Designers are a “nightmare to survey,” according to the sociologist Nikandre Kopcke. She should know, she’s helped to formulate the questions and evaluate the results of an in-depth survey of nearly 2000 UK and USA graphic designers. According to Kopcke, designers “frequently disregard instructions and give answers that can best be described, fittingly, as creative.“ I recognize that description. It’s one I’ve had thrown at me by numerous clients over the years.

The results of this “nightmare” survey can be found in a chunky little book published by GraphicDesign& called Graphic Designers Surveyed. The book is edited by Lucienne Roberts and Rebecca Wright, two of the sharpest brains on the UK design scene, and founders of the GraphicDesign& imprint. Roberts is a designer with a strong social bias in her work, and Wright is a prominent educator. Together they formed their publishing house to create “intelligent, vivid books that explore how graphic design connects with all other things and the value that it brings.”

In their introduction to Graphic Designers Surveyed, Roberts and Wright state the purpose of their survey: “… we wanted to know about the people behind the work—who we are and what we do.” Drawing on Kopcke’s expetise, they devised a questionnaire modelled on social science techniques that enquired about such subjects as age, gender, ethnicity, income, and the craft and professional practice of graphic design.

The results make fascinating reading, although the accumulated findings throw up as many questions as answers. The most salient of which is how were designers chosen for the survey? “Respondents were self-selecting,” claim the editors. The questionnaire was circulated virally in early 2015 and was featured in both UK- and US-based design-orientated websites. Design agencies and personal contacts were also emailed and Twitter was used to spread the word.

The relatively small number of individuals polled inevitably prompts the reader to question the validity of the findings. A total of 1,988 graphic designers completed the form (68% in the UK; 32% in the US). This is not an insignificant number, yet when compared with the actual number of graphic designers working in the US (197,540 in 2014), only 0.3% of the total number of American designers is represented.

But given the care with which the questions are framed, the outcome has an integrity that is hard to argue with. And as both a graphic designer and someone who filled in the form, I find the responses credible and chime with my own far from exacting reading of the design scenes in both countries.

The most interesting aspect of this survey, to me at least, is how UK designers compare with US designers. Summarizing the statistics, Kopcke writes: “ … designers in the UK felt less satisfied with their work life than designers in the US. Financial security was more of an issue for UK-based designers, especially the lowest-earning ones [though women in both groups were more satisfied than men.]”

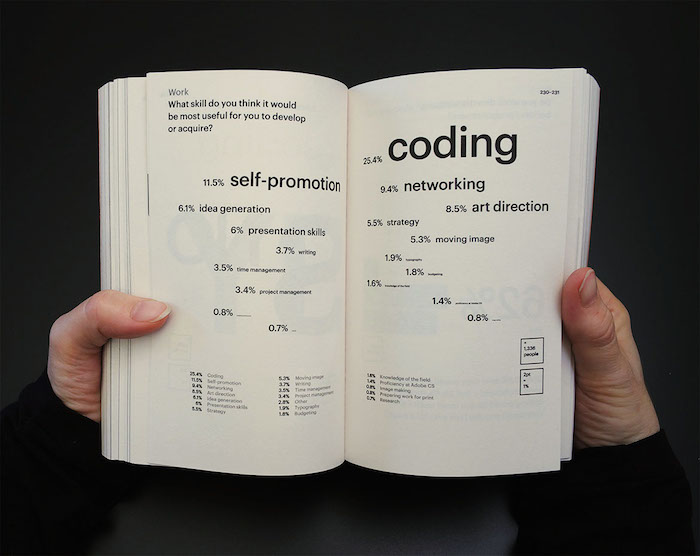

UK respondents reported a higher level of academic achievement than those in the US. In the under 40-age group, UK earnings are lower than in the US. American designers work longer hours than their British counterparts, but both groups (UK 81%; US 71%) acknowledge that they work more hours than they are paid for. Ouch. I recognize the veracity of that statement, too.

Most of the other categories—ranging from gender to education, from clients to money—uncover a remarkable uniformity between UK and US designers. Even in political affiliations, a liberal consensus prevails in both countries. In the UK, 82% claim support for Labour, Liberal Democrat, and Green parties. In the US, 81% cite allegiance to the Democratic and Green parties.

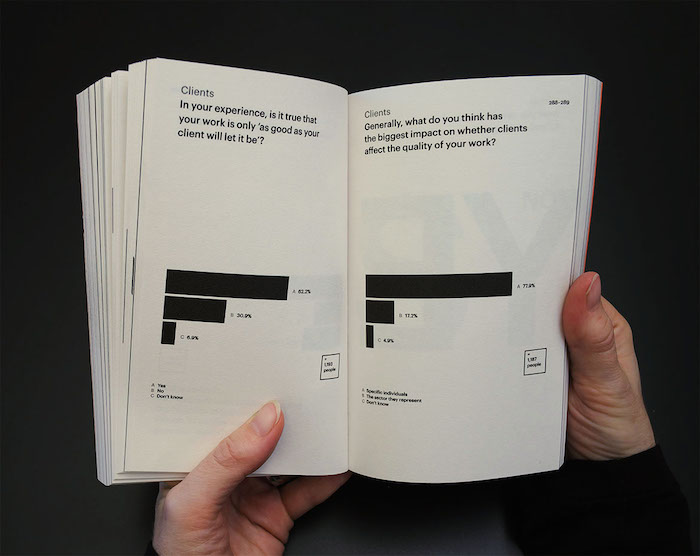

A section titled Worst/Best provides a list of verbatim statements drawn from the questionnaire. This further confirms the similarities between the two countries. Anyone familiar with graphic designers will recognise the views expressed here. It is a recitation of common gripes – uncaring clients and dismissive senior staff mostly—set against the joy of making and the pleasure of creative endeavor. Perhaps non-designers will find this stuff interesting, but it is unlikely to cause any epiphanies among designers.

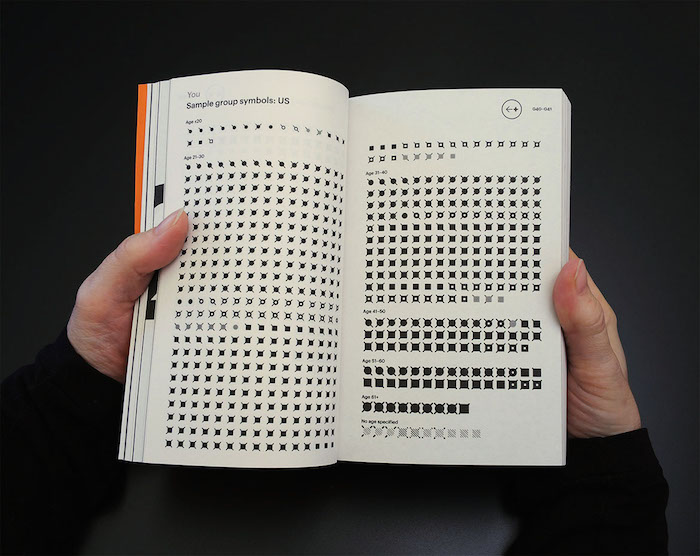

Which brings us to the big question hanging over this project: Why a book? Roberts and Wright are to be congratulated on the dedication and academic rigor they have brought to the task of collating, tabulating, and publishing this data. It feels like a vast undertaking. The book is intelligently designed by Roberts’ studio, and the modest format, utilitarian paper stock, and low retail price are perfectly suited to the material. But the thought lingers that perhaps this is material that would be better presented online?

I hope Roberts and Wright continue to monitor the flux and vagaries of the profession. An online home would allow statistics to be updated and debated, and who knows, designers might even get good at surveys!

Graphic Designers Surveyed is published by GraphicDesign& and designed by LucienneRoberts+ and edited by Lucienne Roberts, Rebecca Wright and Jessie Price. Photos by David Shaw.