“I can release a destructive power in a human being that would make the split atom seem like a blessing,” says the science teacher at an all girl’s boarding school to her student lab assistant in the 1957 B-film Blood of Dracula.

The teacher’s name is Miss Branding — yes, Branding — and her threat, we soon learn, is aimed at men, who for centuries have controlled women’s fragile emotions, much the way the advertising industry has manipulated their supple minds. Miss Branding employs an ancient amulet charged with magical and mystical forces to hypnotize a susceptible teenage girl to lash out against these male oppressors by sucking the life’s blood right out of them. Soon, this predatory she-beast siren, under Branding’s spell, is branded by the police as “a Dracula.”

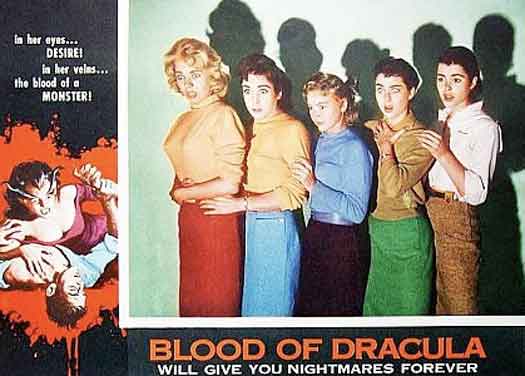

“In her eyes… DESIRE! In her veins… the blood of a MONSTER!”

Still from Blood of Dracula

Miss Branding's bewitching Amulet

So was this film a cautionary parable about the diabolical power of advertising and branding? Or was it merely a coincidence that Miss Branding’s lines sound like a twenty-first century branding consultant (albeit a bitter one)? We never really learn much more about Miss Branding or her motives, other than she is doomed by her own creation (or perhaps burned out, like so many in the ad and branding business). But we are left with the question: Do brands trigger desire? Or create monsters? (Or both?)

Before branding was Branding (with a capital B), a brand was just a common term and branding a conventional method of identifying things. Livestock was branded with a red-hot branding iron — it had to hurt the animal, but who cared as long as the mark was emblazoned for all to see. Throughout history people were likewise branded as slaves or criminals — that hurt too, but they were slaves and criminals, after all. Branding, therefore, had negative connotations, as in being branded as a liar, cheat or thief. In Nazi Germany Jews were branded by the yellow star. Elsewhere brands distinguished one people or gender from another. One was, however, never branded “a good person.”

Still from Blood of Dracula

Then there are products as brands. This practice starts in the late nineteenth century. Initially, there were trademarks, which evolved from medieval tradesmen’s marks, which derived from even earlier monarchial crests and seals. Fast forward: In the United States, increased interstate commerce gave way to national brands. In 1872 Blackjack chewing gum was one of the earliest. In 1886 Coca-Cola became one of the most prized. But local products and produce were also given the brand moniker, as in The Double A Brand, a California fruit grower, which references the Double A Ranch, which is agri-branding nomenclature.

Owing to greater communications and the revolutions in transportation, brands and branding proliferated during the early twentieth century and advertising rose to promote them. In fact, branding was under the advertising, publicity and promotion umbrella. Trade magazines, like Advertising Arts, wrote about “friendly trade characters,” like Uncle Ben, Aunt Jemima, the Armour and Cream of Wheat Man, that housewives happily welcomed into their homes.

Poster from Blood of Dracula

Brands became more than mere boxes and bags; they were human proxies — surrogates that offered a better life, as long as the consumer subscribed to the proscriptions of that life.

Enter Miss Branding. By 1957 brands ruled the consumers’ roost. American housewives (and single women too) were consumed by brands. Advertisements hawking brands were almost as powerful as the split atom. Sure, they weren’t all bloodsuckers, but they were ubiquitously influential and hypnotic. They manipulated desire, while perpetuating the monster. And this was before branding was Branding (with a capital B).