During the twentieth century, traditional handcraft productions related to graphic design and printing were largely reduced to boutique practices. Anyone cutting metal type or running a letterpress was usually trying to keep the art alive, not operate a self-sustaining business.

On the rue St. Jacques in Paris, massive courtyards used to house print shops—owing to their proximity to the Latin Quarter universities and the need for students to publish their theses. Sibling arts flourished in the neighborhood as well, especially fine art printing—from the seventeenth through the twentieth centuries. Then, as with other analog arts, mechanization and digitization rendered them obsolete. The last standing printer's atelier on the rue Saint Jacques was the Atelier George Leblanc which—up until 2007—housed ancient stacks of felts, two-kilogram paper weights, wooden hand presses, and row upon row of prints. It was a stunning space whose days were numbered.

Most of the work drying in the atelier—which had once printed Degas, Manet, Munch, and Cassatt—was that of Didier Mutel, a young artist who had apprenticed there. He tries to actively support the traditional art presses while finding new ways to use them. In 2007, he and master printer Pierre Lallier, who had run the shop for forty years, were negotiating to save the space and have it declared a historic property. But the space was sold to a commercial developer and the atelier evicted. After a brief sojourn on the Avenue Daumesnil, Mutel moved the print shop contents to a renovated textile factory building in the town of Orchamps, just over 200 miles south of Paris, and just down the road from the University of Besançon, where he teaches printing arts and art history.

So now, the remnants of the longest-surviving printers' studio in Paris have been reconstituted along the banks of the Doubs River in the foothills of the Jura mountains.

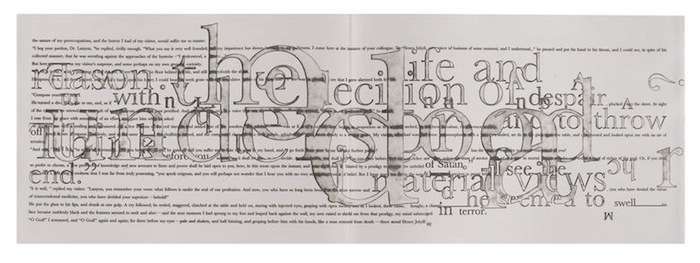

Didier Mutel trained as an artist, so he approaches printing from both aesthetic and technical angles. His book projects have combined the technology of engraving and intaglio with letterpress typography and relief printing. One of his earliest books was an edition of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. In Mutel's version of the story, as Mr. Hyde emerges to control the narrative of the novel, the letters gradually lose their grip on the paper and tumble into piles of forms at the bottom of each page. He printed the pages from photo-engraved copper plates, giving them a dimensional play this is now accomplished with polymer plates—a technology that allows great flexibility with a page's geography.

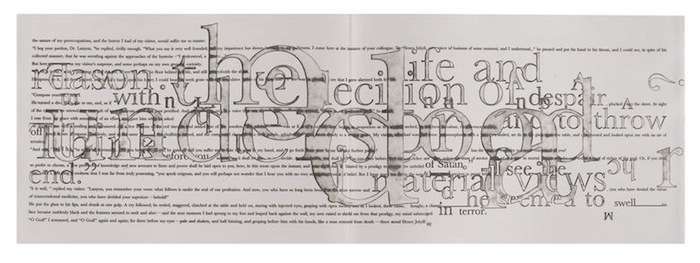

Mutel's more recent books have used classic forms to explore seemingly unrelated themes. His reimagining of the Description de l'Égypte—based on an early nineteenth-century French government project to publish maps and renderings of Egyptian antiquities—puts engraved portraits of grotesque faces in the place of maps. Each suite contains slightly altered views so that the pages can be flipped to create “movies.” His current project is a globe populated with imaginary land and water forms named for the masters of engraving: Rembrandt, Goya, Dürer. He plans a suite of the gores (the lozenge-shaped strips that are joined and pasted onto a globe) as well as a few finished globes—already on view in his showroom in Orchamps.

Mutel's more recent books have used classic forms to explore seemingly unrelated themes. His reimagining of the Description de l'Égypte—based on an early nineteenth-century French government project to publish maps and renderings of Egyptian antiquities—puts engraved portraits of grotesque faces in the place of maps. Each suite contains slightly altered views so that the pages can be flipped to create “movies.” His current project is a globe populated with imaginary land and water forms named for the masters of engraving: Rembrandt, Goya, Dürer. He plans a suite of the gores (the lozenge-shaped strips that are joined and pasted onto a globe) as well as a few finished globes—already on view in his showroom in Orchamps.

The overarching theme of Mutel's past decade of work is "acid brut." The impending destruction of Atelier Leblanc radicalized Mutel—he wrote a manifesto to alert the world to the history and importance of engraving and the printing arts, in hope of garnering support to keep the studio alive. It's been a long fight, one he is winning step by step. In November 2013, he was named a Maître d'art by the French Minister of Culture and Communication, bringing him a lot of recognition and a small bit of government funding.

Every project he has produced in the past several years has exploited the history of acid and engraving. To promote his new workshop, Mutel worked with a ceramicist to recycle thrift shop dishes to carry mottoes and themes such as "Acid Rocks" and "United States of Acid."

His most recent book, My Way II, comprises twelve prints made from copper or Plexiglas “engraved” with firecrackers or other flaming objects; his favorite involved a funeral pyre for a Playmobil nobleman. A colleague photographed the plates as they were prepared and printed and linked them together to create animated films. These short sequences, all set to music, mesmerize the viewer while challenging our notions of how art should be made. They are a modern link to Jean Dubuffet's Phénomènes, a series of etchings the artist made in the late 1950s from metal plates that he scratched, rubbed with dirt and sand and otherwise degraded. The marks revealed natural corrosion and exposure, rather than designs created purely by the human hand.

Anyone interested in the way printing helped make us modern should visit Mutel's studio. It serves as both a museum and a living workshop. In the large loft, he has installed six art presses—three of them from the eighteenth century, made entirely of wood—and a Heidelberg press for letterpress work. Much else has been salvaged from the old shop—felts, weights, tools. Perhaps the most amazing of all are the dried pigments that have survived since the mid-1800s with their vibrancy intact—golden yellows, severe reds, and blacks—and a blue that would make Yves Klein wince.

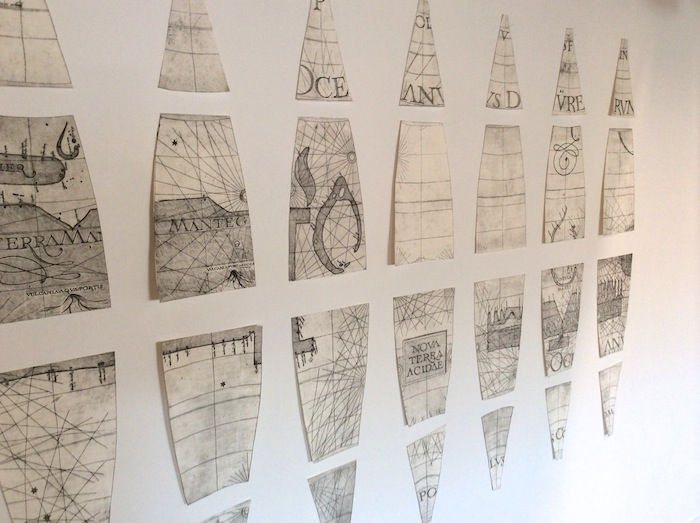

The workshop itself is a chef-d'oeuvre. Needing to build a new floor in the disused textile factory, Didier visited a neighbor—a manufacturer of oak barrels for the wine industry—and bargained for three metric tons of scrap wood. He spent months joining the small end-cuts until nearly every surface—the floor, the walls, doors and jambs—was faced with sweet-smelling wood. He carved out a small bedroom for himself and his children, installing a pot-bellied stove from the old atelier in the corner. Forget your adventure eco-vacations. This is where to spend a fortnight—carving copper plates, etching and printing them, then sharing local champagne and Comte cheese at the edge of the little river that rushes by his back door. He welcomes visitors.

Didier Mutel's website contains examples of his work as well as contact information and specifications about his publications and prints.

Photos by John Hill, except The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, courtesy Sackner Collection, Perez Art Museum