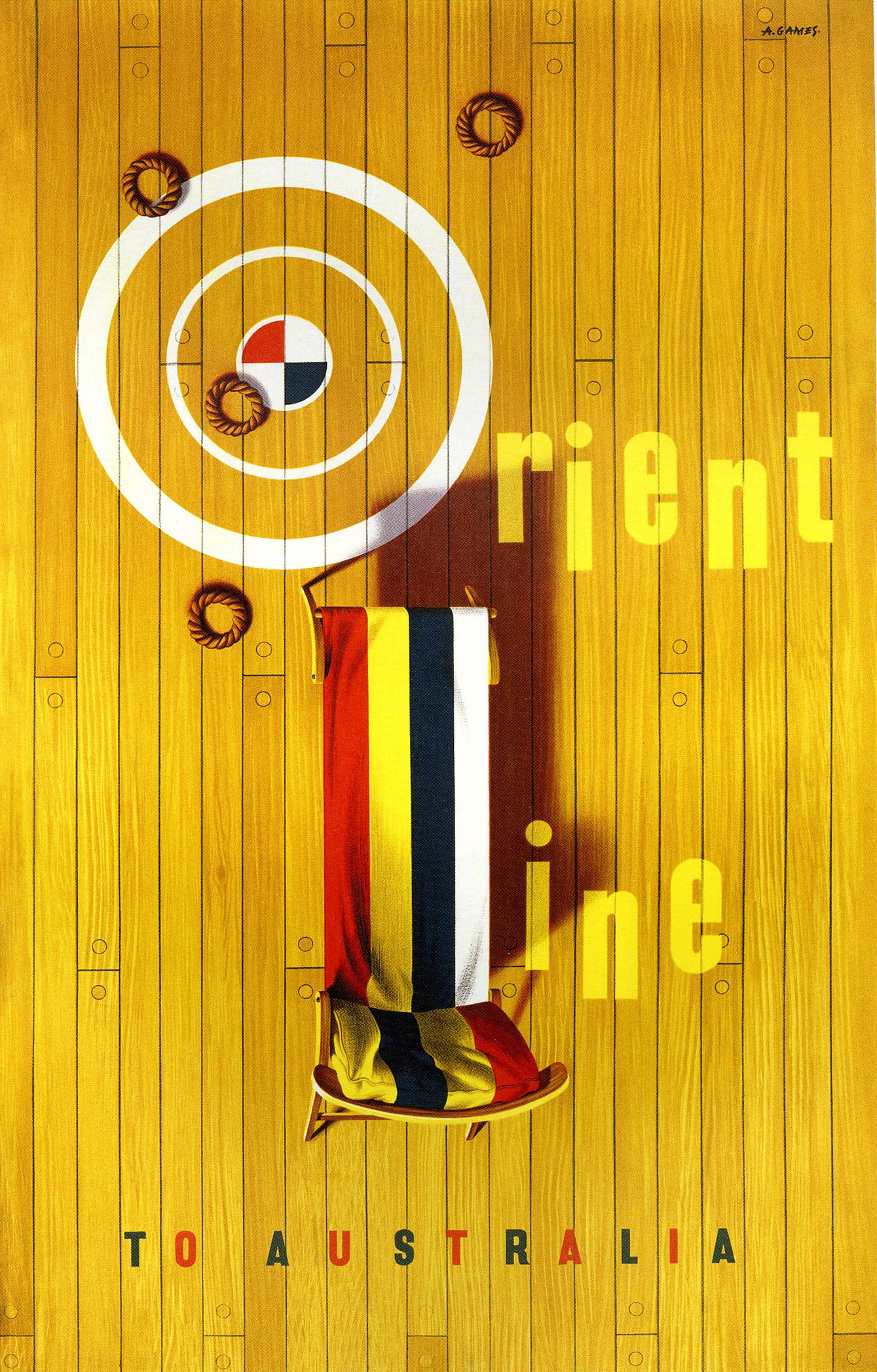

Designer: Abram Games. All images from The History of Graphic Design Vol. 1 1890-1959.

Ooouch! I just lifted onto my lap the heaviest—also, I suspect, the largest—graphic design history book ever produced. I don’t know how many pounds (or stone) it weighs, but carrying it from bookstore to home demands Olympic-grade weight-lifting prowess. It also stands taller than virtually any book in my library, and so there is no shelf on which I can even store it.

The book is The History of Graphic Design Vol. 1 1890-1959 (Taschen) by Jens Muller, edited by Julius Weidmann. (Full disclosure: I provided a supportive blurb for the book when I saw it in the much lighter-weight PDF format). It is an impressive work produced by a respected design historian (whose recent Pioneers of German Graphic Design I favorably mentioned here). But it is nonetheless such an unwieldy volume, similar to those plump scholarly Oxford or Webster dictionaries that are so huge that to turn their pages you must sit them on a podium. In fact, this is not one, but Taschen has published books that come with their own podiums. Yet, that is not the gist of this essay. What concerns me of late is the frenzy—a cross between the Gold Rush and Easter egg hunt—for images to fill a rash of design histories, chronicles, and documentaries devoted to our field’s discovery and preservation.

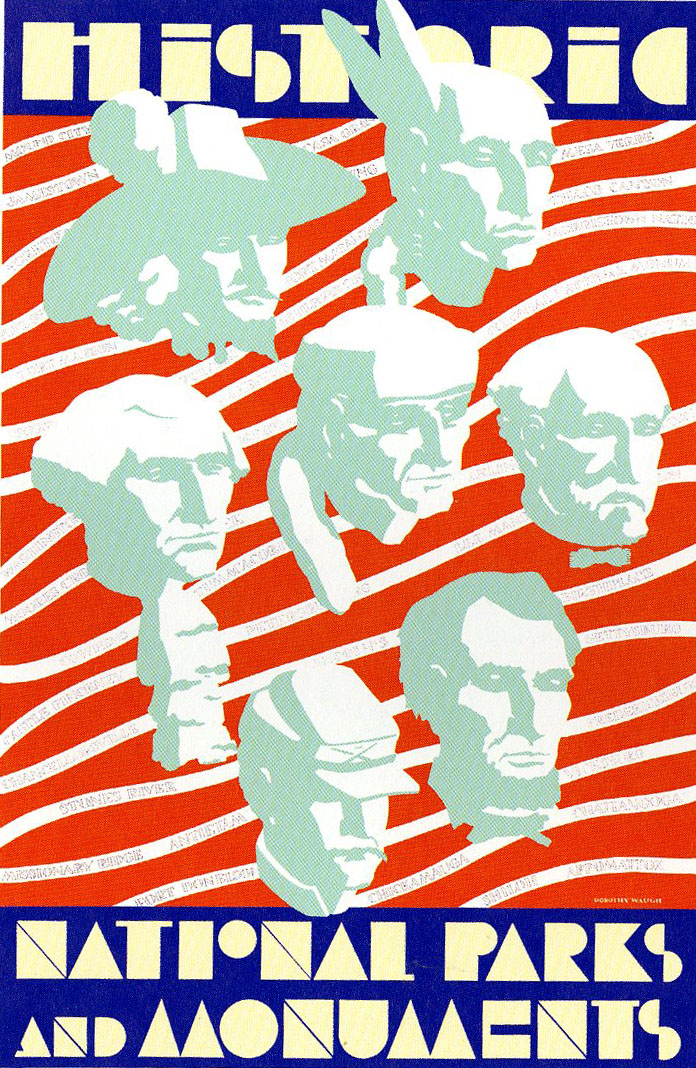

Designer: Dorothy Waugh. All images from The History of Graphic Design Vol. 1 1890-1959.

Since Philip B. Meggs published the first edition of A History of Graphic Design in 1983, which he purposefully called “A History” not “The History,” knowing that more books would follow, I have, among other practitioners, scholars, and collectors of graphic design and illustration (i.e., commercial art) histories torn through masses of primary and secondary printed matter, scouring bookstores, flea markets, auction houses, archives, storage bins—indeed whatever and wherever artifacts have been squirreled, filed, and, yes, forgotten—in search of unknown or barely considered materials that in some way fill in the blanks or create new categories and genres of graphic design history. What has resulted is a mixed blessing. There is a lot that is worthy and unworthy for consideration.

Unknown work by lost or anonymous makers have indeed been uncovered, documented and introduced, thus expanding an admittedly limited male, Eurocentric, white, exclusively educated canon. Some deserved the elevated status, while others were simply curiosities. But enlightenment never hurt anyone. Designers are not the only benefactors of this new material, either. Graphic design is intertwined with so many commercial, social, political, ethnographic, and technological areas that each discovery opens doors in major and minor areas of interest. That’s all good.

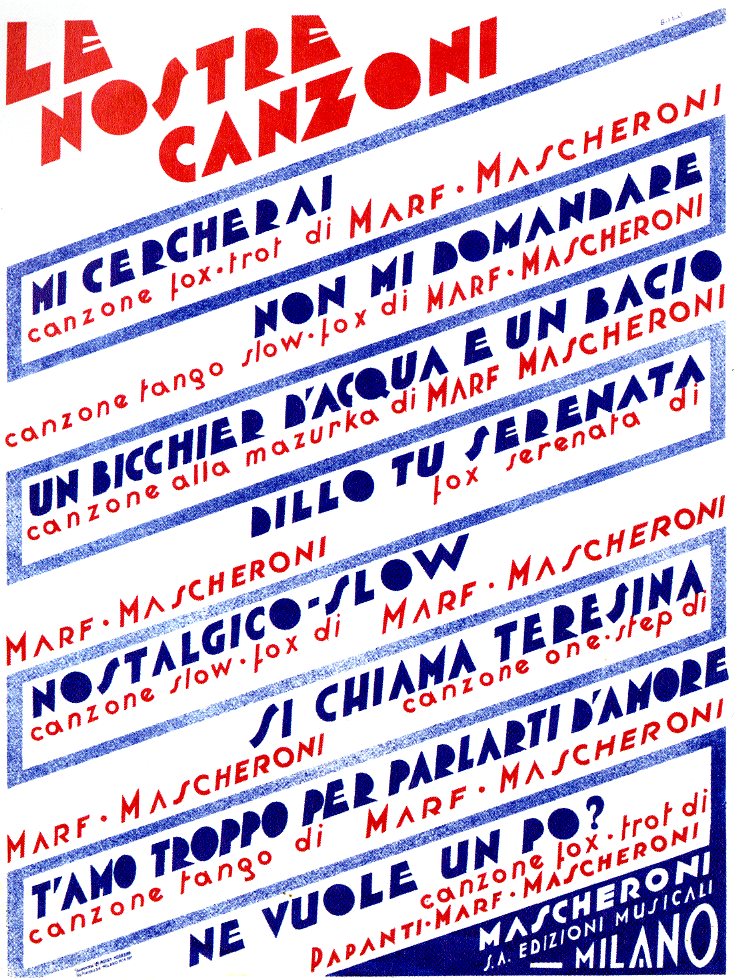

Designer: Gilbas. All images from The History of Graphic Design Vol. 1 1890-1959.

There is a tremendous increase in redundancy in books and exhibits. The same canonical imagery—the ones that bring museums and archives considerable profit in reproduction fees—are invariably going to be used again and again, and with good reason. Back when design history was in its infancy, these (mostly posters, which have long been highly collectable) were earmarked as iconic. How is it possible to discuss Russian Constructivism without “Beat the Whites With The Red Wedge” or American corporate identity without Paul Rand’s “IBM” eye-bee-m rebus. It is possible to leave them out, but some critic will invariably and reasonably ask why. It is possible to reproduce lesser or unknown works by these two designers and few will not say, “That’s a rare find, congratulations!” But publishing mostly unknown material begs the question: “Is this work up to the standard of the canon?”

I’ve faced this issue with some of my books where editors argued I have to show such-and-such or so-and-so simply because it would be either misleading or mistaken not to, when I would much prefer to add more new or lost material to the mix. It is invariably more exciting for a writer or researcher to convey the story of this material than rehash well-told tales. But this causes a quandary of sorts. In Jens Muller’s sweeping survey of over 60 years, his mandate is to show the familiar icons…if only for accuracy. Also, publishers are forced to assume that that audiences for such books are new to the field, so this may be the first sighting for many of them. Still, one of the jobs of today’s design historians and documentarians is, rather than to pick the low-hanging fruit, to reach beyond and find well-known designers’ lesser or unknown work, analyze it to determine its value to the individual’s legacy and history in general, and seek those obscure items that may stimulate inspiration and further discovery—even if it’s, well, not as good.

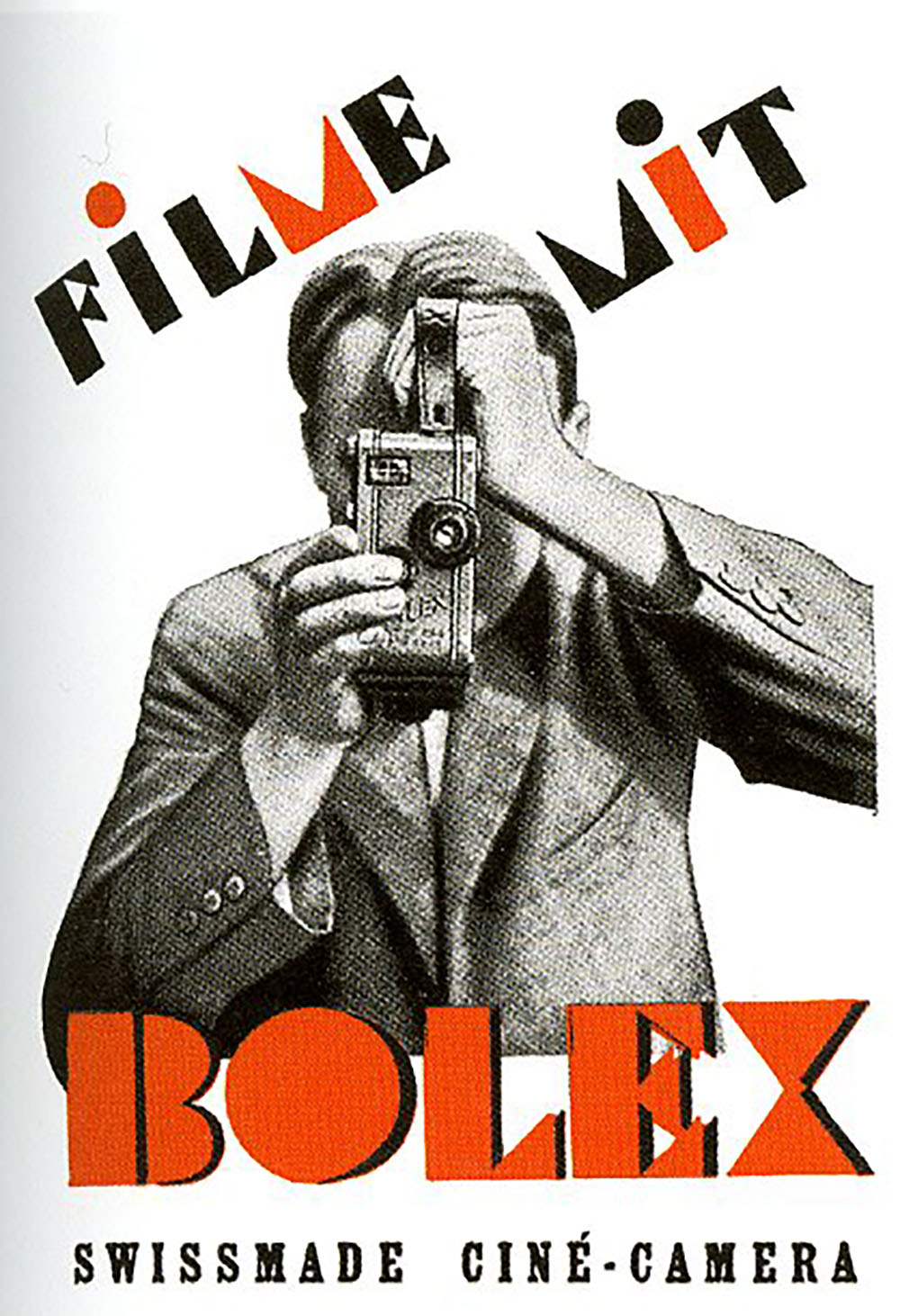

Designer: Walter Cyliax. All images from The History of Graphic Design Vol. 1 1890-1959.

Admittedly, many of my own books, articles and exhibitions rely on famous objects, but I always struggle for “diversity”—for those pieces that, when I find them, send me into a state of euphoria like what Amerigo Vespucci probably experienced around 1502 when he discovered that Brazil and the West Indies did not represent Asia's eastern outskirts (or some other apt analogy). There are certain risks involved. For our recent book The Moderns: Midcentury American Graphic Design (Abrams) co-authored with Greg D’Onofrio, we made a conscious effort to include designers who had not been as widely covered under the “modern” umbrella, including women, persons of color, and those who were not entirely orthodox in the modern methods. We, too, clawed through stacks, drawers, and boxes of things that have not been republished in current design histories. The challenge was to balance the known while capturing the unknown. Never-having-been-seen-before was not a good enough criterion on its own; finding new artifacts on which graphic design history can evolve from its accepted standard was (and should be) the goal. Whether heavy or light, fat or thin, a book with too much redundant imagery does not keep our historical legacy vital. Let’s capture the lost, ignored, and wild.

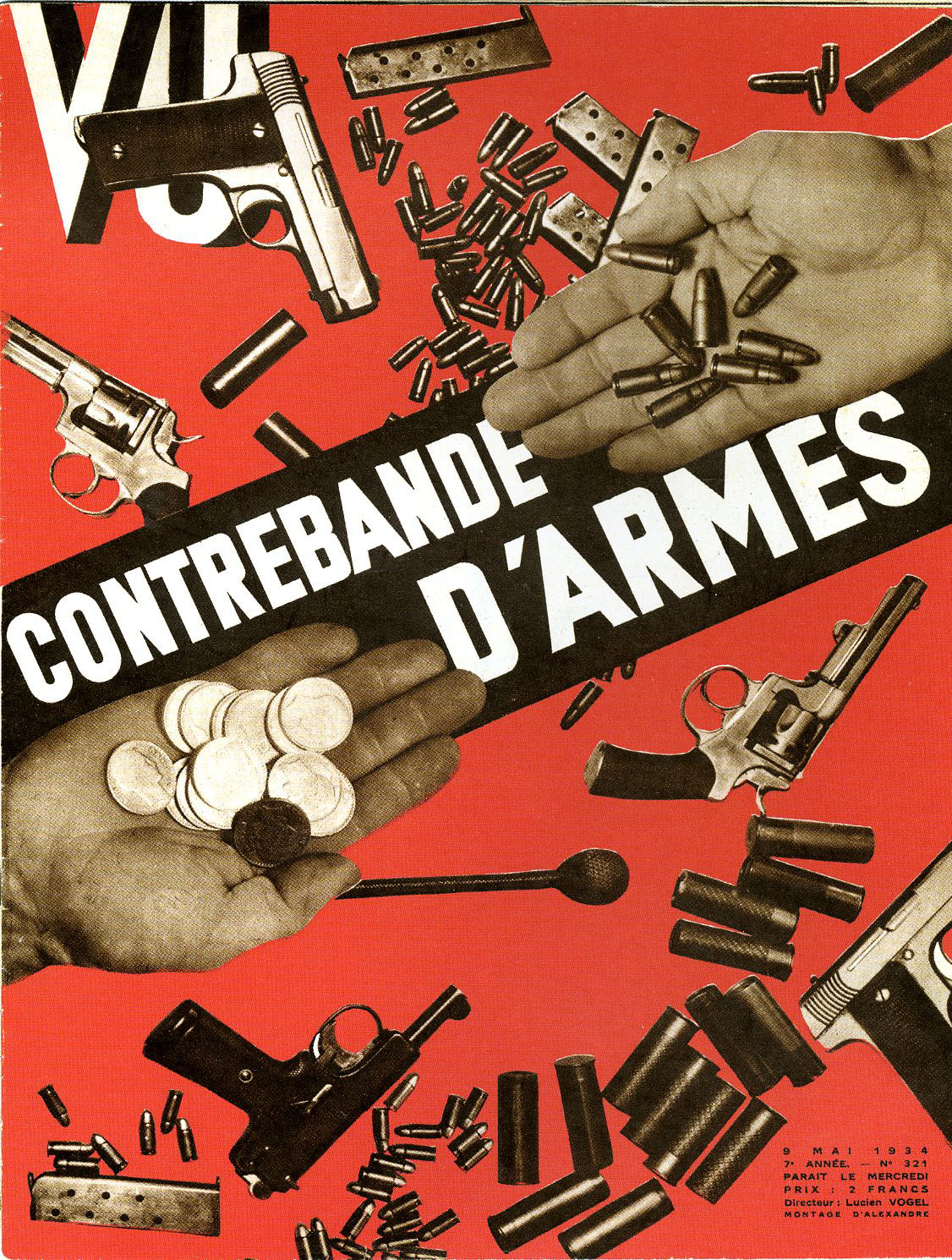

Designer: Anonymous, VU magazine. All images from The History of Graphic Design Vol. 1 1890-1959.