Dying is easy, comedy is hard, they say, yet in the so-called comédie humaine, being forgotten is even harder on the psyche. Imagine being at the top of your design or illustration career one minute and entirely below the radar the next. The constant influx of great new design and illustration talent, and the ascent of younger art and creative directors, increases the likelihood of older practitioners being overlooked. Decades ago, I was a dismisser.

As a twenty-four-year-old art director of the New York Times OpEd page in 1974, I was the go-to person for illustration review and acquisition. I could help build a career by publishing a newcomer’s work and revive a career, if temporarily, by re-introducing a veteran in the Times’ pages. Both were exciting responsibilities. But there was another, less pleasurable, role.

Many illustrious designers and illustrators, owing to circumstance, had lost sinecure in their respective media outlets. Time may have taken its toll on their styles. Or their ideas were just no longer as sharp. Any number of reasons accounted for pedestals falling and careers breaking.

My own profound lack of experience and knowledge of history made me insecure, yet brash, which led to having little patience with the old-timers who came around. They had their chance, now it was my generation’s turn. Only later, when I became a student of design and illustration history, did I realize how idiotic that was.

When I began at the Times many venerated illustrators like Andre Francois, Roland Topor, and Ronald Searle were represented by John Locke, an agent who made certain that snot-nosed art directors like me understood these artists’ place in the pantheon. But there were many others of similar stature who were not as fortunate to have such an advocate.

I recall one in particular, a Czech-born German cartoonist, Oscar Berger, to whom I owe an apology.

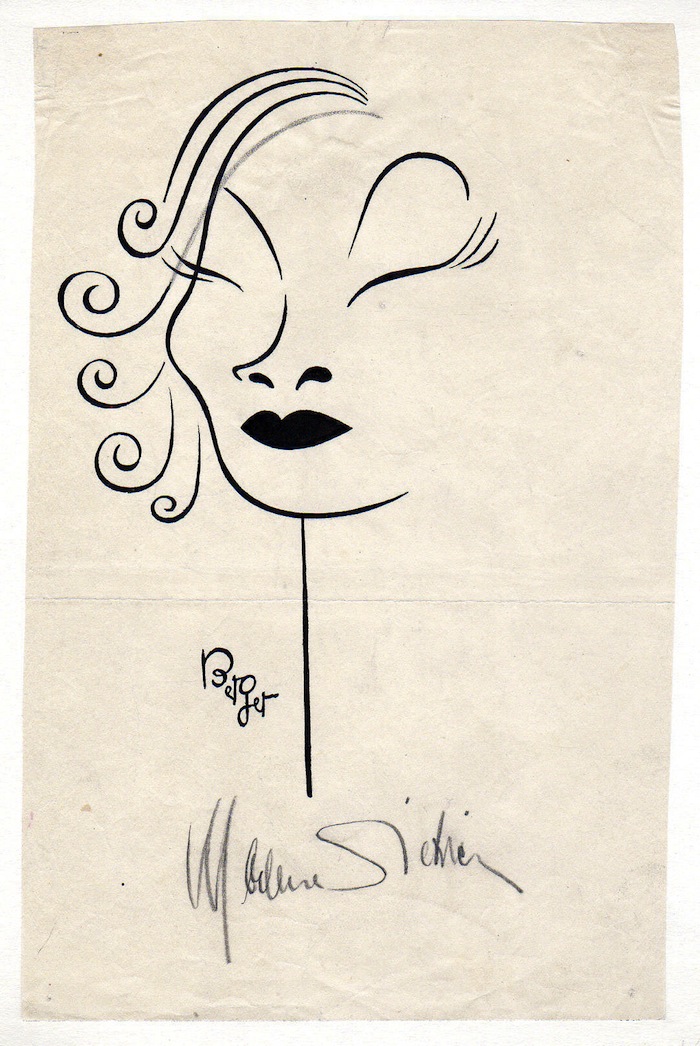

Oscar Berger, Marlene Dietrich | c. 1952

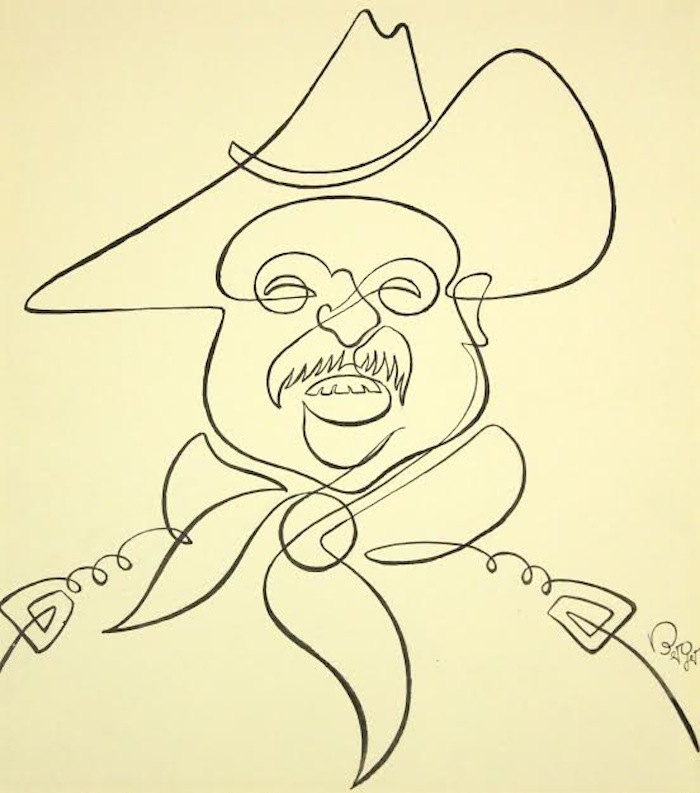

Berger was a nuisance, I thought, routinely sending me work and stopping by without appointments to get work, which I didn’t have to give him. I was dismissive, even rude. Little did I know until I began researching Weimar-era German satiric and comic magazines, that Berger (1901–1977) was a prolific political cartoonist in Germany, whose work appeared in many of the top magazines. He was one of the few artists allowed to cover Hitler’s Munich Putsch trial in 1923 and was known for his theatrical caricatures. He left Berlin in 1933 when Hitler came to power, following the oft trodden émigré’s path through Prague, Budapest, Geneva, and Paris before settling, in 1935, in London, where he contributed to The Daily Telegraph, Lilliput, Courier, and News of the World. He also produced posters and advertising for Shell, London Transport, and the Post Office. He was a roving visual journalist and was often drawing diplomats and world leaders at the United Nations. In the 1950s, he immigrated to New York, where he published a book on caricature, yet work was harder to come by and his reputation in Europe meant little here.

Berger was a nuisance, I thought, routinely sending me work and stopping by without appointments to get work, which I didn’t have to give him. I was dismissive, even rude. Little did I know until I began researching Weimar-era German satiric and comic magazines, that Berger (1901–1977) was a prolific political cartoonist in Germany, whose work appeared in many of the top magazines. He was one of the few artists allowed to cover Hitler’s Munich Putsch trial in 1923 and was known for his theatrical caricatures. He left Berlin in 1933 when Hitler came to power, following the oft trodden émigré’s path through Prague, Budapest, Geneva, and Paris before settling, in 1935, in London, where he contributed to The Daily Telegraph, Lilliput, Courier, and News of the World. He also produced posters and advertising for Shell, London Transport, and the Post Office. He was a roving visual journalist and was often drawing diplomats and world leaders at the United Nations. In the 1950s, he immigrated to New York, where he published a book on caricature, yet work was harder to come by and his reputation in Europe meant little here.

Berger was just the kind of person that right this minute I would want to spend a lot of time with listening to stories and capturing them on tape as oral history. He worked with many of those I considered masters, and he was considered at the time to be among that group. But other than a curt hello/goodbye I hardly exchanged words when I had the chance—and did not give him any work (although one of my colleagues would offer a spot now and then).

Oscar Berger, Theodore Roosevelt | 1968

I often fantasized about meeting some of the heroic émigré masters, notably George Grosz, and asked myself whether I would give them work or not. Little did I know the answer was staring me in the face.

There were other displaced artists and designers who came through my doors on portfolio mornings, and some of them later turned out to be important enough to be written about in design histories. That they went on portfolio reviews was itself an indication of how easy it was to lose footing in this field.

A few years into my job, I knew the blinders had to come off. Not because I was becoming a writer of design and illustration history, but because it was the humane thing to do. I realized that a few decades later I could be Oscar. It's easy to fall on hard times and never revcover. Conversely, take Alex Steinweiss, who I helped to resurrect in the 1990s, and who did well enough in his life to enjoy his “forced” retirement. But there are other designers, illustrators, and photographers, as we learned in Adam Harrison Levy’s touching Design Observer story on William Helburn, who did not fare so well in his later years. After having an incredible early career, falling into the void is much easier than simply dying—and that ain’t no joke.