important—right down to that little blade of grass, a grain of sand, a drop of water. It’s all important. One of my elders would always say, ‘Don’t talk about your river. Go and talk with your river.’ ”

Māori art serves a valuable function in daily life.

Taonga Puoro instruments were, and still are, used for healing, sending messages, marking the stages of life, and for other ceremonies. They are made out of natural materials that reflect the sounds of nature including the wind, sea, and birds.

The Māori term for creating art is Mahi Toi and is different from the Western concept of art. It is a continuation of ancestral practices connected to the cultural response with nature.

“What we do is more about respect. Our culture, our art, it is about how we serve our people,” Jerome says.

One day when we spoke, Jerome had just finished carving a Pūtōrino, a kind of wooden flute made from native Kauri wood. He spent hours making the cultural instrument for the parents of a newborn, as a way to welcome their child into the world.

“You can play this instrument in three different ways, and in the stories of this instrument there are themes of the connection and intelligence of nature and community. These stories are passed down from our ancestors to help us navigate life in the modern time,” Jerome shares. “Our cultural practices keep us connected, and it takes the Western concept of individualism out of it. The idea is that if we each bring something to the table, it’s going to be easier for everyone.”

Our conversations often come back to science, as well as art, and Jerome told us how at times he has read about a new scientific discovery in the news, and affirmed that “Māori already had that knowledge, but it’s recorded in a different way. It’s in story form. It’s in an art form. When this happens, the community has a little bit of a joke about it. Jerome says, “Wow, we already knew that. We were taught that stuff when we were little kids. And only now, they’re making a scientific discovery?”

Even as the forms we use to communicate evolve, these primary artistic skills used to communicate values persist. Rooted in our biological imperative for community, the two of us see fundamental values woven together to build connection through creative expression, the arts, aesthetic experiences, and culture. And when we put these same values into action, in even the smallest ways, we thrive.

One is holding a respect and a reverence for the natural world, which is what Ed calls biophilia. It is our human need to connect to nature and other biodiverse species. Nature is at the core of existence in Indigenous culture, too, and ceremonies and rituals were created and timed to honor natural cycles. It inspires the creation of art.

Another important tenet is making art an everyday practice. While the word “art” didn’t exist in early cultures, acts of creative expression were totally inseparable from daily living. They were integrated into the everyday, and the urge to practice creative acts was universal. Creative activities were democratized in that everyone participated, regardless of expertise, age, or gender. There was no delineation between the maker and the beholder. Diversity and complementary strengths were celebrated. There existed the ability to bring many voices, ideas, and skills to the creation of community needs, identity, and growth.

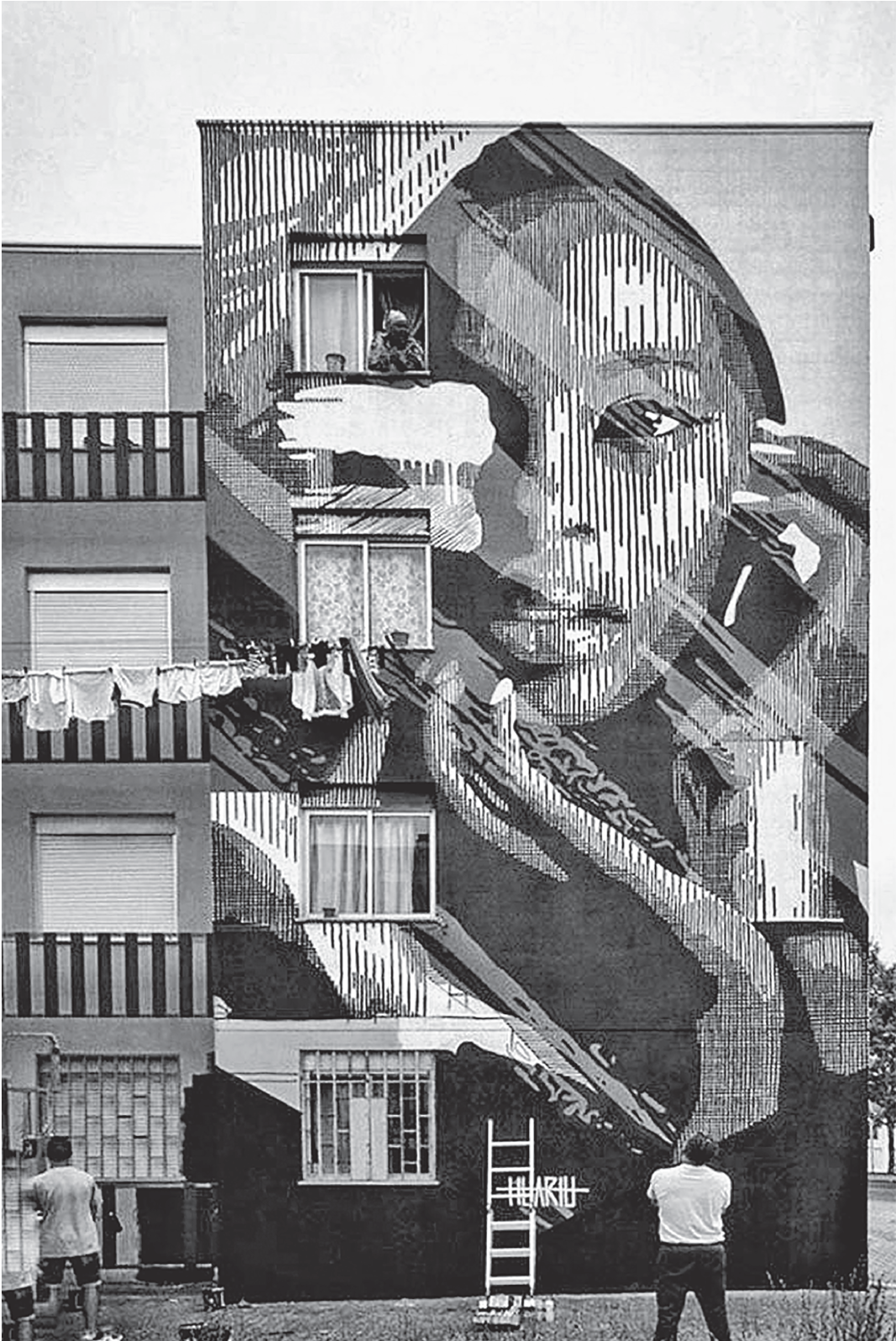

African Beauty. Fresco. Loures, Portugal. Huariu.

This use of art in the everyday helps to foster shared vision. Belief systems and community principles are expressed and reinforced using the resources available. For Indigenous cultures, this meant pottery, drawing, weaving, agriculture, home-building, and making—as well as ritualistic acts such as song, dance, and mythmaking. Today there are a vast array of materials and technologies to create meaning. A beautiful contemporary example is the creation of urban wall murals. We’ve included a piece by Portuguese street artist Huariu called African Beauty at the opening of this chapter. Huariu shared with us that it “was painted in a poor neighborhood, mostly a Black community, and the goal was to highlight and portray the beauty of the people who live there. It was a very heartwarming experience.”

Often, a larger meaning is woven in. Call it what you will—religion, spirituality, or the divine. Art lays the foundation to create transcendent moments, forging emotional bonds present in the life of community. Our culture shapes our perceptions of self. Symbolism, icons, and metaphors amplify meaning, and are often passed down from generation to generation. These cultural artifacts serve to embody the values and beliefs that keep a community strong and that help to ensure its survival. And perhaps most important, the practice and repetition of creative expression in the form of songs, stories, fables, myths, dance, and other rituals reinforce beliefs, identity, and cohesion.