There are are 33 ethnographic busts on the rear façade of the Jefferson Building of Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. It was described in the Library’s 1897 Handbook as the “first instance of a comprehensive attempt to make ethnological science contribute to the architectural decoration of an important building." Designed by William Boyd and Henry Jackson Ellicott, they include examples of distinctive races and ethnicities of Russian Slavs, Hindus, Jews, Abyssinians, Polynesians, Japanese, Tibetan, Chinese, and more and generalize the representative physical characteristics of the world’s peoples. They also harken to a trait of this country to categorize and distinguish difference. The motivation for these busts was to foster understanding, not to perpetuate prejudice, but they vividly illustrate racial differences which have been used to promote degrees of racial and ethnic stereotyping from harmless to harmful.

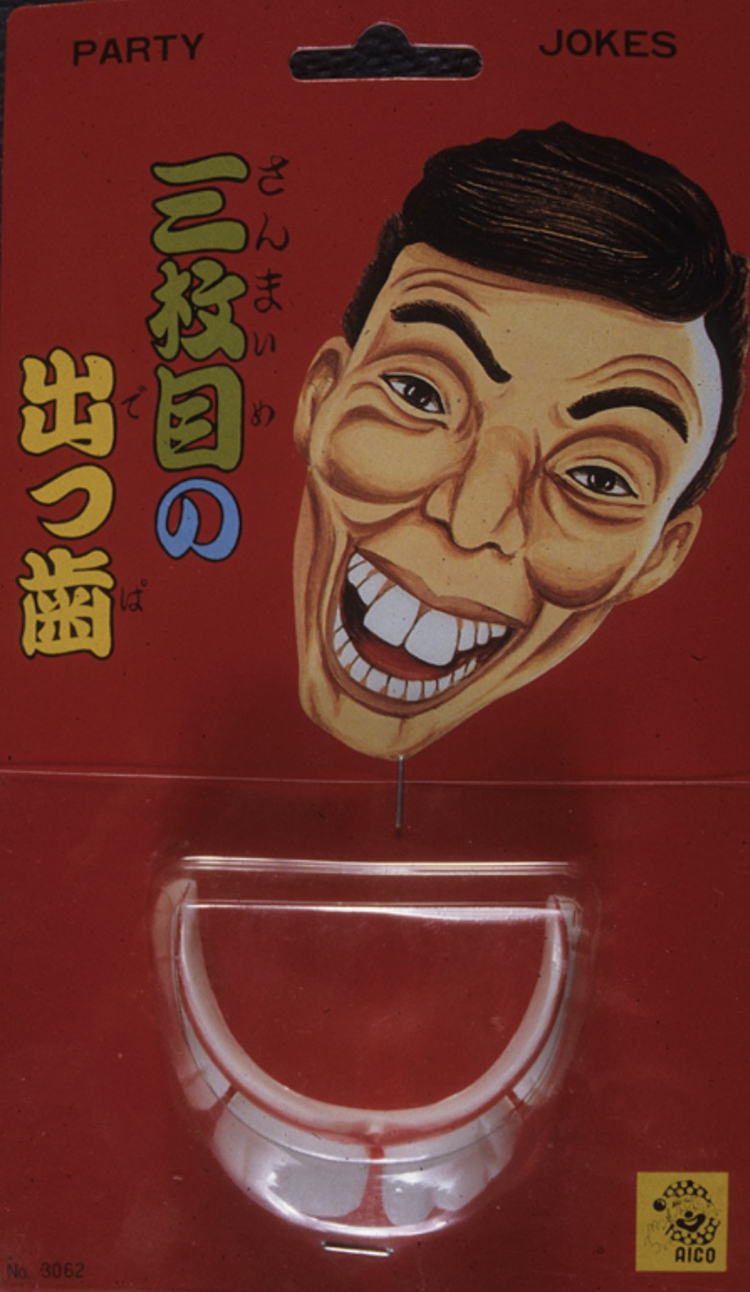

“Victims of the Image” looks at how difference has been exploited in visual media, at times to entertain, to ridicule, and to exclude. Some historians argue that racial caricature is a right of passage or even a self-selecting parodic way to introduce non-Americans into the American patchwork. Others counter that stereotyping diminishes individuality by creating pictorial ghettos. How people in the U.S. from differing cultures ultimately melt in the proverbial melting pot—or not—is made vividly clear through the history of mainstream stereotypes, caricatures, and cliches. The over-generalization, what might also be called a kind of visual hazing in popular art and design of Asians was long maintained for different purposes.

When Asians were the targets of cartoonists during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the particular focus was on the Chinese, in large part owing to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. The act was created by Congress and signed by President Chester A. Arthur to forbid Chinese laborers from immigrating for ten years. The first such federal prohibition, its enforcement arm, the Geary Act, was on the books until 1902 and and helped spark the widespread anti-Chinese immigration movement at the time.

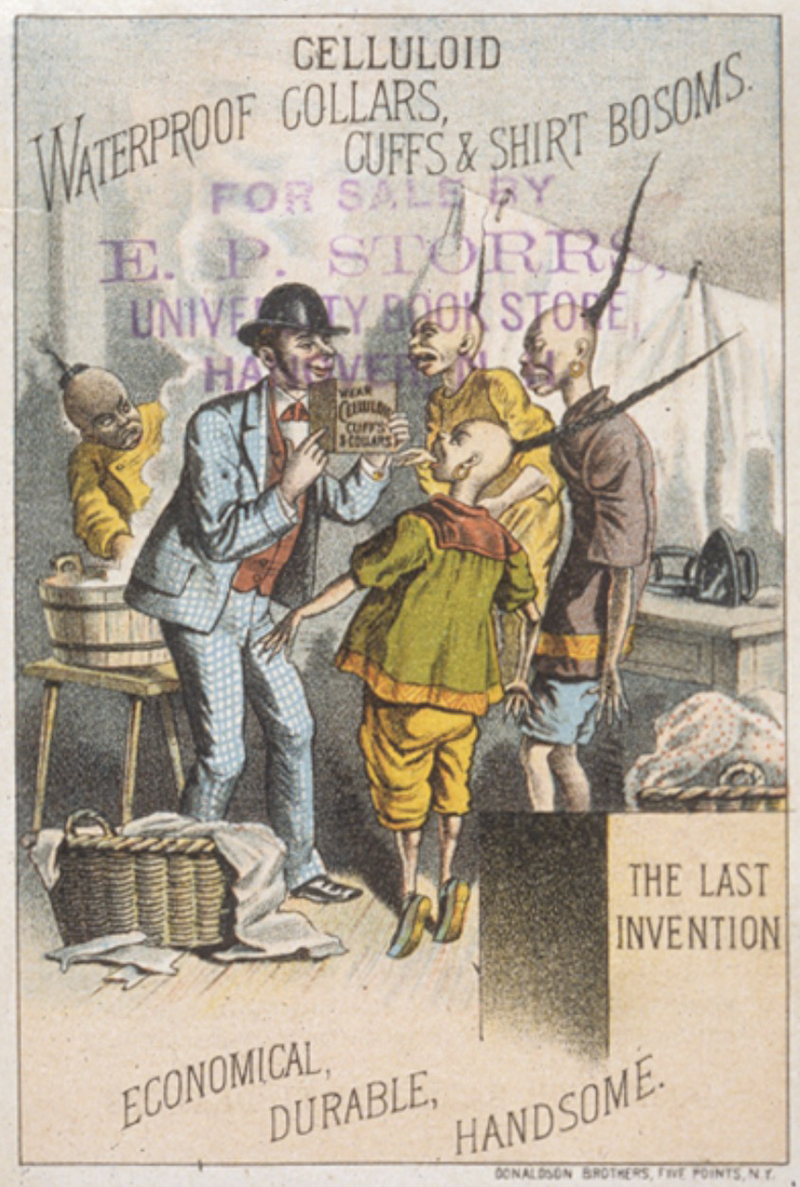

An outgrowth of this official policy was evidenced by the cartoons, advertisements, trade cards, and other popular art that supported the deracination of these and other Asian peoples. The cliches used to smear Chinese—or what overall was called the "Yellow Peril"—were savage, dehumanizing portrayals in media, such as rat-tailed demons.

In 2014 I wrote for The Atlantic about an insightful anthology of writing on racial and racist stereotyping, Yellow Peril! An Archive of Anti-Asian Fears, edited by John Kuo, Wei Tchen, and Dylan Yeats (Verso). In the book, the authors describe how demonizing Asian peoples in word and picture was acceptable in America for so long.

According to Tchen, the term “Yellow Peril” was used as a modern political pejorative by Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm, responding to his cousin Russian Czar Nicolas’s defeat in his war against Japan in 1905. Tchen noted that Wilhelm commissioned an artist to draw a “threatening Buddha in a lotus position riding a dragon thundercloud off in the distance.” This was not an effective piece of propaganda by contemporary standards Tchen says, “but it did get at some basic dynamics: the threatening, evil man marked by certain exaggerated and racialized physical characteristics. It gets the juices going for men to become protectors.”

Stereotype works best through distortions of truth. Since Asians have distinctive features—eyes, hair, cheekbones, etc., and dress, they were easy targets for artists. Chinese were visually portrayed as subhuman, dirty and opium pushers. In early graphic depictions their unusual native dress and hair made them seem clownlike. In later Hollywood characterizations they were either servile house help, vamps, prostitutes, or laundry men.

I asked Tchen, was there one person or event responsible for creating the typical image? “From my research, the transplantation of Anglo-Saxon Protestantism into a potent Anglo-American Protestantism is key,” he said. “This was the underlying, interlocking political culture which formulated a particular notion of the property-owning, white, male, superior, rational male benevolently (and by right) presiding over an expanding north America—with Canada in their sights, south into Mexico and the inferior Spanish colonies, and westward into the Pacific with the luxuries of ‘the Orient’ always beckoning.” When part of the manifest destiny ideal was threatened, “the fallback position was to promote what historian Alexander Saxton called a ‘white republic’ with a racially exclusive form of wage labor and industrialization excluding those deemed too ‘lazy’ or too ‘hard working.’”

Negative images are linked to desire for and admiration of their targets. In the history of the U.S., it doesn't take much for dangerous “minorities” to become “model minorities.” Tchen said, “It’s all a question of whether they get incorporated into the society or not. As Asians go, Fu Manchu and Ming the Merciless: No. Charlie Chan and the ‘hard-working’ ‘foreign’ service worker who know their place: Yes.”

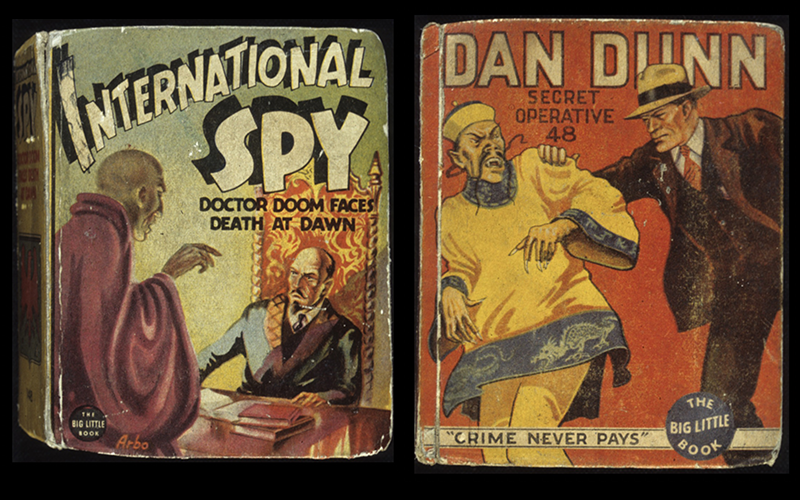

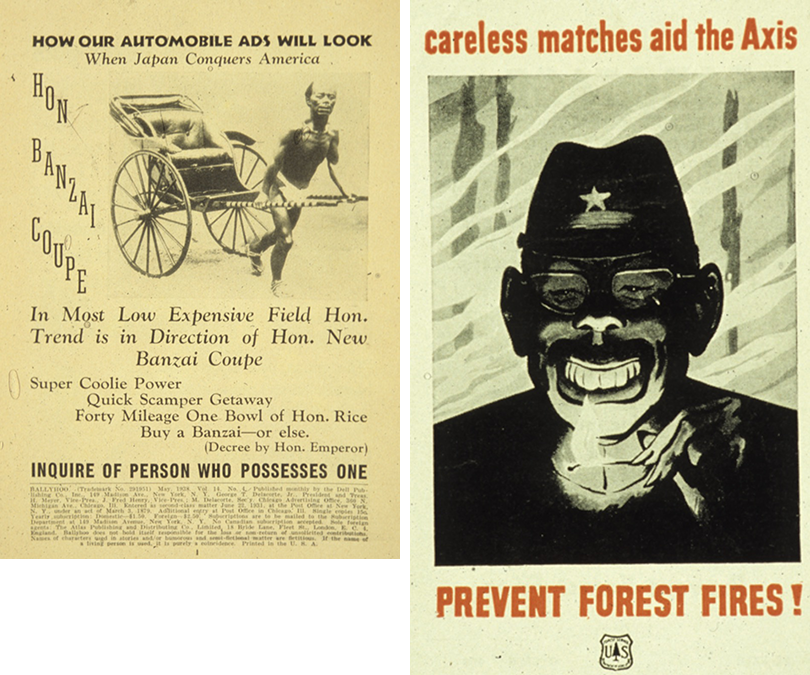

World War II unleashed a torrent of monstrous anti-Japanese vitriol. Anti-Asian notions were not only injected into politics, they were present in American entertainment, and were the reason for the success of certain books, magazines, and films. Cheap pulp magazines offered exploitative images that sold well.

There was no dearth of images showing barbaric hordes of heathen Chinaman wanting to rape white women, which filled the English-language print culture. “These are the conditions within which Henry Sarsfield Ward was inspired to write the first Fu Manchu stories and to further enchant the East London docks of Limehouse as his fictional base of power,” Tchen says. “Ward became Sax Rohmer and soon the great Boris Karloff became the evil doctor.” Those of a certain age will remember Flash Gordon of Earth fought Emperor Ming of Mongo, an Asian stereotype from outer space.

Tchen also looked at whether these images were messages of hate or came out of any other emotional rationales. “Ignorance plus distrust plus saber rattling are a deadly combination,” he noted. “Oriental exotic difference, as practiced in the political culture and commercial media, necessarily tap a range of gut feelings and reflexes. ...‘They eat rats don’t they?’ Or worse. ‘Don't they eat dogs?’ These are the Ick! and Yuk! factors that go with Yikes! It’s not all hate, but the line in the sand is drawn between we civilized, normal, hence superior people versus ‘them.’”