Playing cards are taken for granted. They have been ubiquitous objects in households for centuries, but they are hardly ever given the credit they deserve for what they can tell us about culture, history, and design. In my role as a curator, I work with a rich and wide-ranging collection of playing cards—everything from hand-painted medieval decks to cheap souvenir packs from the twentieth century. Forward-thinking collectors and donors made sure that these artifacts of printing were including in a library that could provide appropriate historical context.

I try to put them in historical context whenever possible through exhibitions and classroom teaching, including a recent survey about the history of printing. Several years ago, I published a blog post that showed the backs of various playing cards. It was a straightforward post that showed patterns of dots, dimples, diapers …

To my surprise (and delight), that post generated responses from a new group of readers to my blog—graphic designers. Though I was raised in a household that went through deck after deck for pinochle, cribbage, canasta, bridge … it wasn’t until years later that I started to see playing cards from many new perspectives: their design; their role in social life; what they can tell us about printing history.

A newfound fascination focuses on the secondary lives of playing cards. By looking through library catalogs and collections of ephemera, I found cards have that been repurposed for many different uses. Think about it—you’re living in the eighteenth century, of a class that can afford a set of playing cards (and of a religious bent that did not forbid them). If one card from your lovely deck ends up getting lost or smudged or burnt, or otherwise becomes unplayable, you can fudge with a handmade replacement. But if you lose two, you’re luck is starting to run out; you’re … ahem … not playing with a full deck.

What to do with the remaining cards? Keep in mind that up through the beginning of the twentieth century, paper was not inexpensive. Often, those leftover cards were kept and recycled. They were employed as note cards, business cards, and calling cards. (This, of course, applies only to cards with plain backs, which was the case with many decks through the eighteenth century.)

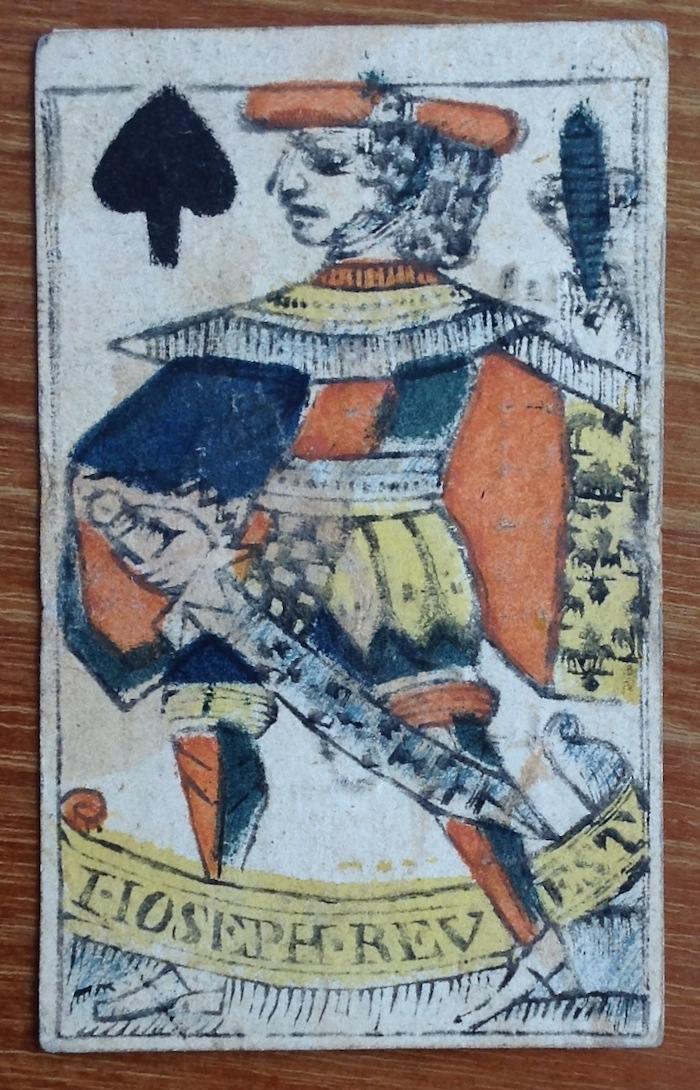

Here is a selection of playing cards that found new lives through the ingenuity of the pen, the printing press, and, in one case, a pair of scissors.

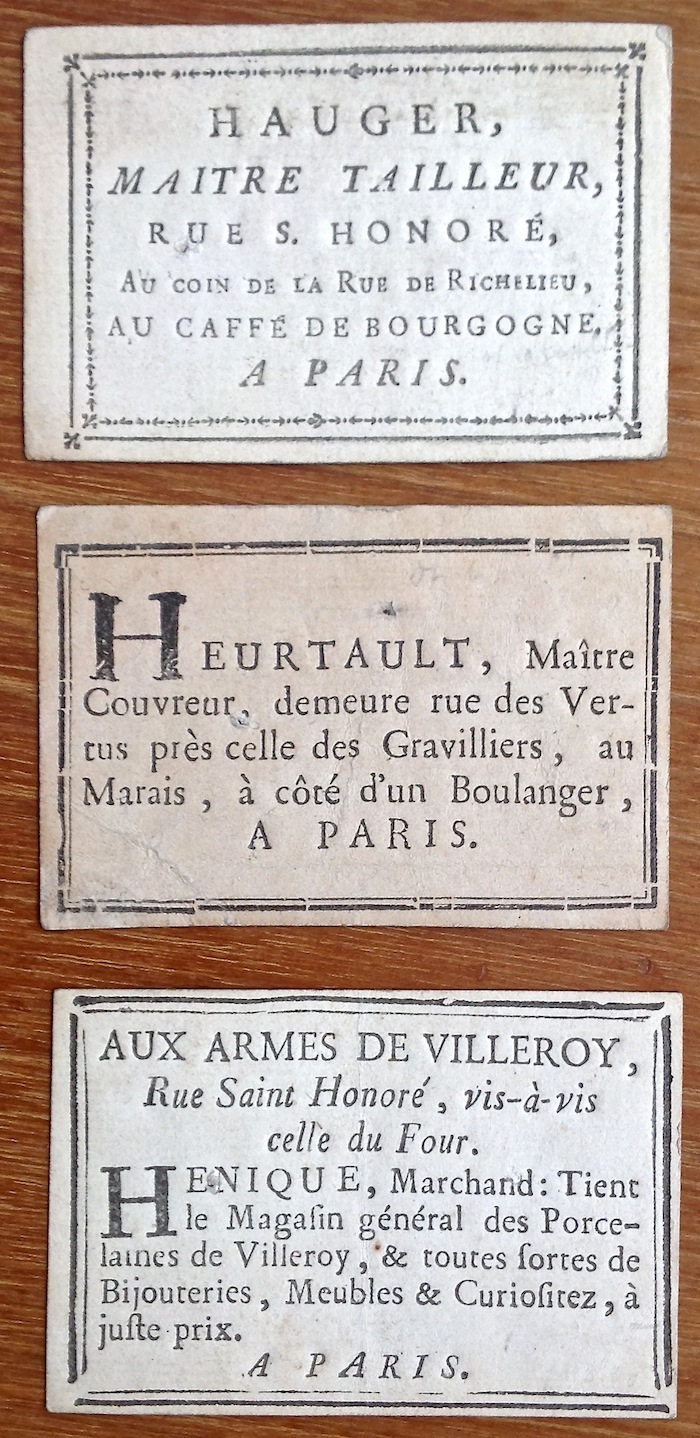

Cards from France, late eighteenth century—reused as business cards: for a tailor, a roofer, and a merchant of general goods.

Cards from France, late eighteenth century—reused as business cards: for a tailor, a roofer, and a merchant of general goods.

A Jack of Hearts from Canada, mid-nineteenth century, cut into three pieces, each repurposed as scrip for a loaf of bread.

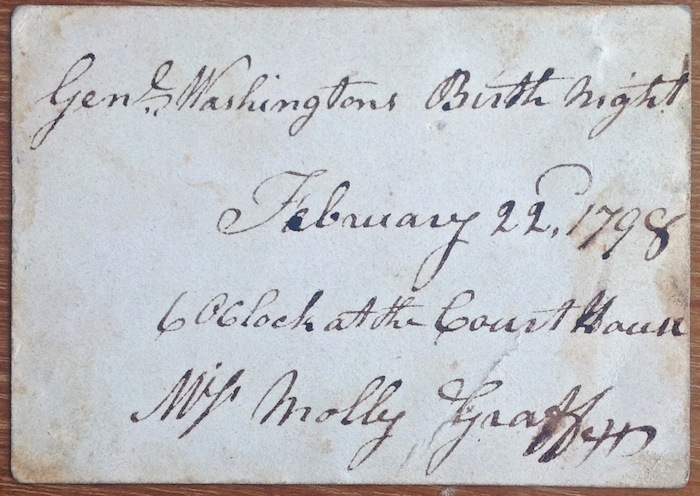

A King of Spades, United States, late eighteenth century, turned into an invitation to a George Washington birth night party—one of the most important social events in the early years of the United States of America.

A King of Spades, United States, late eighteenth century, turned into an invitation to a George Washington birth night party—one of the most important social events in the early years of the United States of America.

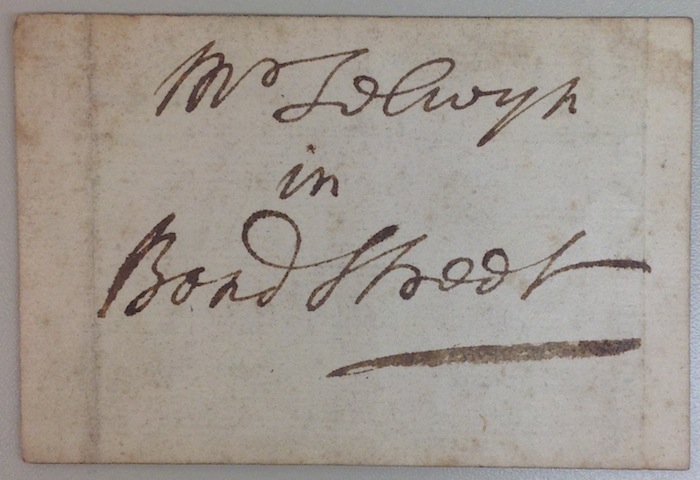

A calling card, England, eighteenth century.

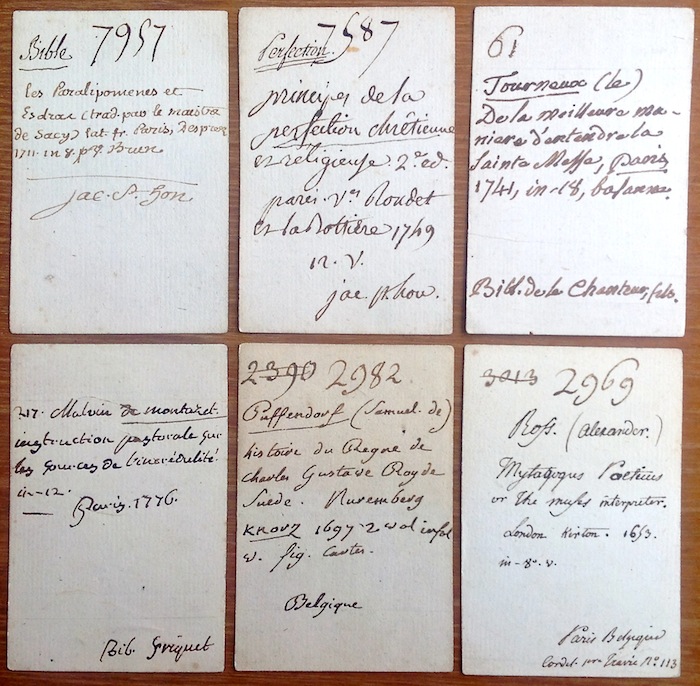

Catalog cards for a library, France, circa 1795.

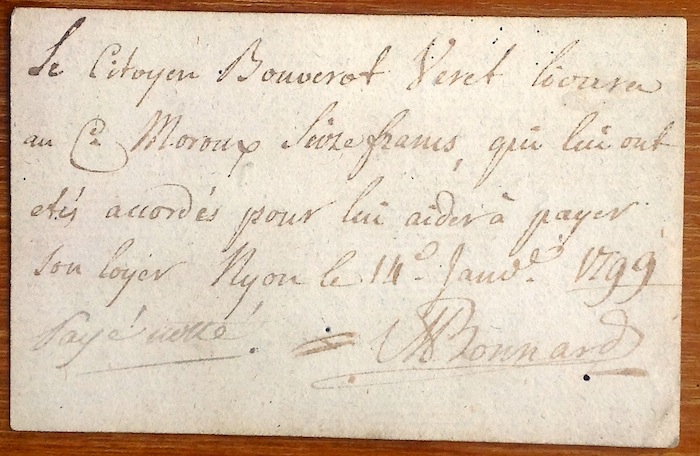

A receipt for a loan, France, mid-eighteenth century.

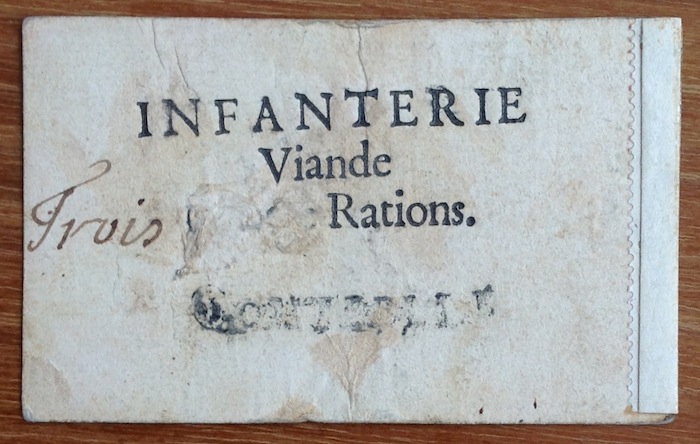

A voucher for army rations, France, eighteenth century.

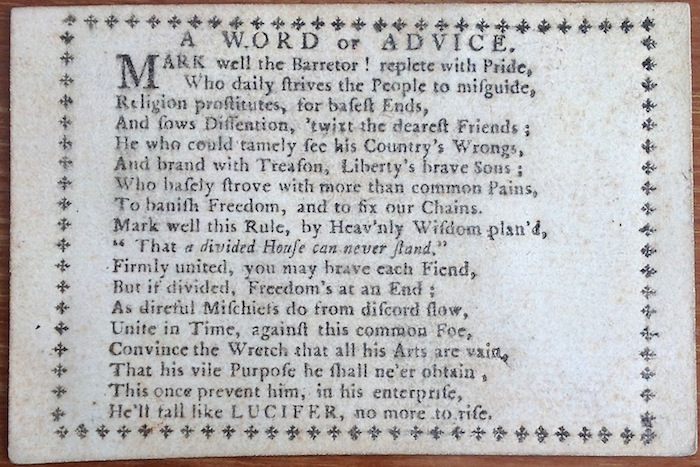

And as a mini-broadside, New York State, 1768 or 1769. This gem was used to print an allegorical poem intended to foment resentment against John Morin Scott, in the wake of the Stamp Act of 1765. This piece appeared in 1768 or 1769 and is attributed to John Holt. The poem also appeared as a larger broadside the same year. The reason it appeared in this form—on the verso of a playing card—may be to intentionally flaunt the terms of the Stamp Act, which included a tax on playing cards. (Disclaimer: This card shows a lot of work and may have been printed specifically for the purpose of disseminating the poem. But it has the look and feel of a repurposed card.)

In a way, all of these cards have become archival: holding a secondary value beyond the reason they were created. They still convey their original graphic intent, but carry specific details that can tell us about they how they lived multiple lives.

All cards shown are in the collection of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale.