Lyric book from Peter Blegvad and Andy Partridge's album Gonwards

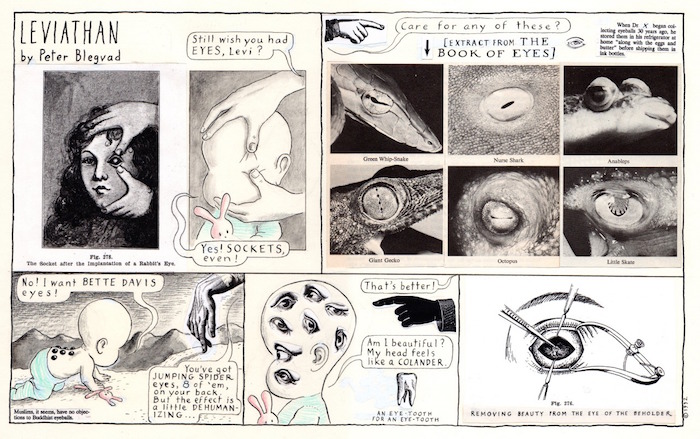

When I met Peter Blegvad decades ago, he was making children’s book and editorial illustrations. Little did I imagine that he would soon become an innovative comics artist in the UK, aclaimed for his popular weekly Leviathan strip about Levi, a faceless baby who crawls through a surreal landscape filled with disjointed words and objects, much like we all do. It became a hit among an adult audience who related to Levi’s existential over- and underpinnings. Even more surprising, was when I stumbled onto his music. Blegvad is a maestro of word, sound and picture – a song writer, singer and player. One of his recent albums Gonwards is an opus of music and, in the deluxe edition, design thinking. I thought it was time to ask him about the cacophony of media that form his body of remarkable work.

To read the complete interview buy a copy of Observer Quarterly 1: The Acoustic Issue.

++++

Steven Heller: I've known you for almost thirty years – if sending letters and now emails back and forth can be considered knowing you – but our acquaintance began with you as an illustrator/cartoonist not as a musician. So, when did these two art forms converge and why?

Peter Blegvad: I think you gave me my first NYT assignment in 1976 or so, almost 40 years ago, would you believe? (It was a drawing of a skeleton in a desert meant to represent NYC's fiscal crisis).

In 1975 I'd come from London to New York City to try my luck as a freelance illustrator, (as my father, Erik Blegvad, had done 25 years before). I was just starting as an illustrator, but I'd already been writing songs, recording (four or five albums) and performing for a few years with Slapp Happy, Faust and Henry Cow in Germany and England. And I was always drawing, recreationally, as a form of thinking or dreaming. Like many pop musicians, I'd been to art school, an environment where visual, musical and literary creativity mingle and crossbreed.

I began playing the guitar, my friends and I formed bands. But some of us were also drawing guitars and bands. I was also drawing surreal fantasies influenced by Bob Dylan's lyrics on Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde and by other stuff I was reading, looking at and listening to. Drawing, writing and music went hand in hand in hand from then on. They didn't seem to contradict each other, working in one mode stimulated my appetite for the others. They all exercised the same psychic muscle: the imagination.

SH: You've been an expat living in England most of your life. Isn't that the reverse way to make an art and music career? Indeed was a career even your goal?

PB: I went through patches of wanting and trying to have a successful music career, willing to prostitute myself, but I lacked other qualifications. Overall, the “career” aspect of creativity wasn't so crucial to me. I was and am an amateur, with uncommercial surrealist tendencies. I wanted to use my practice experimentally as a kind of alchemy, the goal being to transform consciousness, to change my mind. It's a lifetime project.

SH: You're not a Sunday cartoonist or a Saturday musician. You are a pro. You've been part of many groups, including Slapp Happy and Henry Cow, you've worked solo and recently with Andy Partridge. Your comic Leviathan was big in the UK and, may I say, your comics are hilarious and your drawing is impeccable. How do these disciplines balance out?

PB: There were times when making music, meeting cartoon deadlines and other obligations (I've also taught part-time for the past 20 years) felt a bit overwhelming, but they were rare. If we wanted to go on a family holiday for a couple of weeks, I'd have to get a couple weeks ahead with the strip (Leviathan was a weekly). Which meant working round the clock for a while. And as a musician, doing little tours on my own, it was sometimes awkward having to draw the strip in hotels or crash pads with limited drawing equipment and send the finished strips back to London by courier (this was before the interweb). But it was stimulating, too. Constraints are liberating. And having endured long periods of unemployment, it felt good to be busy in those days.

SH: So, now, how do they intersect?

PB: Drawing literally intersected with music when I was touring because some of the songs I used to perform were illustrated by projected slides. Further back, in 1977, with John Greaves and Lisa Herman, I'd written lyrics that were symbiotically involved with illustrations on the album sleeve, for Kew. Rhone. ["One of the few rock albums I'd consider genuinely surrealist in spirit and composition," said Andrew Joron.] A whole book about this strange “interactive” record was recently published by Uniformbooks in the UK, fully illustrated by myself and nicely designed by Colin Sackett. Over the years I've explored other ways of bringing music, images and texts together, including a performance piece ('On Imaginary Media') with actors, projected slides and live music, and, with my cohorts from Slapp Happy, a TV opera called 'Camera' for Channel 4. With new media, the visual, audial and verbal are converging more and more. Soon the gesamtkunstwerk will be everyone's default medium.

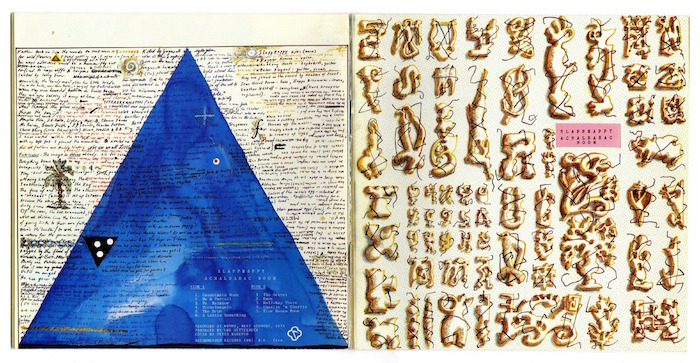

The sleeve for the Slapp Happy album Acnalbasac Noom

The sleeve for the Slapp Happy album Acnalbasac Noom SH: I perceive some of your work as highly experimental with discordant sonics and abstract lyrics. While some of the work, like Sacred Objects, is almost folk. What determines your direction? Is it the context (i.e. the band) is it mood (i.e. your emotions) or something else?

PB: On Gonwards, working with Andy Partridge (who's fluent in a wide range of styles or genres) we could jump from folk to ersatz Russian, spaghetti western, schmaltz, blues, calypso to musique concrete as the mood took us (as long as the music seemed to suit the lyric). Fans of XTC will recognize the music on Gonwards as Andy's work. Both he and I like abstract and figurative art equally. We like sense and nonsense in literature. In music we like harmony and melody, but we like dissonance too. Not to mention environmental noises. As John Cage taught us long ago, it's all music.

A page from Blegvad's well-known Leviathan comic

SH: Let's get back to comics. Your sense of design is acute and astute. From where does this derive?

Poring over those illustration books as a kid; watching my father's work evolve from roughs to print; that was educational.

The style inculcated in me was a kind of old-world classical style – pen and ink, cross-hatching, atmospheric, with handsome serif lettering. I marveled over the engravings in Athanasius Kircher's strange books; Piranesi's “Prisons”; the symbolic illustrations in books about alchemy. I loved Thomas Bewick's wood engravings; The Douannier Rousseau; Outsider art; Max Ernst's collages. The comics I liked included the usual suspects: Pogo, Peanuts, Krazy Kat, Dick Tracy, and especially Tintin. Later, like everyone else, I admired Robert Crumb, Kim Deitch, Bill Griffiths, and other Head comix artists. Edward Gorey was a big influence too. I liked Glenn Baxter and Biff. And then Ben Katchor demonstrated how much further and deeper comics could go—funny, entertaining, thought-provoking and poignant—a real literary art form.

To read the complete interview buy a copy of Observer Quarterly 1: The Acoustic Issue.