1.

Jerome Seckler’s unpublished interview with Matisse is distinctive for its combative tone. Seckler’s questions are direct and often challenging. Matisse is sometimes on the defensive, at other times formidable. They seem to have struck up a jousting but respectful dynamic.

Peppered between the tense clashes, which are mainly at the start of the interview, there are moments of humor. Towards the end Matisse shows his vulnerability when he asks Seckler if he thinks he is neurotic.

This is in contrast to other interviews that Matisse gave around this time, especially for French radio in 1942. The tone in that interview was deferential; Matisse’s replies are abstract and aloof.

2.

In yesterday’s excerpt, Seckler began the interview by probing Matisse’s use of subject matter as a source of inspiration. Seckler had been conducting a series of interviews with other French painters of the time, and he knew this was a point of contention for Matisse.

Seckler pecks away at him, brings up an old quote, and pushes Matisse into saying that that his art should lead the viewer into “a domain that puts him outside of his annoyances,” an argument for art for everyday people, for decoration, for pleasure and repose. Matisse goes on to say that his paintings should please a worker for its own aesthetic sake, as opposed to the appreciation that a banker might show, who sees art primarily in relationship to other art on the market. It’s a prescient statement that might easily apply to the nature of art and its market today.

Matisse goes on to revisit the wounds of past criticisms and proudly, almost boastfully, claims that although he has not always been understood as an artist, he is now being “admitted,” meaning accepted by the art establishment (after years of neglect, the French Government, in 1945, bought seven of his paintings). Seckler’s astute questions give us a glimpse into the insecurities of one of the most important artists of the twentieth century.

In the radio interview, when he was asked generically “Why do you paint, Mr. Matisse?,” he replied generically, “to translate my emotions, the feelings and reactions of my sensibility through color and drawing … ”

In contrast, Seckler’s Brooklyn-born chutzpah got Matisse’s goat. As a result, we have a much more revealing interview. As ee cumings once said, “always the beautiful answer who asks a more beautiful question.”

In part two of the interview, published here, things take a more political turn. Read Part 1 here.

++

Jerome Seckler: If the artist plays such an important role in society, don’t you think that a government subsidy should be paid the painter just like it pays any other government worker? He wouldn’t have to worry about where his next piece of bread was coming from. He could live a normal family life like any other person. He wouldn’t be at the mercy of a dealer. He should really be free to paint.

Henri Matisse: I am against ease. If one leaves the possibilities of getting a pension from the government for painting, to all the people who want to paint, all the Sunday painters will seize a brush. That is impossible. It is necessary that there be a straining. While giving to people who want to paint the facilities of doing it, it is necessary to put up a very strong barrier to prevent the invasion of the bad painter. Each time that a student who devotes himself to painting arrives at school for the first time, he should be given a volley of blows by a stick and after to lead him back to his home and he will see if he wants to begin again. If there was a test like that there would be a great many who would not return.

It is necessary that life be hard in order to form one’s character. That makes muscles. Art is a thing of exception. A great many people think today that they are artists because they see beautiful sunsets, or flowers. Today with the degree of civilization to which we have reached, everybody is sensitive to art, but that doesn’t mean that they are capable of making all that. One would not be able to make anything more if everybody were painting. I speak to you sincerely. I would wish that a commission of recognized artists chose among the young people those gifted to paint and that the State give them a subsidy. But the works produced by these artists must belong to the State, who would put these pictures in its museums, in a fashion that one coming into France would see French painting, in America he would see American painting, etc. This is what would happen. The best painters would be not those who are not recognized by the commission. They are the ones who would arrive all by themselves. You are recognized by the committee of artists. Immediately, you are seated nicely in your chair and you say to yourself, “I am an artist I am recognized.” That gives you pride, pretensions. One must guard in himself the desire to work. Make it secretly, if need be, but make it. One must suffer for what one loves. It is the truth for me, but perhaps not for you.

I tell you what I think. These young people who will be recognized as artists, they will not be among those who will come out the best artists. The best will be those who will have been forgotten because they are not formed to what one wants them to be. Those who will work with their soul and the desire to express themselves and it is these who will come out the best painters.

JS: It seems to me that the more painters there are the better it is. First of all it creates more of an understanding of art among the people. It serves an educational purpose that way. Secondly the more painters there are the more probable it is that there will be more better painters. You can surely get more good apples from an orchard of apple trees than from one tree. If we get only ten good artists, out of 10,000, it’s still better than having one good painter in a thousand. In the United States during the depression, the government created a federal arts program which gave employment to many artists and in addition many art schools for beginners were opened. It proved a tremendous impetus to American painting. Many of our good painters today got their start then. And in mural painting for instance, many public buildings had murals painted in them. Although many were bad it did gain my country the beginning of a tradition in mural painting. Why should an artist have to starve? Why should I be like a rag-picker in society?

HM: You are not a true investigator. You wish to impose your ideas on me. All the artists who began by being hungry and cold have made good painting. Everybody, Picasso, Magritte, Rouault and myself, all began like that. The facts signify something. A true artist works in order to see clearly within himself, to understand himself. One cannot understand a painting who does not know himself. The questions that you pose for me are not very complicated. They are very simple and evident. It is evident that in order to make good artists it is necessary that they not eat too well.

JS: But once you stopped being cold and hungry that didn’t stop you from continuing to develop your art. Speaking of suffering and art many painters have told me that the war for instance has in no way affected their painting.

HM: It is impossible that an artist should not feel the after effects of the war. That makes him take things more profoundly. For what he has to do, that cannot change his work.

JS: The war seems to have had no influence on art in France and I do not understand it.

HM: It should be that one might go to the homes of all the painters. One should go once a week, once a month in all the studios and one should break all the paintings with bottles, one must break the bottle. But the bottle is a bad example. With the same subject one is able to have different expressions, but the bottle is made from Cezanne and that is not good. The people who make bottles are the people who tell themselves, “bottles are very good, since Cezanne has made them.”

JS: When the painter working in his studio, he does not understand what 's going on outside.

HM: A painter is no more the master in his studio than outside. The artist needs to represent things in a frame which corresponds to his feelings. If it is clouds, horses, it is the same law. The artist goes outside. He sees something which enriches him. He re-enters to his home. His objects, the understanding of the object profits from what he has seen. I made a picture, a young girl before a window. I left it in order to go to the pacific islands, to take the boat, to go to New York, a magnificent city, the buildings so big made the blue sky look higher. I crossed America. I have been in Chicago, Los Angeles. I didn’t want to see Niagara Falls because I had seen it too much in photos. I have been to San Francisco. I left for Tahiti. I saw a vegetation completely different, all sorts of things, extremely beautiful and curious. I have been in the atolls where the air is of such purity without any dust. The fish are of all colors. I returned by the Panama Canal, stopped at Martinique and Guadalupe and came back to Marseille. I came back to my studio and looked at my painting again and finished it. Sometime after I made a decoration for Barnes. There I expressed what I had felt during my voyage and I owe to this voyage what I made. It is not the subject which counts.

The subject puts you on the road, but it doesn’t count.

++

Continue to Part III here.

++

This interview is published by permission of Donald Seckler. I'm indebted to Hilary Spurling’s Matisse the Master. The editors would like to thank Marisa Nakasone for her transcription help.

Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs is on view until February 10 at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Images:

Henri Matisse, Composition Green Background (Composition fond vert), 1947. Gouache on paper, cut and pasted, and pencil. 41 x 15 7/8” (104.1 x 40.3 cm). The Menil Collection, Houston. Photograph: Hickey-Robertson, Houston. © 2015 Succession H. Matisse, Paris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

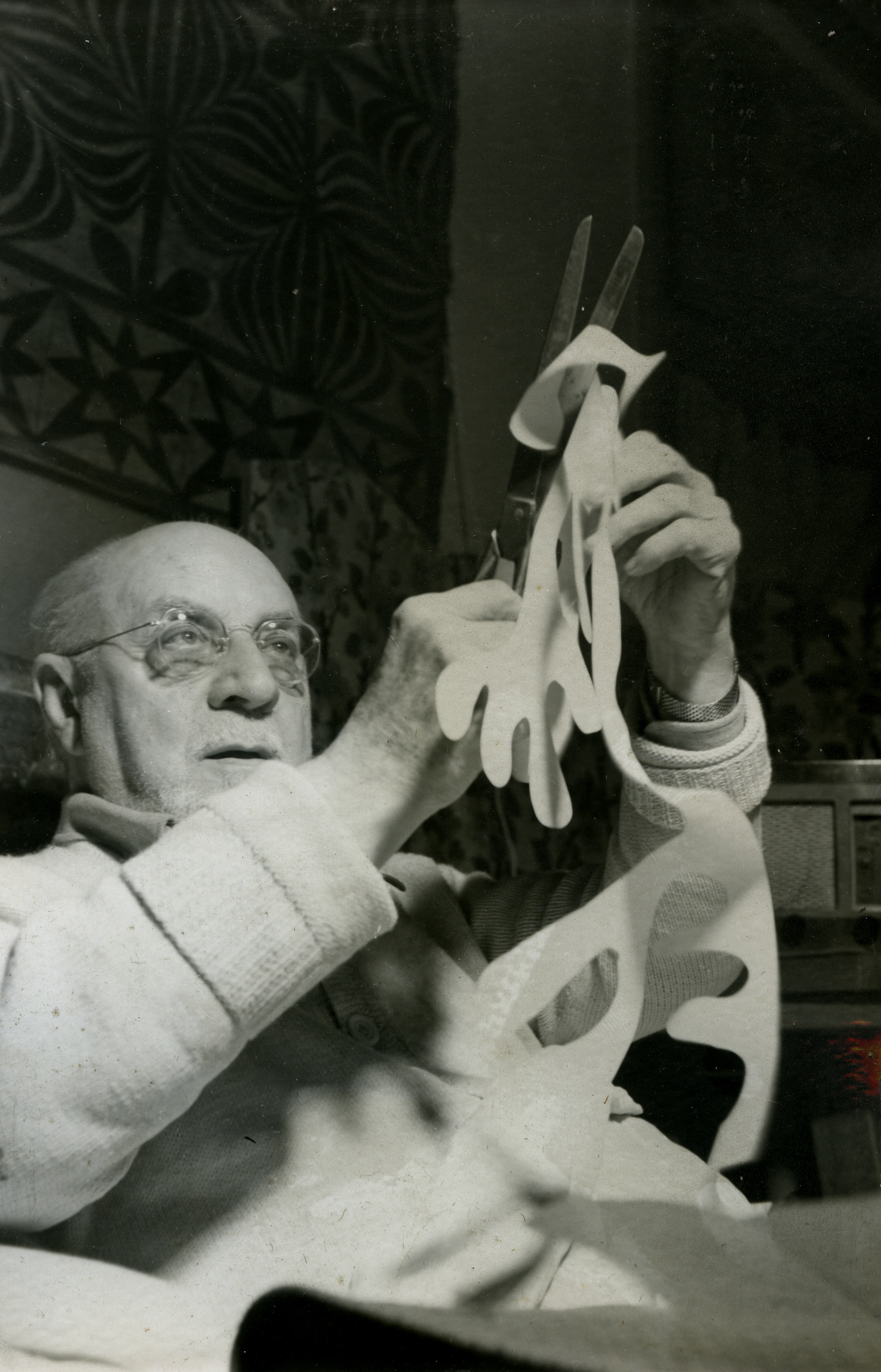

Matisse at Villa le Rêve, Vence, c. 1946-47. La Biennale di Venezia – Archivio Storico delle Arti Contemporanee. Photo by Interfoto

Homepage image: Henri Matisse, Composition, Black and Red (Composition, noir et rouge), 1947. Gouache on paper, cut and pasted. 16 x 20 ¾” (40.6 x 52.7 cm). Davis Museum and Cultural Center, Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA. Gift of Professor and Mrs. John McAndrew. © 2015 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York