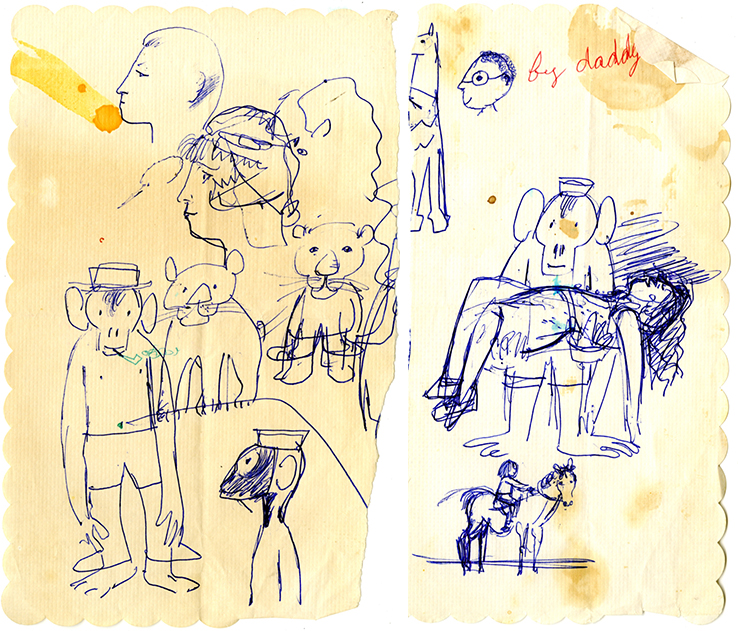

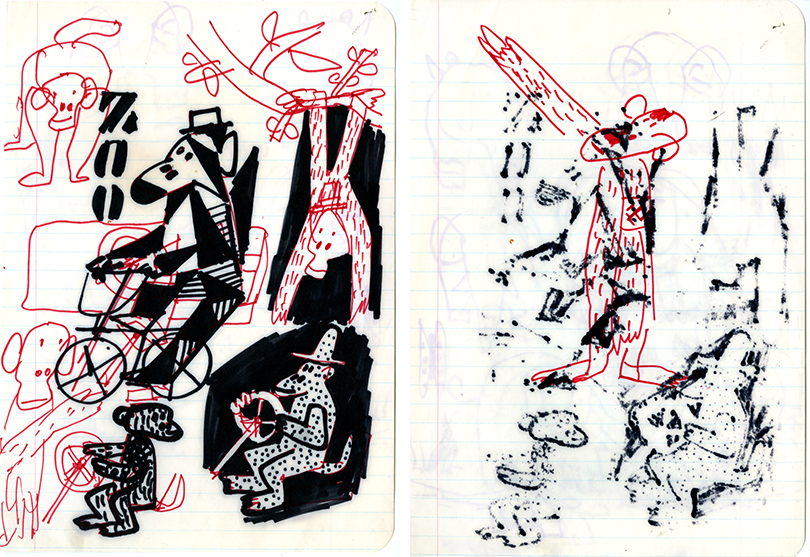

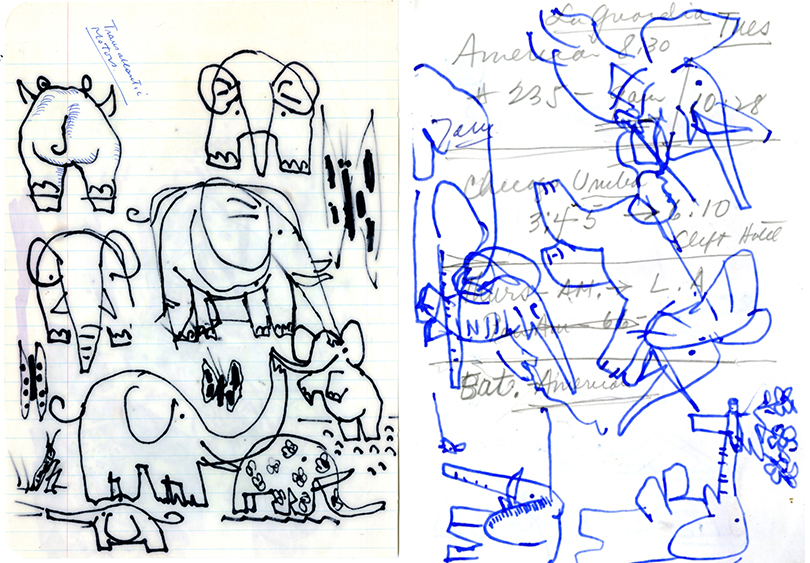

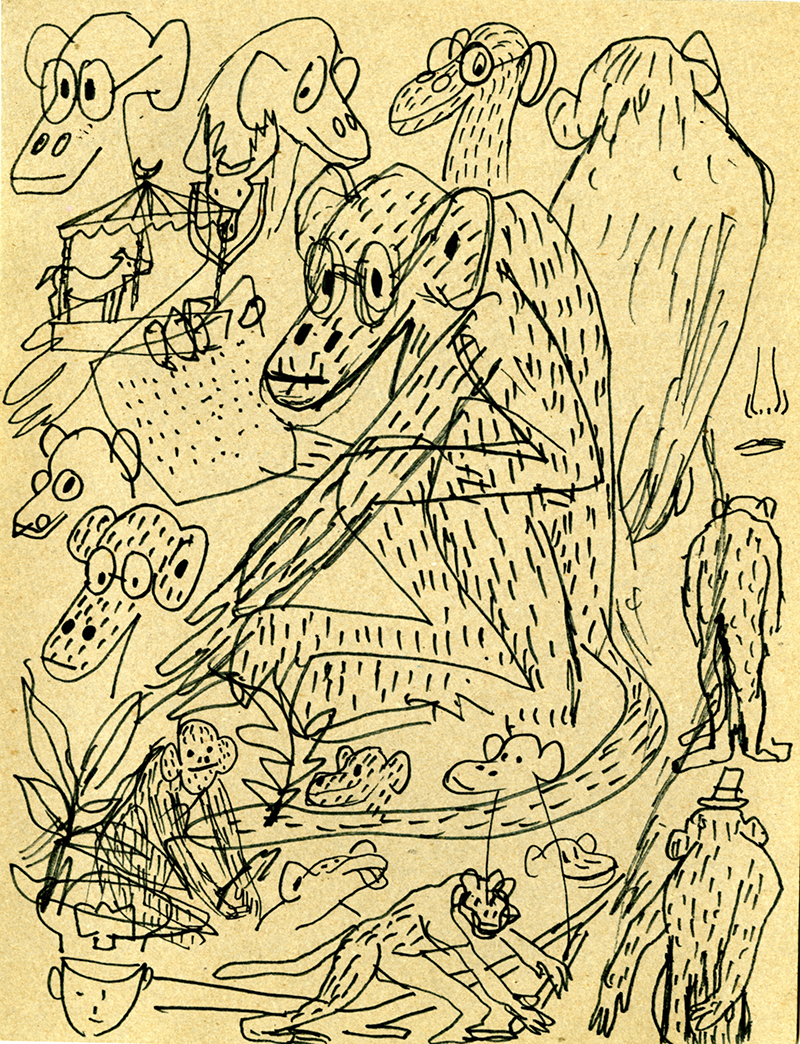

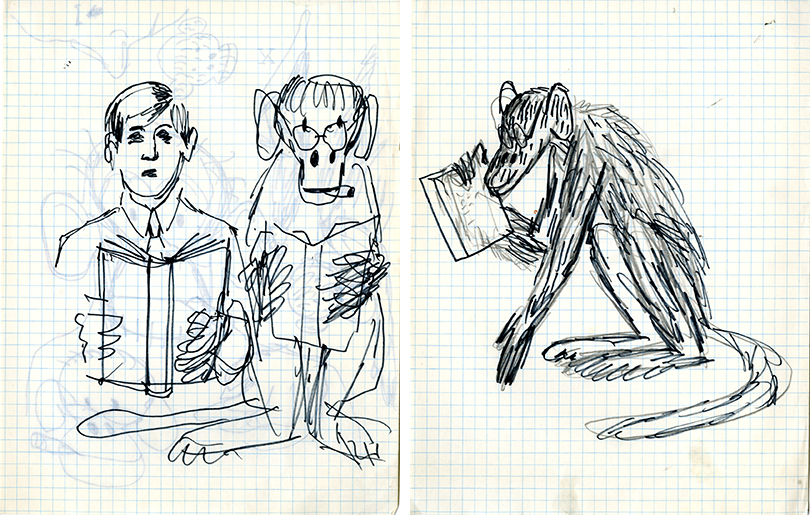

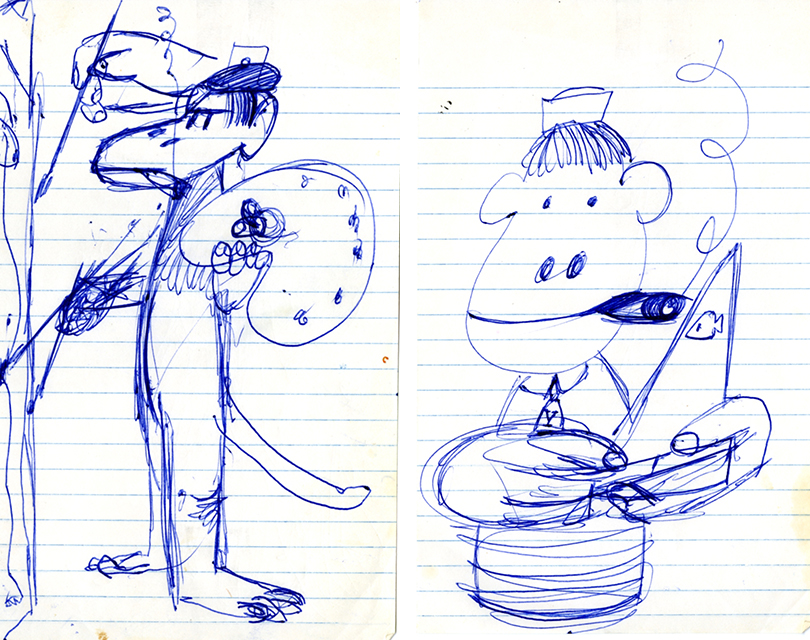

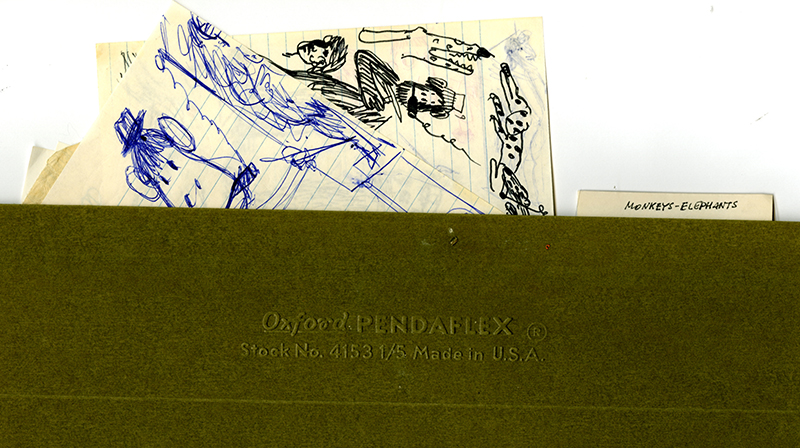

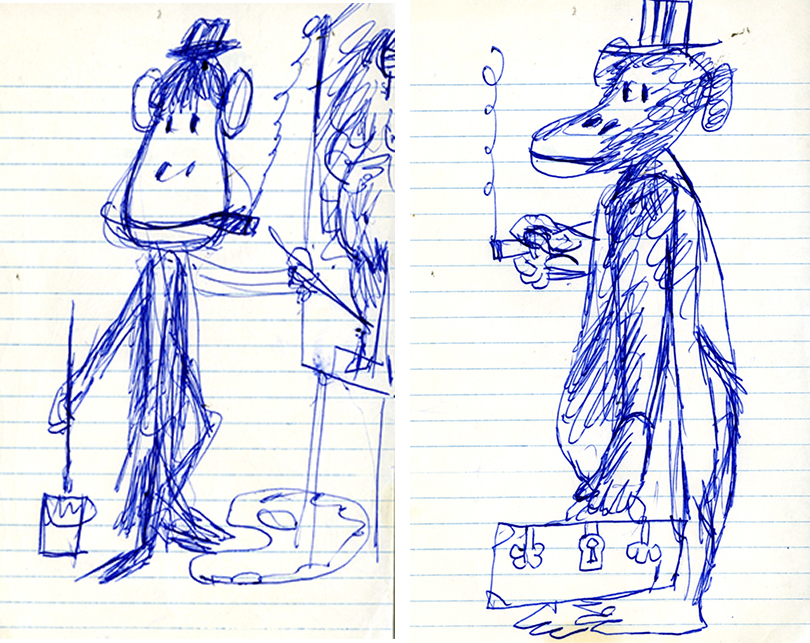

If anyone knows why Paul Rand kept a file folder of sketches in his desk with the title “Monkeys and Elephants” I’d like to know too. It was not a fat folder; maybe a couple of dozen comical doodles drawn on random scraps of paper, cardboard, and napkins. While he used elephants (as well as tigers, rabbits and horses) to my knowledge, he never used monkeys in his work.

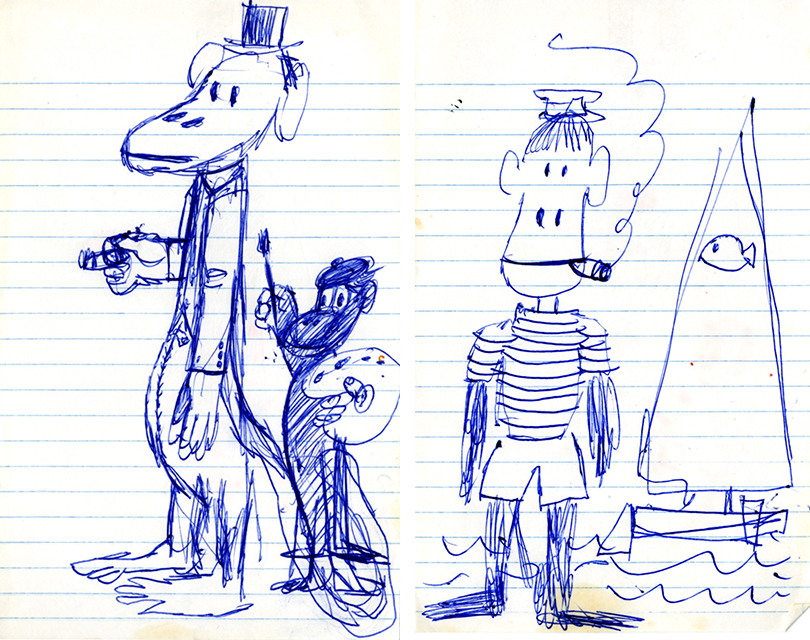

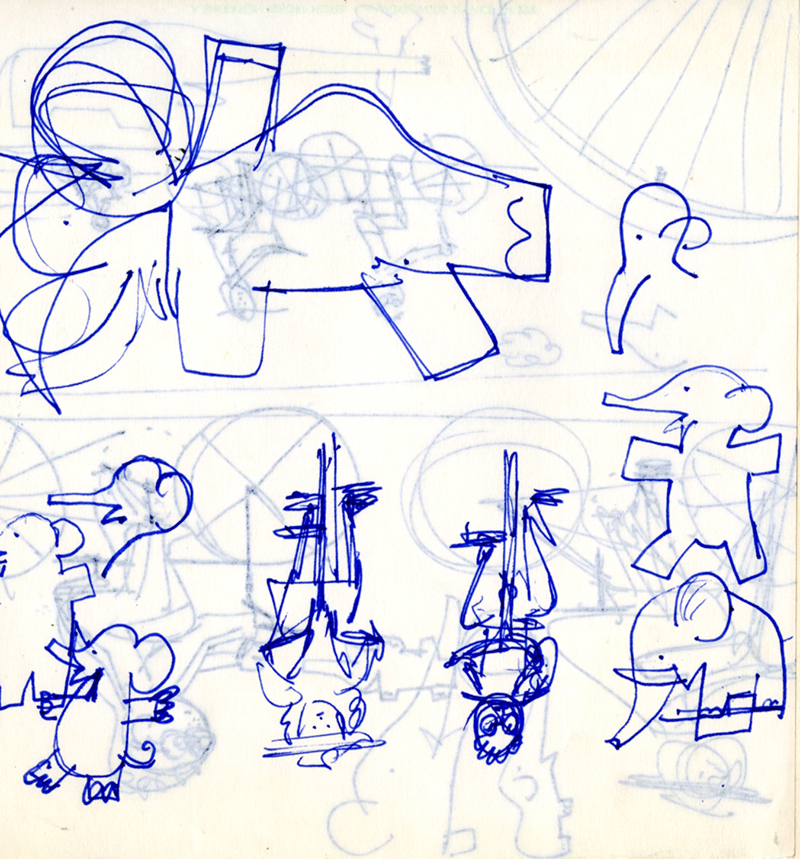

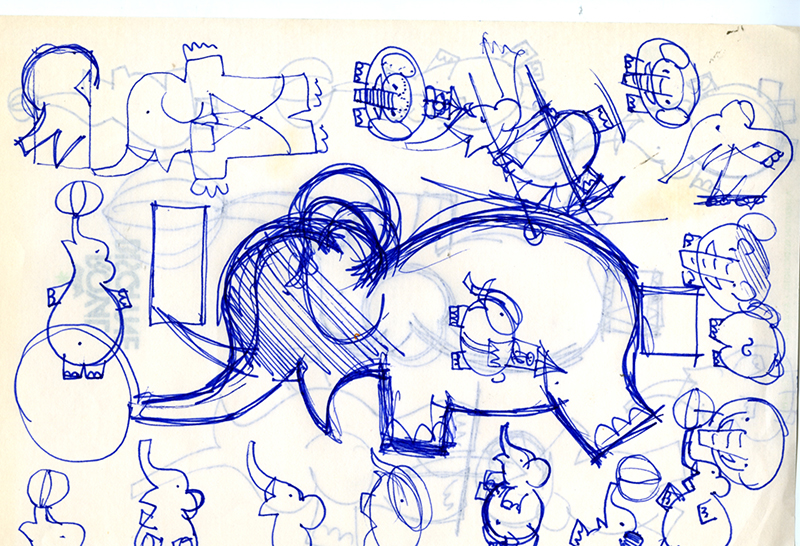

I can understand why he liked elephants. There is something indescribably modern about the pachyderm’s curious other worldly form. In 1945 using their revolutionary molded plywood technique — the basis for such modern furniture as the Eames Chair — Charles and Ray Eames developed a toy for sitting called the “Eames Elephant.” But Rand’s monkey business was and is an unsolved mystery — and goodness knows I’ve researched far and wide.

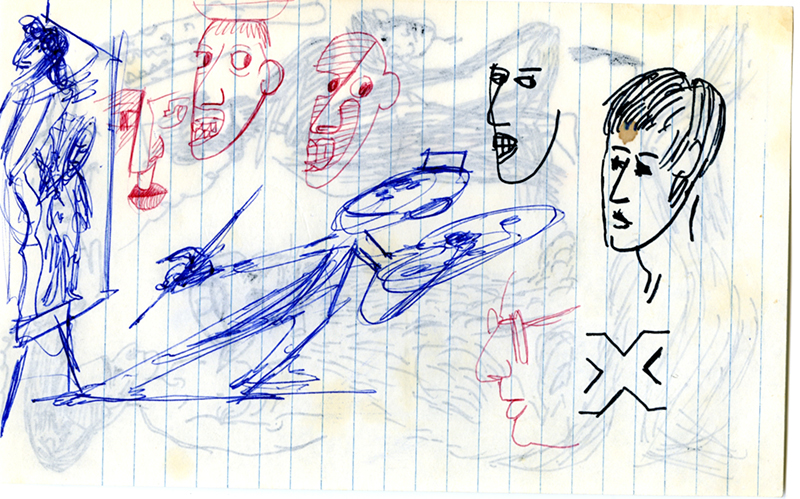

Rand was always drawing something. It was the core of his play principle. “I don’t think play is done unwittingly,” he told me. “At any rate, one doesn’t dwell over whether its play or something more serious — one just does it.” So, it is safe to assume that his monkeying around was a conscious-unconscious act of creativity. If there was not a semblance of self-consciousness, he would not have kept a file. However, these drawings were not, as many often were, the basis for one of his logos, posters, or book covers.

The elephant was significant insofar that it was designed by nature in a most unnatural unusual way. Being that the monkey was man’s closest ancestor, maybe this primate reminded him of some of certain clients. I can see Rand in my mind’s eye, wittingly drawing a chimp while talking to one of these clients on the telephone. Of course, this is simply a theory, but so is evolution.