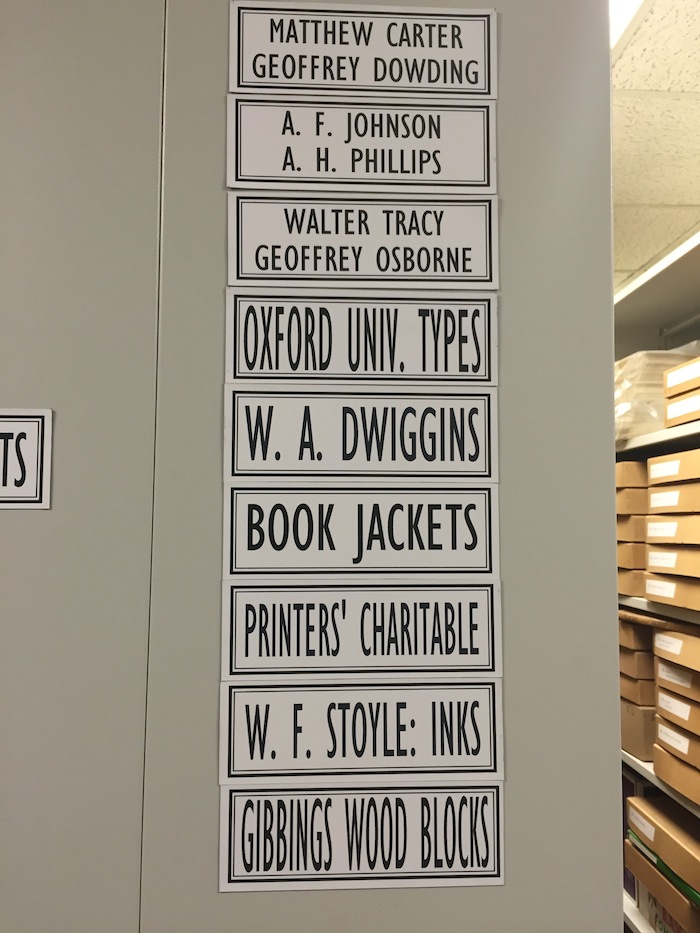

Some collections in the St. Bride Library

If it's crucial to know about history of typography, it serves to reason that anyone working in design should become acquainted with the St. Bride Foundation. In the City of London, off Fleet Street and close by Blackfriars Bridge, stands a collection of nineteenth-century buildings that contain crucial documentation about printing technology and the development of modern typography.

The St. Bride Foundation was established in 1891 to serve as a social venue for members of the publishing and printing trades that had colonized Fleet Street, a long avenue that had already become synonymous with journalism. A suite of buildings was erected to provide gathering spaces—including a swimming pool—for tradesmen and apprentices. A printing school was established and then moved offsite in 1922 when it became the London College of Printing. Letterpress printing returned to St. Bride four years ago when the Foundation’s small museum of vintage presses was opened as a workshop for students.

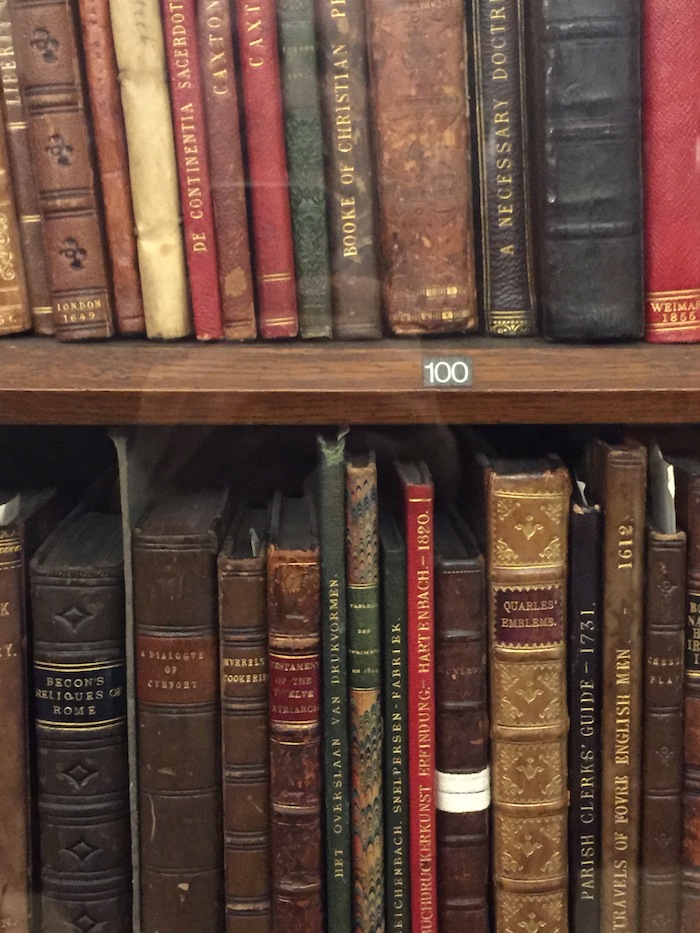

In 1895, a library devoted to the history of printing was opened, and this resource—like so many other libraries—has been the active heart of the institution ever since. The great founding collection came from William Blades, a successful printer who passed away just before the library opened. His library, purchased from his widow, was installed in cabinetry transferred from the Blades house to a customized room at St. Bride. Over the past 120 years, more volumes have been acquired, largely by gift, totalling more than 60,000 books on printing and typography history.

A selection of Blades' books on typography

A selection of Blades' books on typographyOver the past half-century, the collection at St. Bride was expanded greatly by dedicated librarians, principally William Turner Berry, and latterly James Mosley, who brought in examples of letterforms in many manifestations: road markers, enamel house numbers, wooden business signs. Mosley’s influence shifted the focus of the collections and he assembled impressive holdings of original materials related to the history of type founding. The closest peer institution documenting the history of printing is the Type Archive at Stockwell. Archival material was actively sought to complement the books. One of the largest concentrations of Eric Gill's archives are housed in the St. Bride Library, including his original drawings for Gill Sans and rubbings he made from his own inscriptional works. (For practical reasons, the library hasn't made a significant effort to document digital typography, as doing so would require entirely new systems for acquisition and access.)

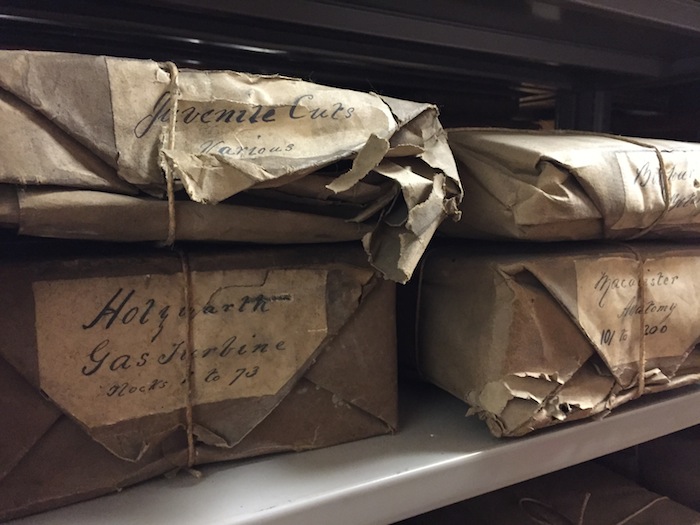

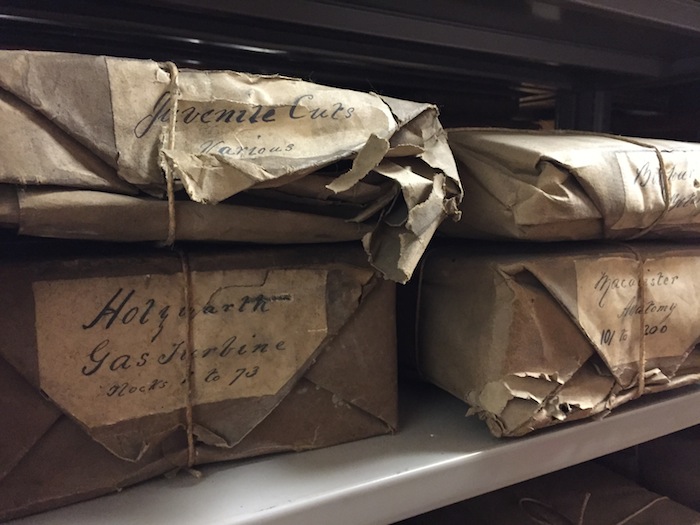

Packages of woodblocks for printing images

Patrons of the St. Bride Library include graphic designers, students, family historians (whose genealogy includes printers), researchers in economic and labor history, and general enthusiasts. To become a registered reader costs £5—less than a single round-trip on the Underground. Tours are provided for small groups. The upkeep of the Foundation relies, therefore, on donations, volunteer labor, and charges for using their evocative spaces for events. The old swimming pool in the basement has been covered by a stage and is now known as the Bridewell Theatre, used by a number of drama and musical companies, bringing in some much-needed income.

I was shown the collections by Bob Richardson, a retired graphic designer who began volunteering in 2012 and who now devotes as many as four ten-hour days a week to the Foundation, serving as pressmaster and (since he had been a library user for decades) the institutional memory. Heather Jardine donates her time as resident librarian, organizing and overseeing the cataloging of the collection. Retired librarian James Mosley continues as an invaluable source of information relating to the collections. The library’s collection can be searched via the Guildhall Library catalog.

Every shelf reveals a resource for learning about printing and type design—steel letter punches for Caslon faces, copper matrices, the lavish decorated alphabet blocks of John Louis Pouchée (unique to St. Bride), litho stones, and printing presses. The building’s floors are reinforced to hold 1 ton per square yard—sufficient to support the collections, presses, and full metal typecases.

Boxes of letter punches in Caslon type

Decorated alphabet blocks by John Louis Pouchée

Copper matrices for casting type

Despite these riches, the Library has been closed since December 2014. The reason is bluntly practical. In the historic center of London, buildings tend to be fitted close together. The St. Bride Foundation shares a common wall with its neighbor, Fleet House, which is scheduled to be demolished sometime in the next year. The planned pile-driving and heavy-duty construction for the skyscraper that will take Fleet House’s place will generate vibrations, noise, and dust, and will make for an uncomfortable period for readers and staff, not to mention its unique collections.

Despite these riches, the Library has been closed since December 2014. The reason is bluntly practical. In the historic center of London, buildings tend to be fitted close together. The St. Bride Foundation shares a common wall with its neighbor, Fleet House, which is scheduled to be demolished sometime in the next year. The planned pile-driving and heavy-duty construction for the skyscraper that will take Fleet House’s place will generate vibrations, noise, and dust, and will make for an uncomfortable period for readers and staff, not to mention its unique collections.

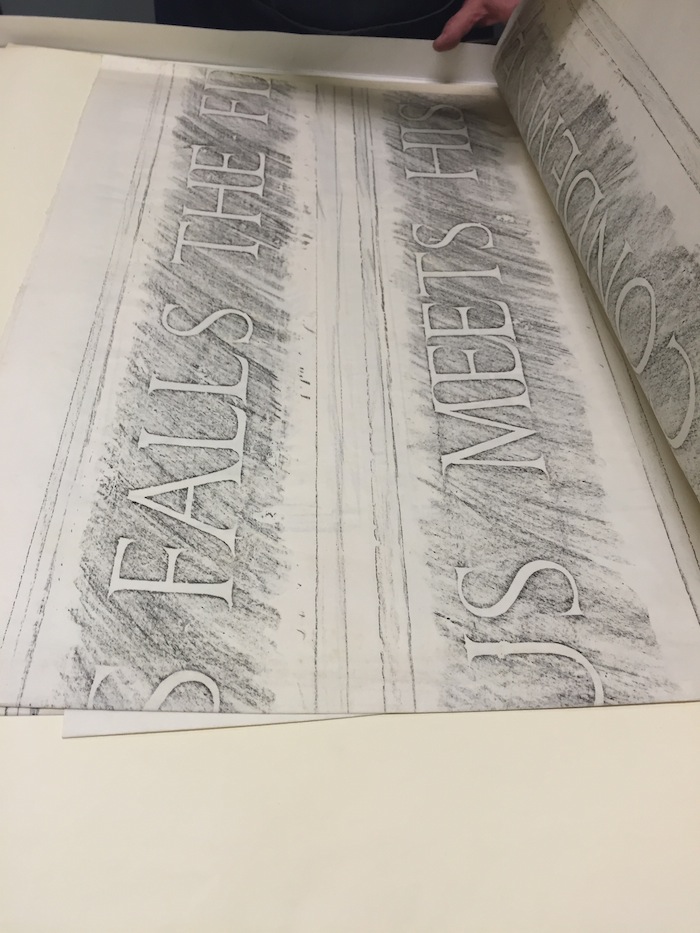

Rubbings from grave inscriptions by Eric Gill

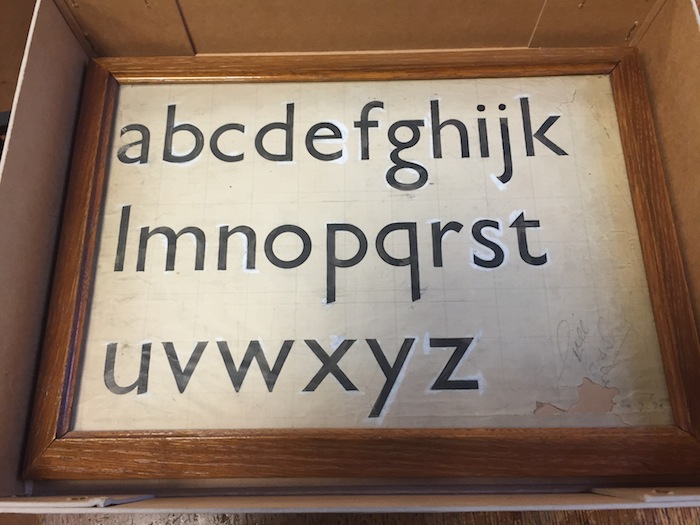

The original handpainted letters for Gill Sans lower case

As of this writing, a firm schedule has not yet been set. Sometime in the second half of 2015, the ground around Bride Lane will begin to shake. An executive decision was made to close the library, though researchers who had already made plans for visits are still being accommodated through the summer. Afterward, some of the more fragile collections will be packed for storage off-site.

This massive disruption is being addressed, and reparations will be made to the St. Bride Foundation—hopefully enough to rebuild and expand the original buildings so that the Library can reopen in a few years in better condition than ever. However, that all remains to be seen.

As Bob Richardson says, with a printer's optimism in his voice, St. Bride will "reopen as a better library with improved facilities." Its absence, though, however brief in the scheme of history, will be felt in the printing history and graphic design community.