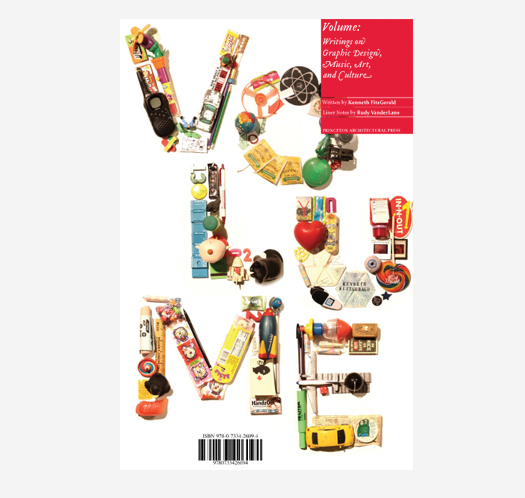

The cover of the book Volume: Writing on Graphic Design, Music, Art and Culture by Kenneth FitzGerald

It’s an odd experience to review a book in which you find yourself to be the recipient of a hearty kicking by the author. It’s even odder to find that you are full of admiration for the writer’s calm-eyed analysis of the design world. But I don’t deserve the kicking: more of this later.

Kenneth FitzGerald’s Volume: Writing on Graphic Design, Music, Art and Culture is an important addition to the library of graphic design writing. Many followers of the discourse surrounding design over the past two decades will be familiar with FitzGerald’s texts, principally for Émigré, but also Eye, Voice: AIGA Journal of Design and occasionally for this site. He is currently Associate Professor of Art at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia.

FitzGerald is a fine writer with a gift for potent phrases (“As no military plan survives contact with the enemy, no design concept survives contact with the client.”) His prose is agile, unmannered, and always at the service of strong ideas born out of wide reading and deep engagement with contemporary culture, of both high and low varieties (look out for references to Thomas Pynchon and Garth Brooks). In other words, he’s highly readable. This is important. Design critics bemoan the lack of interest in design writing (it's a near constant theme in FitzGerald’s book), but shouldn't writers bear some responsibility for this? When designers say they don't read, the onus is — at least partly — on writers to make their writing more engaging. It can’t all be down to language averse designers — can it?

Volume brings together a batch of FitzGerald’s essays and corrals them into four sections. In fact, the book reads as one longish mediation around a few recurring themes: a stubborn refusal to accept received wisdom (Lester Bangs is a hero); regret over the disinclination of professional designers to engage in critical self-investigation; the difference between art and design; design education; and the idea that the design world is as much stratified by class as any other world.

Volume opens with an essay in which FitzGerald questions his fitness to teach: “I warranted suspicion as a recent MFA graduate with ‘little or no professional practice or teaching experience’ … I was teaching some undergraduates with more professional experience than I had.” But his self-doubt is unfounded. In a later chapter he describes some of his classroom exercises. These make him sound like an inspirational instructor, and my guess is that the classroom is his natural habitat.

FitzGerald is at his incisive best when he brings his forensic gaze to bear on the class system that is built into design. In his view, the naked bones of design’s class structure can be seen in the work of elite designers employed by “celebrity-oriented, moneyed cultures (fashion, architecture, entertainment, and the arts).” His willingness to expose design’s stratification extends into his teaching strategies: “I urge students to adopt awkward methods, and embrace the unfamiliar. Often, these are no more exotic than working at a dramatically different speed. This is different from the standard academic tactic of introducing them to ‘new ideas’.” He goes on to note dismissively that “new ideas” usually means exposure to the works of established designers: “Emulating an admired artist is the standard method of directing students toward a sophisticated model of creativity … [students] are called upon to simultaneously regard and ignore the work, as we don't want them copying it.”

It’s not only his students FitzGerald wants to refrain from gazing admiringly at the great and the good of the design world. His own combative approach to criticism means that he doesn't shy away from roughing up representatives of design’s elite: Alan Fletcher (“The Art of Looking Sideways … a formless data-dump of quotations, aphorisms, diagrams, reproductions, commentaries, and folderol”); John Maeda (“sterile, programmed ornamentation”); Paul Rand (… students will become even more marginalized and disenchanted with their work and status if they attempt to define themselves by Rand’s fallacies); and Stefan Sagmeister (“Made you Look … a fatiguing compendium of almost every optical, production, and advertising-creative artifice devised since Gutenberg”).

In the final group of essays (“Inference and Resonance”), FitzGerald moves away from what we might call the politics of design to the philosophy of design. Here he mediates on the big questions that stalk the design jungle, such as graphic design’s relationship with art. He is not in the least starry eyed about art, and he’s quick to point out art world — and design world — hypocrisy and double-dealing: “It is a delusion that the activity of fine artists is divorced from commercial considerations. It isn’t even a matter of degree. All that separates art and design is the kind of marketplace one chooses to operate in.”

This willingness to attack sacred cows makes FitzGerald an entertaining commentator. But it also raises the question — what does he really believe in? Occasionally I have the suspicion that he is a sharp-brained polemicist who can muster an argument in favor — or against — any known view. This is relevant to the kicking I receive from him.

FitzGerald takes me to task for a short review I wrote of Emigre No.64: Rant for Eye (“Back on the old battleground”, Eye 48, Summer 2003). In retrospect, I admit to a bit of over-heated rhetoric, and feel chastened by the swish of FitzGerald’s corrective rod. But I stand by the gist of what I wrote. I criticized the writers in Rant for their preoccupation with a “wished for” design world where designers were free to make the sort of work that restored graphic design to its avant garde roots, yet simultaneously failed to recognise the mundanities of working life in the “trenches” — FitzGerald’s word, not mine.

The reason I stand by what I wrote is helpfully provided by FitzGerald himself: in his essay “Trenchancy”, he writes: “Consideration of the spectrum of design activity from Massimo to MacTemp usually focuses on the upscale.” My point exactly: if critics focus only on the Massimo component of design, critical writing will remain irrelevant to most designers.

And besides, not all designers need to engage with critical thinking, design theory and the higher discourse. Those of us who are perpetually examining ourselves and our craft — and doing the same to others — are often riven with doubt, fear and loathing. Sometimes it’s enough just to be good at your job. Sometimes it’s OK not to want to open the box and look inside. But after reading Kenneth FitzGerald, you’d probably want to have at least a peek.