Editor's note: Racial, ethnic and gender stereotypes did not materialize from the miasma. They were, and continue to be, made by people, designers and illustrators for whom visual language is reduced to a tweet-like image short-hand. Over the next few months, Design Observer's Steven Heller will revisit the history of certain of these misrepresentations, some of which have stuck like glue to the mental mindset. Others, fortunately, have evaporated. These essays should invite awareness, if not reflection, and if you have examples of how old or new stereotypes are used today, send them to us. We start with a legacy close to Steve's own history.

Today Jewish ethno-stereotypes still exist. For instance, Donald Trump said he prefers Jewish accountants handle his money. That stereotype has long been rooted in the most common of Jewish images: money lender and banker. Yet, in general, unless they are specifi anti-semitic depictions used in Alt-right journals, there are not nearly as many negative, stereotypical caricatures as there once were in publications and on film. It just wouldn’t be politically (or genetically) correct. Pictorial representations of the hook-nosed, shifty-eyed Jew—once common fare in popular cartoons, comics, humor magazines, novelty postcards, sheet music, vaudeville posters, some of them even in Jewish publications like The Yiddish Puck and The Big Stick—would be too absurdly exaggerated for the present.

Jews have been assimilated to such an extent that ultra ethnic features have more or less vanished. Ok, Crusty the Clown of the Simpsons is based on a Borsch Belt comic, but he doesn’t look like Shylock. Jerry Seinfeld doesn’t even look Borsch Belt. There are still Jewish humorists, like Mel Brooks and Woody Allen, but unless they're making satiric commentary, the stereotypes are gone.

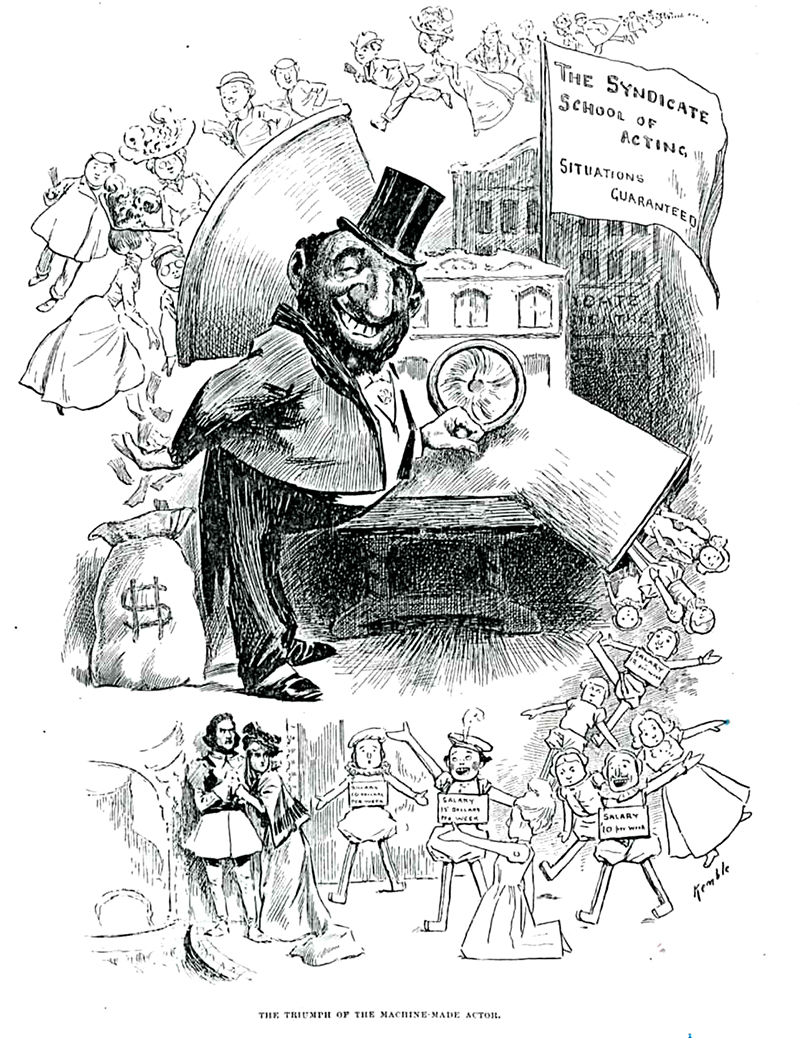

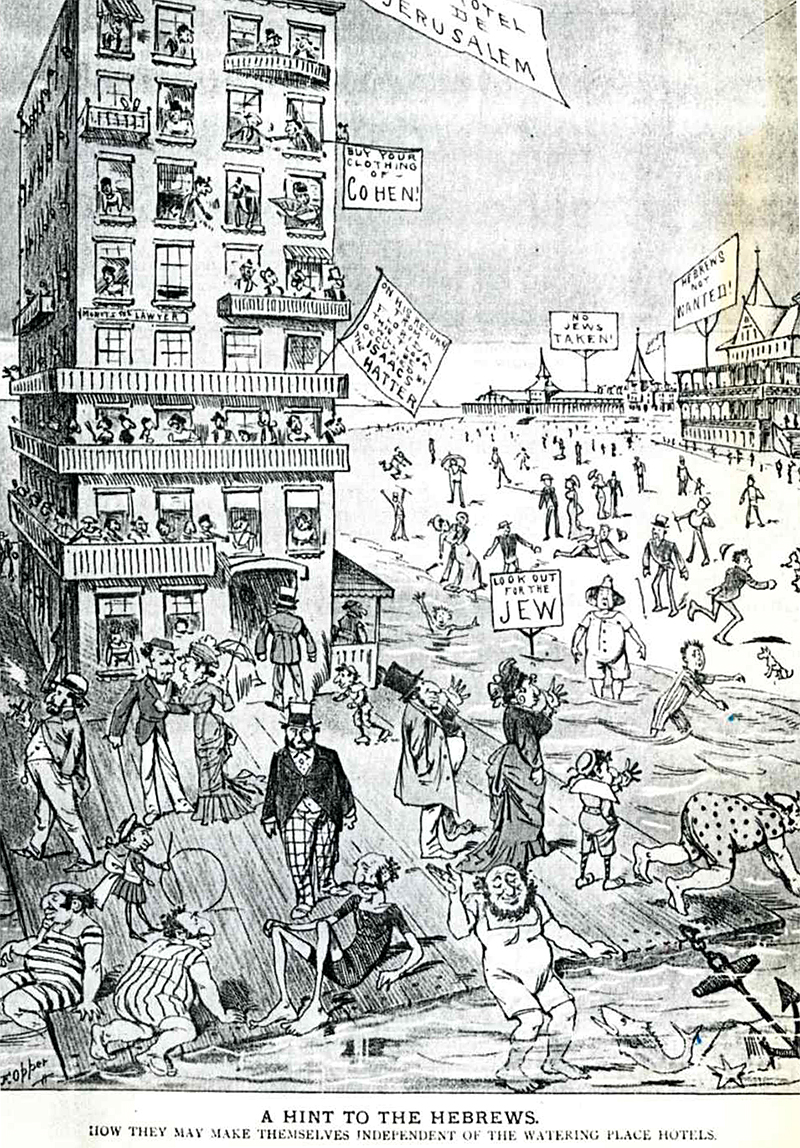

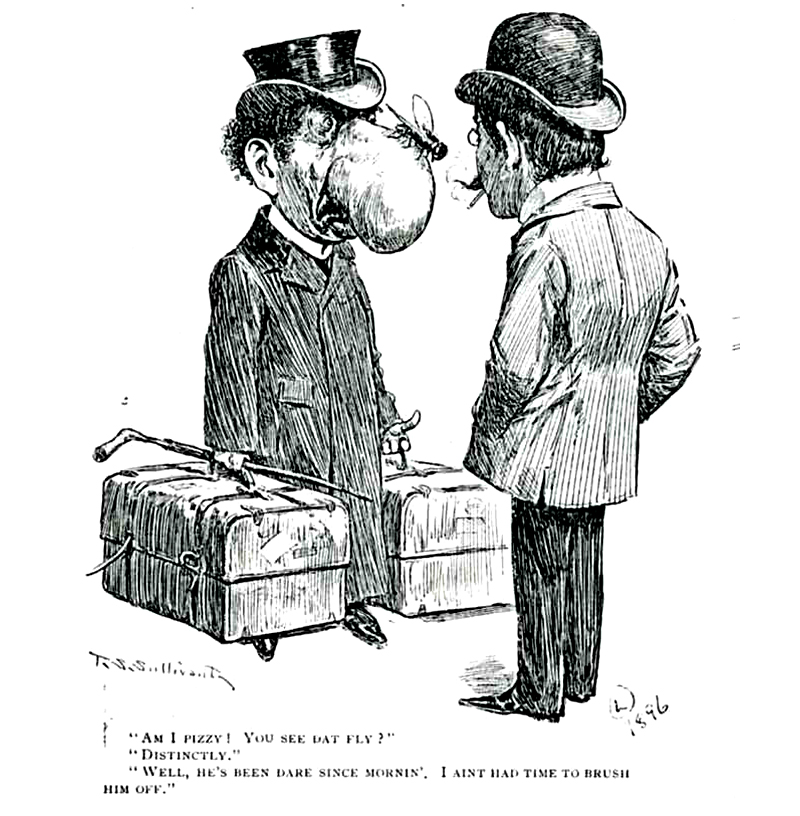

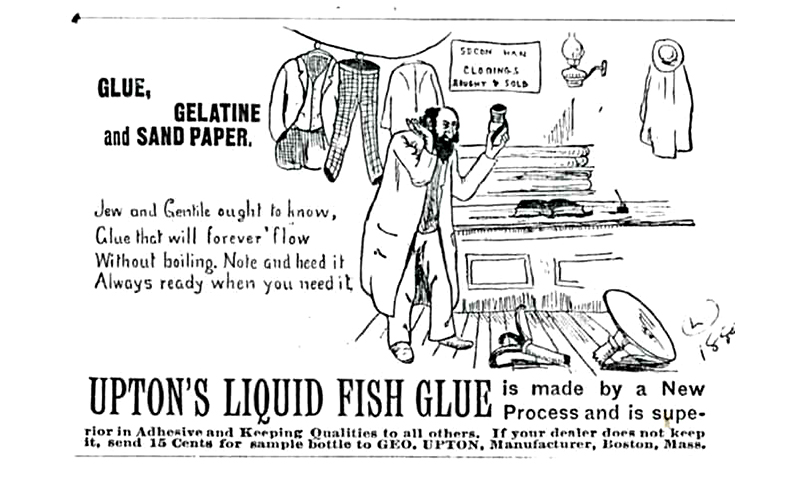

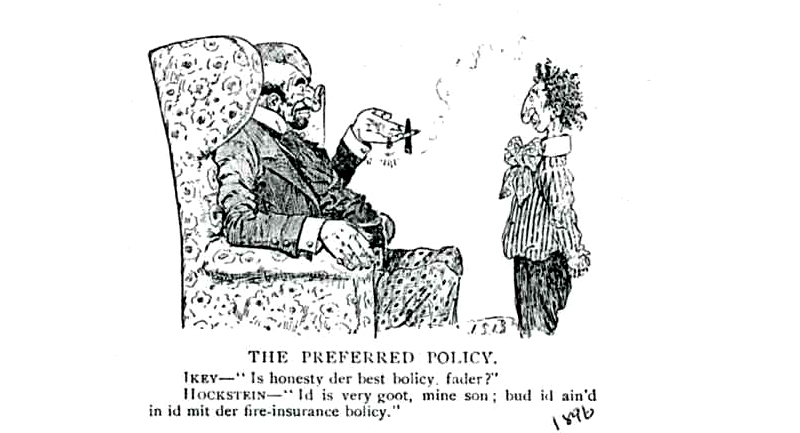

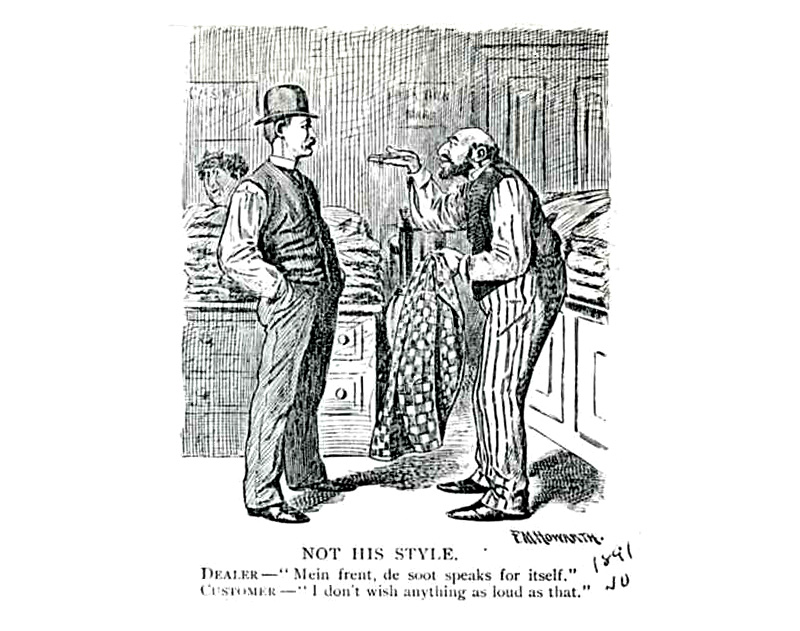

Nonetheless, the visual stereotypes were very popular in the early twentieth century for social and political reasons. Stereotypes emphasize difference, which can be insulting and descriminating. Stereotyping demonizes the victims of the image, reducing them to a status of “otherness.” Many immigrants and ethnic groups experienced comic and malicious stereotyping in the United States and abroad. Eduard Fuchs, a graphic image historian, wrote Die Juden in der Karikatur in 1921, one of many books on how Jews were depicted in both representational and exaggerated form. He showed through 12th century woodcuts Jews in typical dress, engaged in uncomfortable rituals, and unflattering situations. 19th century racist historians, including Sandor Gilman and Houston Stewart Chamberlain, used these images to show the mongrel qualities of the Jews who sought social and political equality in Central and Eastern Europe. The images were adapted by American artists into visual icons of a swarthy, hooked nosed, and otherwise inferior race that should be excluded from the mainstream.

Another defining characteristic was as the merchants of greed, huckstters, purveyors of shoddy merchandise. The pawnbroker was a common image of anti-Semitism; a parasitic member of society that preyed on the unfortunate. And one of the most frequent recurring portrayals was the result of intermarriage between Jew and Christian, an interbreeding that resulted in unpleasant looking defiled children. These images served the purpose that the “races” be separate from the dominant White Anglo Saxon class.

Things have changed radically since the early twentieth century when these images were predominantly accepted. Today, they are more subtle, more nuanced and hidden from view. Still, it is worth remembering that negative visualizations are powerful tools of descrimination. Vintage Jewish stereotypes maybe gone but they are not entirely forgotten either.