The Lion Aslan, the White Rabbit, Mrs. Frisby, Stuart Little … talking animals have always been a feature of children’s books, among the most reliable of story-telling props. From early fairy tales through classics of the twentieth century, quadropeds walk upright, talk, wear glasses, carry pocket watches—all the things that humans do. Aesop populated his stories with wise (and not-so-wise) animals.

Kenneth Grahame may have perfected the human-like animal—giving the world a Toad who not only drives a car, but is frivolous, jealous, fickle—and even cross-dresses. Librarians have examined the role of talking animals and found that children benefit from a sense of distance that allows for some readers to deal with difficult life issues. Yet, a recent study by a team of psychologists asserts that anthropomorphized animals may decrease actual knowledge of the animal world for young children.

Kenneth Grahame may have perfected the human-like animal—giving the world a Toad who not only drives a car, but is frivolous, jealous, fickle—and even cross-dresses. Librarians have examined the role of talking animals and found that children benefit from a sense of distance that allows for some readers to deal with difficult life issues. Yet, a recent study by a team of psychologists asserts that anthropomorphized animals may decrease actual knowledge of the animal world for young children.

But what to think about characters who are not even supposed to be alive? It so happens that, during a particularly enthusiastic period for juvenile literature, objects lacking both motion and appetite (using the ordering principles of The Great Chain of Being) flourished as characters in storybooks. Between roughly 1910 and 1940, a number of books featuring talking trees, golf balls, pianos, candies, and other unlikely characters were unleashed in the fast-growing genre of juvenile books.

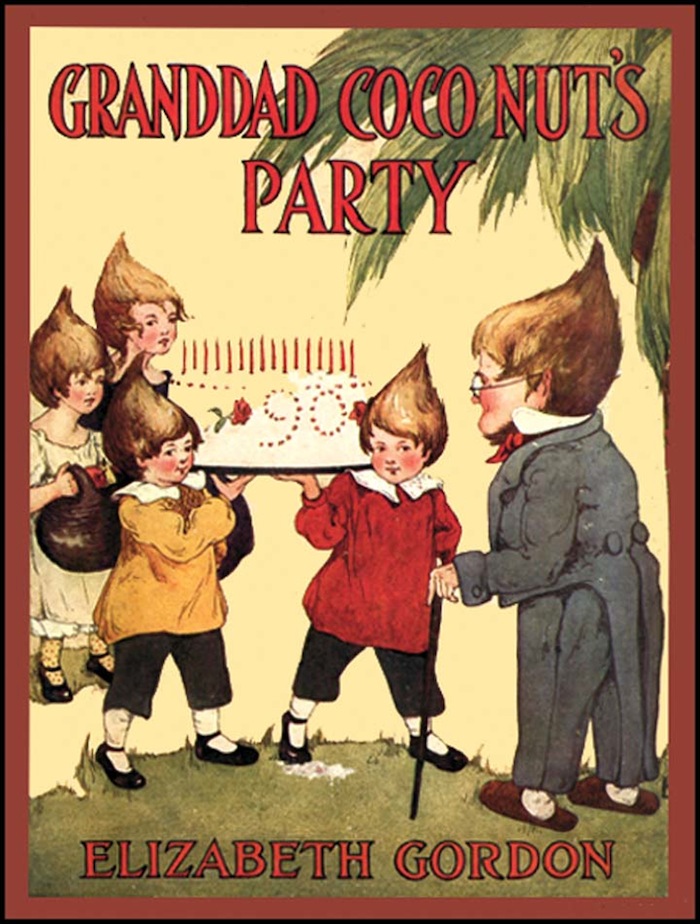

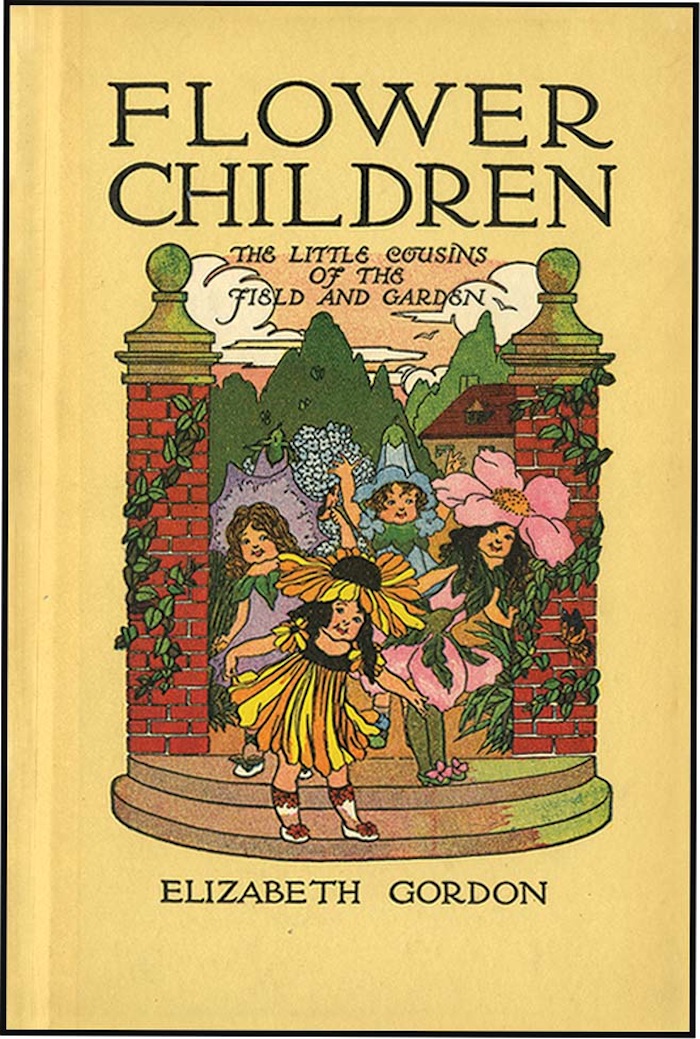

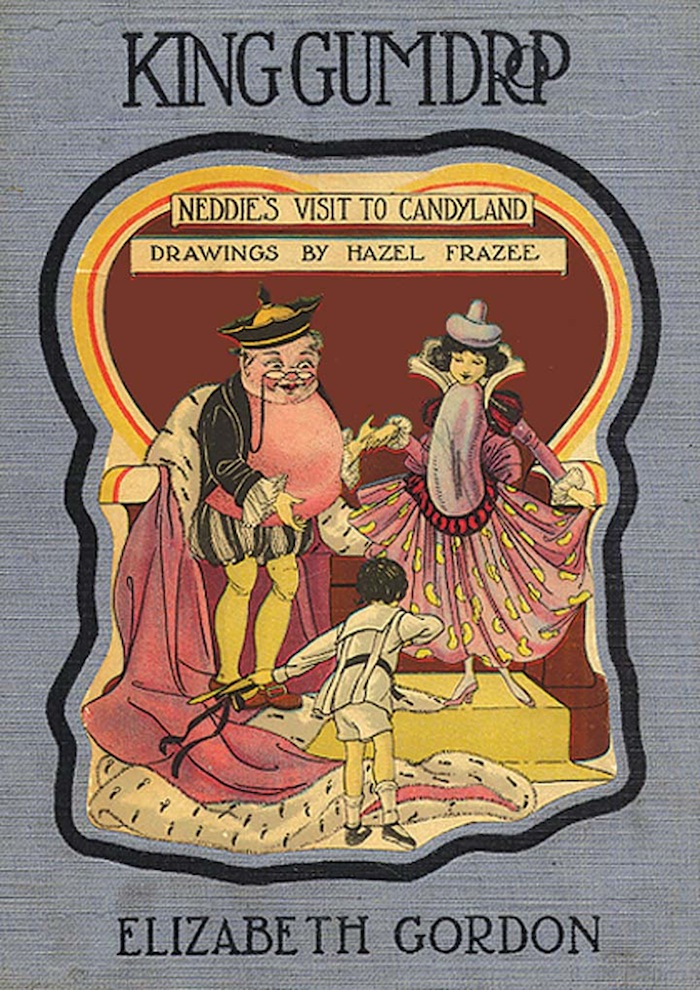

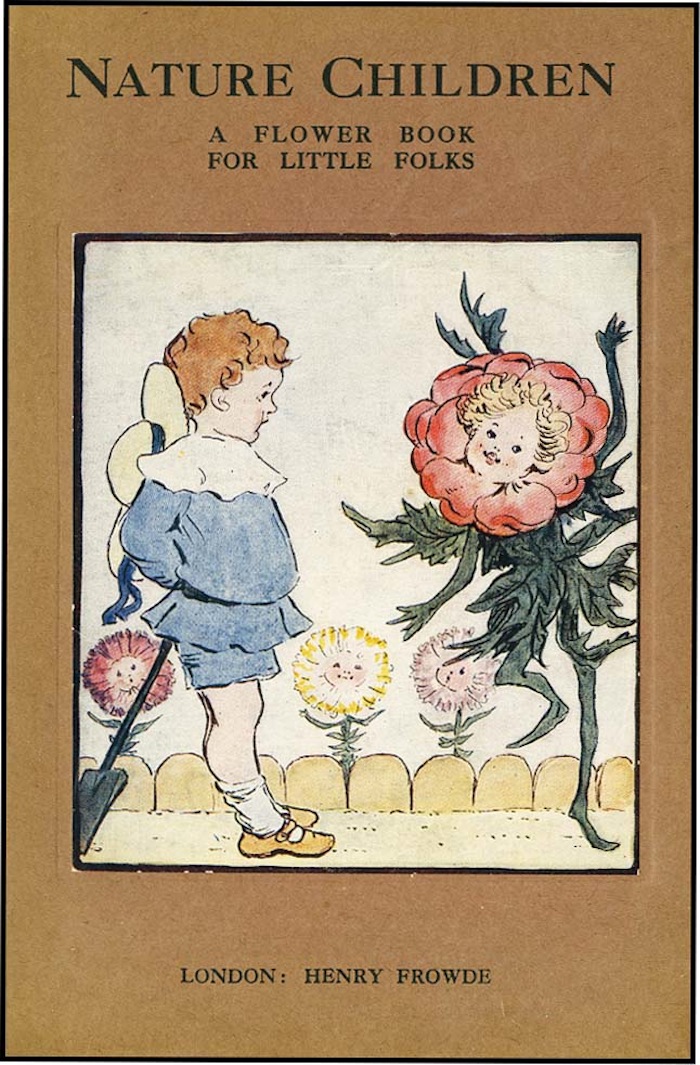

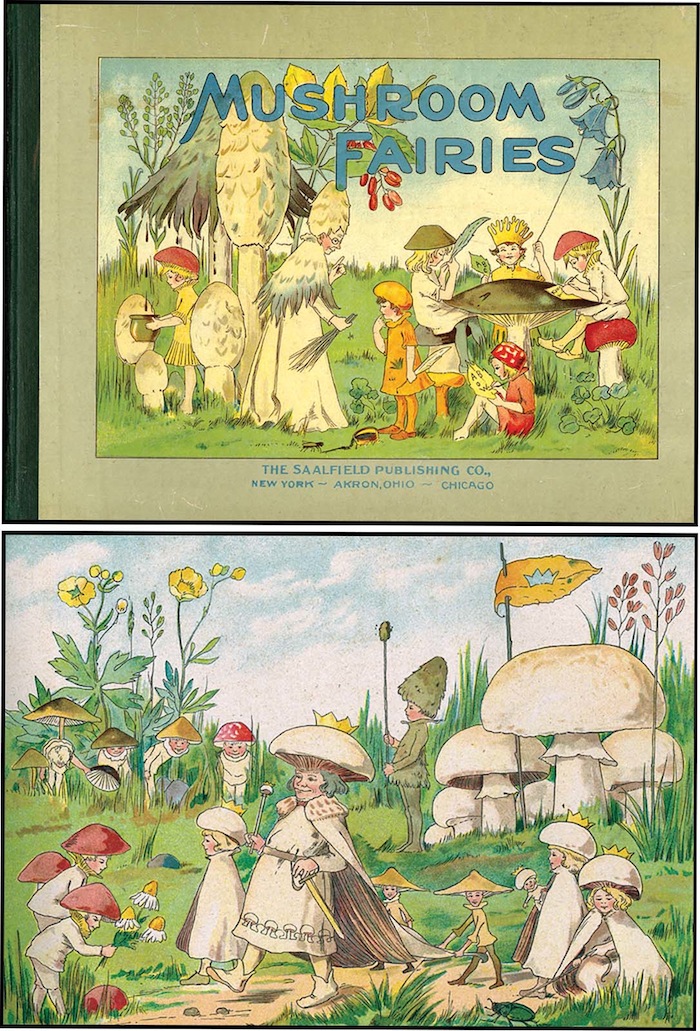

Talking plants, a particularly popular trope, may not be such a stretch for the imagination. A number of books have been built around flowers, including Nature Children: A Flower Book for Little Folks, by Gertrude Faulding (Henry Frowde, 1911) and Flower Children by Elizabeth Gordon (Volland, 1910). Gordon, a writer of popular juvenile titles, produced a sequel, Mother Earth’s Children: The Frolics of the Fruits and Vegetables (Volland, 1914). That same year, everybody’s favorites drupes came to life in another book by her, Granddad Coco Nut’s Party (Rand McNally). In 1916, she continued her divine granting of dynamism to the otherwise consciousness-challenged inhabitants of Candyland in King Gum Drop (Whitman, 1916), and eventually returned to flowers a couple of years later with Wild Flower Children (Volland, 1918). Other edibles got into the action: Mushroom Fairies, by Adah Louise Sutton (Saalfield, 1910) and much later and really stretching the concept to its limits, Bedtime Stories about Cabbages and Peanuts by Harriet Boyd (Saalfield, 1930).

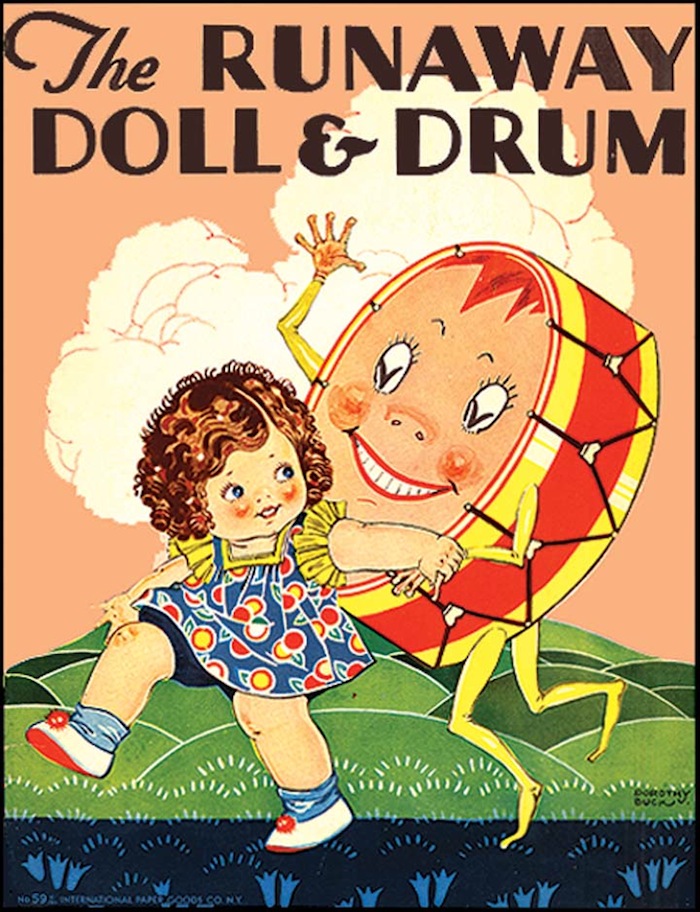

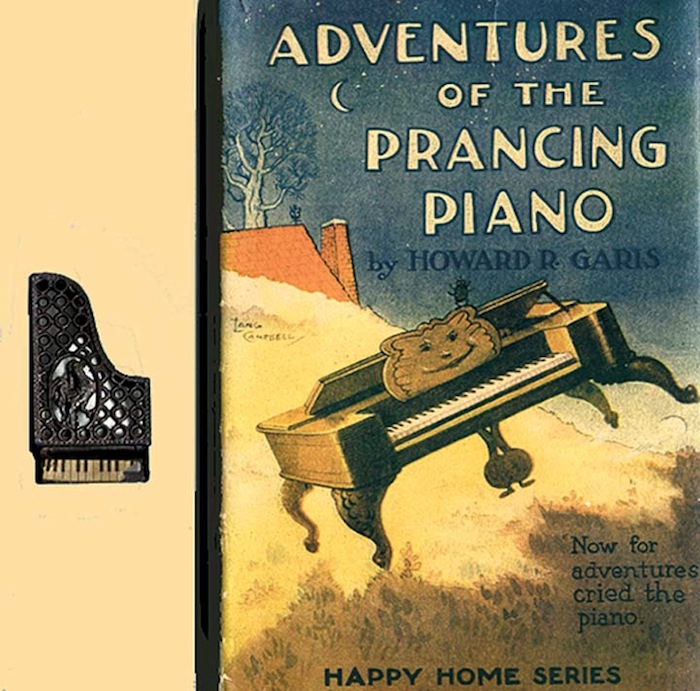

Things get a bit more peculiar when household objects start to spring legs and arms. Witness Runaway Doll & Drum by Bert Delevy (Int'l Paper Goods, 1925) and Adventures of the Prancing Piano (Grosset & Dunlap, 1927) by Howard Garis, best-known as the author of the Uncle Wiggly books. This was the final installment in his The Happy Home Series, which also contained Adventures of the Galloping Gas Stove; Adventures of the Runaway Rocking Chair; Adventures of the Traveling Table; Adventures of the Sliding Foot Stool; and finally—not to leave any furnishing immobilized—Adventures of the Sailing Sofa. The Prancing Piano came in a deluxe version featuring a real miniature piano that talented kiddies could bang away on. (I may be jumping to conclusions, but I venture that there was not a deluxe boxed set that came with a tiny gas stove …)

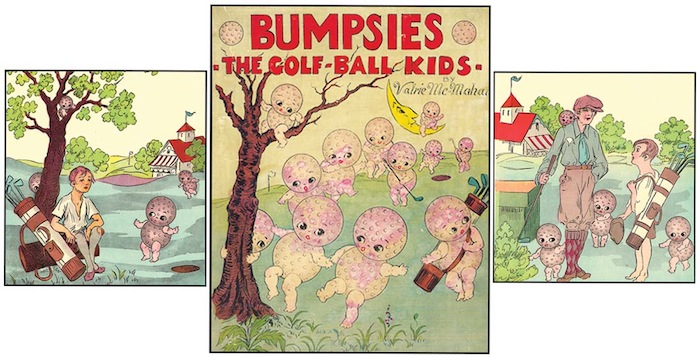

We really plunge into the deep end of the oeuvre when examining the works of by Valrie McMahan: Bumpsies the Golfball Kid and Little Caddie (Roycrofters, 1929) introduced a phalanx of dimpled baby doll golf balls who come to life to teach a young caddie moral lessons—possibly by scaring the bejeezus out of him, Village of the Damned-style.

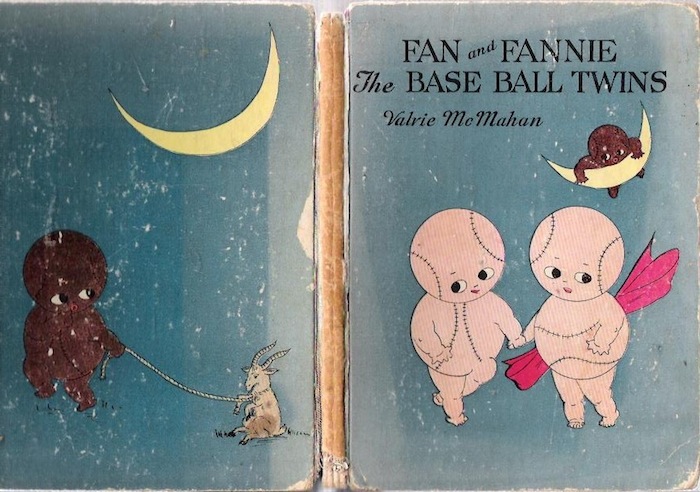

More successful was a series by McMahan featuring Fan, Fannie, Ginger, and Little Stitches, humanized baseballs who appeared in several books: The Baseball Twins (Barse & Company, 1928) and a trio of shaped books: Travel Stories of Fan, Fan-ie, Ginger and Little Stitches (Doll University and Toyland of America, 1932). These characters were apparently successful enough to have been issued as dolls. The Bumps book was published the Roycroft Press, a project of the handcraft community, established by Elbert Hubbard. It is a glaring anomaly in a bibliography that is otherwise dedicated to more pragmatic titles.

So think about these books the next time you roll your eyes while reading your kid a tale of a talking cat or a sassy dog. Would you prefer loquacious lamps and other objects that manifested both motion and, at times, ravenous appetites?

Animated golf balls and rambunctious pianos may have been intended to delight, but to our adult eyes, they can seem pretty creepy. They’re just the type of things that could populate the nightmares of a dedicated adherent of resistentialism, a mock philosophy posited by the British humorist Paul Jennings in the 1940s that asserts that objects are consciously trying to vex us.

Maybe this is what happens as we move from childhood to adulthood—objects become, thankfully, less animated—and less likely to run amok in our books and in our dreams.

All book covers and illustrations courtesy of Aleph-Bet Books, a reliable source for rare children’s books