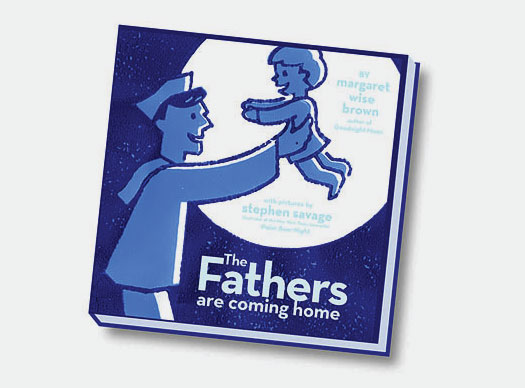

Cover of The Fathers are Coming Home, by Margaret Wise Brown, illustrated by Stephen Savage

My oldest friend never knew his father. Leigh was three when his dad was killed in Korea, his remains never to be recovered and shipped home for burial. As long as Leigh and I were friends, until he moved across the country to California at the age of 21, I noticed a gaping hole in his psyche. Since I never faced such a loss, I could only imagine his longing. My father not only came home from World War II, he came home almost every night from work. I often thought of my friend sitting in his apartment waiting for no one.

On September 15, 1943, two years into U.S. involvement in World War II, Margaret Wise Brown, the prolific children’s book author whose soothing Goodnight Moon has been a perennial favorite, signed a contract with Harper & Brothers to publish The Fathers Are Coming Home. Acquired by Ursula Nordstrom, the editor who later discovered Maurice Sendak, The Fathers was an opportune book given the number of American children whose fathers had either gone off to battle or worked double and triple shifts in local war industries. Of course many fathers didn’t return. So perhaps the subject was too timely or, more likely, proposed at the wrong time. The contract was ultimately canceled and the advance against royalties of $300 was shifted to Little Brass Band, a Brown title with a less controversial theme. The Fathers manuscript was one of 73 locked away in a cedar trunk after Brown’s death in 1952 at the age of 42. It was later discovered in 1991 in her sister’s barn.

Margaret Wise Brown, known for her economical yet eloquent texts that spoke directly to children, often in a child’s voice, had uncanny verbal instincts. Although she never had children of her own, she wrote in a soft cadence designed to replicate a child’s inner thoughts. The dozens of books she published tapped into young longings and expectations. Goodnight Moon, the most famous of them all, was also the most universal — presenting its “great green room” as a domestic sanctuary that any child might crave. The Fathers Are Coming Home was to do for aching hearts what Goodnight Moon did for tired souls, as various benign animal fathers — a fish, bug, rabbit, daddy long-legs, dog, bird, and snail — return at night to their offspring, culminating in a sailor who comes home from the sea, “home to his little boy.”

And yet in 1943, America was still more than a year away from D-Day and two years away from total Nazi surrender. In the Pacific, the Japanese, who had swooped down and captured allied territories, were fighting bloody battles for unknown beaches. Survivors of these theaters were sometimes shipped home, but they often returned to fight again. Someone at Harper & Brothers decided that 1943 or 1944 or 1945 was not the best moment for The Fathers Are Coming Home. And that person was right. Too many fathers (and boys who would never become fathers) perished. Brown’s promise of solace could not be kept. Then came the Korean War, during which Brown died from an embolism following an operation for an ovarian cyst. A decade-plus later, the Vietnam War took its toll. There seemed never to be a good time (and the manuscript was virtually forgotten anyway) until now.

“We don’t know why Harper & Brothers canceled the original contract,” says Stephen Savage, who illustrated the first-ever edition of The Fathers, finally published this year. “Brown wrote several different versions of the text, but it is hard to reconstruct the exact history of the manuscript.” Her biographer Leonard Marcus told Savage that after her death in 1952, the estate did try to get as much published as possible, so it is likely that several companies passed on this particular manuscript. “Perhaps by then publishers thought the book was dated, too tied in to the emotions of World War II,” Savage speculates.

Now, ten years into the war in Afghanistan and eight into the war in Iraq, this book may not be any easier to accept, especially by those who have lost loved ones. Yet, says Savage, “We always felt that the book would resonate today because of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. How could it not?”

“It's a bedtime book,” adds Savage, who illustrated the award-winning Polar Bear Night. “My job as the artist was to create a world that was soothing and calm and safe. It was clear, too, that the book was about World War II, so we dressed the sailor in a uniform of the period and put him on an old-fashioned ocean liner.”

Rendered in linocut (a decision made with art director Ann Bobco and editor Karen Wojtyla) and muted colors, The Fathers Are Coming Home has a grittier quality than Goodnight Moon. Savage was influenced by Jean Charlot's illustrations for Brown’s A Child's Good Night Book. “His images of sleepy animals and kids are so tender and sweet without being sentimental,” he says.

Yet this book is nonetheless melancholy. Even knowing that Dad will return does not lessen the sense of abandonment. There is always doubt; not only will the father go again, but next time he may not come home. Perhaps it wasn’t just the war that prevented this bittersweet book from being published. Perhaps it was a deeper, more primal fear.

My oldest friend never knew his father. Leigh was three when his dad was killed in Korea, his remains never to be recovered and shipped home for burial. As long as Leigh and I were friends, until he moved across the country to California at the age of 21, I noticed a gaping hole in his psyche. Since I never faced such a loss, I could only imagine his longing. My father not only came home from World War II, he came home almost every night from work. I often thought of my friend sitting in his apartment waiting for no one.

On September 15, 1943, two years into U.S. involvement in World War II, Margaret Wise Brown, the prolific children’s book author whose soothing Goodnight Moon has been a perennial favorite, signed a contract with Harper & Brothers to publish The Fathers Are Coming Home. Acquired by Ursula Nordstrom, the editor who later discovered Maurice Sendak, The Fathers was an opportune book given the number of American children whose fathers had either gone off to battle or worked double and triple shifts in local war industries. Of course many fathers didn’t return. So perhaps the subject was too timely or, more likely, proposed at the wrong time. The contract was ultimately canceled and the advance against royalties of $300 was shifted to Little Brass Band, a Brown title with a less controversial theme. The Fathers manuscript was one of 73 locked away in a cedar trunk after Brown’s death in 1952 at the age of 42. It was later discovered in 1991 in her sister’s barn.

Margaret Wise Brown, known for her economical yet eloquent texts that spoke directly to children, often in a child’s voice, had uncanny verbal instincts. Although she never had children of her own, she wrote in a soft cadence designed to replicate a child’s inner thoughts. The dozens of books she published tapped into young longings and expectations. Goodnight Moon, the most famous of them all, was also the most universal — presenting its “great green room” as a domestic sanctuary that any child might crave. The Fathers Are Coming Home was to do for aching hearts what Goodnight Moon did for tired souls, as various benign animal fathers — a fish, bug, rabbit, daddy long-legs, dog, bird, and snail — return at night to their offspring, culminating in a sailor who comes home from the sea, “home to his little boy.”

And yet in 1943, America was still more than a year away from D-Day and two years away from total Nazi surrender. In the Pacific, the Japanese, who had swooped down and captured allied territories, were fighting bloody battles for unknown beaches. Survivors of these theaters were sometimes shipped home, but they often returned to fight again. Someone at Harper & Brothers decided that 1943 or 1944 or 1945 was not the best moment for The Fathers Are Coming Home. And that person was right. Too many fathers (and boys who would never become fathers) perished. Brown’s promise of solace could not be kept. Then came the Korean War, during which Brown died from an embolism following an operation for an ovarian cyst. A decade-plus later, the Vietnam War took its toll. There seemed never to be a good time (and the manuscript was virtually forgotten anyway) until now.

“We don’t know why Harper & Brothers canceled the original contract,” says Stephen Savage, who illustrated the first-ever edition of The Fathers, finally published this year. “Brown wrote several different versions of the text, but it is hard to reconstruct the exact history of the manuscript.” Her biographer Leonard Marcus told Savage that after her death in 1952, the estate did try to get as much published as possible, so it is likely that several companies passed on this particular manuscript. “Perhaps by then publishers thought the book was dated, too tied in to the emotions of World War II,” Savage speculates.

Now, ten years into the war in Afghanistan and eight into the war in Iraq, this book may not be any easier to accept, especially by those who have lost loved ones. Yet, says Savage, “We always felt that the book would resonate today because of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. How could it not?”

“It's a bedtime book,” adds Savage, who illustrated the award-winning Polar Bear Night. “My job as the artist was to create a world that was soothing and calm and safe. It was clear, too, that the book was about World War II, so we dressed the sailor in a uniform of the period and put him on an old-fashioned ocean liner.”

Rendered in linocut (a decision made with art director Ann Bobco and editor Karen Wojtyla) and muted colors, The Fathers Are Coming Home has a grittier quality than Goodnight Moon. Savage was influenced by Jean Charlot's illustrations for Brown’s A Child's Good Night Book. “His images of sleepy animals and kids are so tender and sweet without being sentimental,” he says.

Yet this book is nonetheless melancholy. Even knowing that Dad will return does not lessen the sense of abandonment. There is always doubt; not only will the father go again, but next time he may not come home. Perhaps it wasn’t just the war that prevented this bittersweet book from being published. Perhaps it was a deeper, more primal fear.