The February 17th edition of the Sunday Review, which Ralph Nadar declares illegible.

Ralph Nader’s 1965 book Unsafe At Any Speed: The Designed In Dangers of the American Automobile convinced my father to install seatbelts in our 1960 Oldsmobile, which saved his life when, on a business trip, he swerved off the highway at night and landed upside down. No seat belts, no dad. So, as the pioneer consumer advocate I’ve always had a fondness for Nader, even when he ran for President in 2000 tallying up over two million votes making him the spoiler that arguably helped George W. Bush and Dick Chaney get into office. I did not like the outcome, but Nader deserved respect. Recently, he’s entered murkier territory.

On February 27 he posted a story on Nader.org titled “Unleashed Graphic Designers: Art Over Function” where he regurgitates many of the usual complaints about legibility since Guttenberg (“Hey Johannes, can you make the type larger and we’ll have 32 instead of 42 lines so the older monks can read it more effortlessly?”) This new article is laced with generalities and untruths about contemporary newspaper design.

“In today’s print news, legible print is on a collision course with flights of fancy by graphic artists,” his blistering attack begins.

“Admittedly, this is the golden age for graphic artists to show their creativity. Editors have convinced themselves that with readers’ shorter attention spans and the younger generation’s aversion to spending time with print publications,” he argues cogently, “the graphic artists must be unleashed ... Space, color, and type size are the domain of liberated gung-ho artists.”

Yes. that’s exactly what designers do—they balance space, color, and type size—as opposed, to say, operate the Hadron Collider.

“There is one additional problem with low expectations for print newsreaders,” Nader hammers home. “Even though print readership is shrinking, there will be even fewer readers of print if they physically cannot read the printed word,” he adds without considering the reality that young people live on their phones (maybe that should be the target of his ire—unsafe at 5G.) But Nader’s not ignorant. He has to know that reading habits change from generation to generation as do printing technologies. I guess he forgot.

“I have tried, to no avail, to speak with graphic design editors of some leading newspapers about three pronounced trends that are obscuring content,” he notes. “First is the use of background colors that seriously blur the visibility of the text on the page. Second is print size, which is often so small and light that even readers with good eyesight would need the assistance of a magnifying glass. Third is that graphic designers have been given far too much space to replace content already squeezed by space limitations.” All are reasonable concerns if news art departments were indeed guilty of doing this. Although some papers may be poorly designed, this is not the state-of-the-field, the intent of most designers, or the reason that the industry is now faltering.

“Function should not follow art,” which is true, but show me where these problems occur in any major newspaper section and I’ll vote for Mr. Nader the next time he runs for office. “Readers should not have to squint to make out the text on the page. Some readers might even abandon an article because of its illegible text! One wonders why editors have ceded control of the readability of their publications to graphic designers,” he adds, referring to no particular designers, art directors, or editors that I’ve ever met. Editors are very turf conscious. While Mr. Nader correctly states that “Editors cannot escape responsibility by saying that the graphic designers know best,” I don’t recall anyone like that among the many editors I’ve known.

“I am not taking to task the artists who combine attention-getting graphics with conveyance of substantive content. A good graphic provides emotional readiness for the words that follow.” Thank you! But?

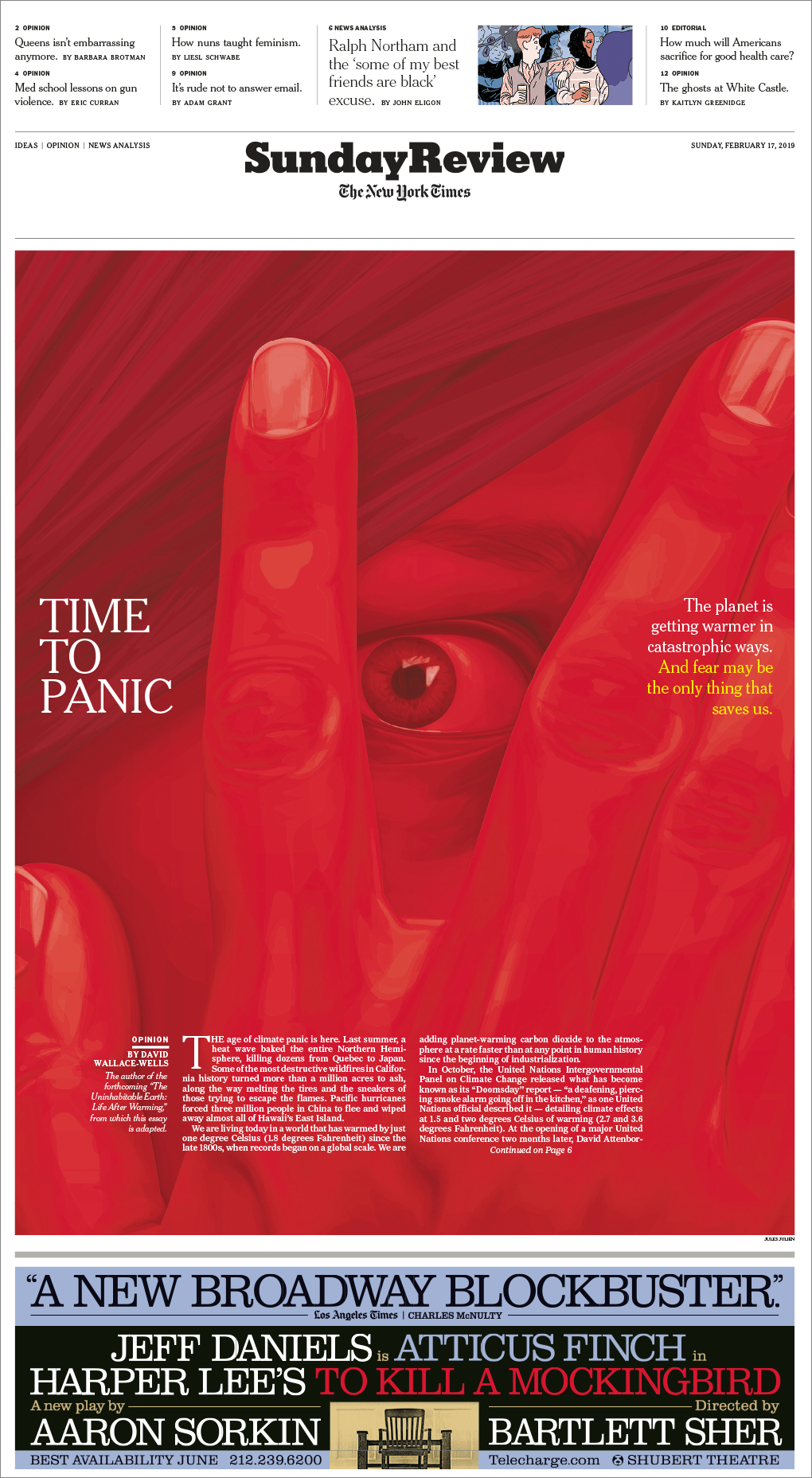

“However, in the February 17, 2019 Sunday edition of the New York Times, the page one article of the Sunday Review Section was titled, 'Time to Panic,' about global climate disruption by David Wallace-Wells. . . . The editors wanted to strike fear in readers to jolt their attentiveness to such peril, through a lurid two giant fingers with a human eye in between. A dubious attempt. Taking up the entire first page of the precious Sunday Review section (except for a hefty slice of an ad for the Broadway play 'To Kill a Mockingbird'), smattered by three paragraphs of small, white and almost unreadable text on a dark pink background, is counterproductive. Less graphic license and clearer type would have had art following function.” Sorry, Mr. Nader, that was not “graphic license”, rather eye catching graphic design that, in fact, captured the audience’s attention to read the story. Would another article have added more value to the readers? The art helped the function—and the function was to convey the story.

“Many graphic artists seem to have lost their sense of proportion—unless that is, the editors are pushing them to bleed out more and more valuable space with their increasingly extravagant designs,” continues Nader’s rant, ignoring the actual issues that drive news hierarchy. The Sunday Review is not a breaking-news section but a weekly review of critique, a magazine of sorts that “plays” a lead story based on its relative importance. Headline, photograph or illustration are the tools used to signal that importance. “It is bad enough that print publications have been shrinking due to diminished ad revenue. It is time for better editorial judgment and artistic restraint.” Perhaps “artistic restraint” is good slogan but it is bad practice.

“Unfortunately, there is no sign of such prudence. In that same Sunday edition of the Times, over eighty percent of page one of the Business Section was devoted entirely to a graphic of a presumed taxpayer smothered by flying sheets of the federal tax return—it rendered the page devoid of content.” This illustration enhanced the story and triggered interest. “At the bottom of this front page, there was a listing of five articles under the title ‘Your Taxes 2019.’ I can only imagine Times reporters gnashing their teeth about having their prose jettisoned from being featured on this valuable page of the Business Section.” What Mr. Nader calls “jettisoned” is a misstatement. Instead front page referrals (or “refers”), often result in more readers drawn into a section and tease even more stories. “That wasn’t all. The artists ran amok on the inside pages with their pointless artistry taking up over half of the next three pages of this section,” he adds, presuming that articles on other pressing business topics never reached the readers. “Gretchen Morgenson’s prize-winning weekly column exposing corporate wrongdoing used to be on page one of the Business Section. She is now at the Wall Street Journal.” A pitty for the Times but it is not the fault of the graphics.

“This is happening in, arguably, the most serious newspaper in America—one that tries to adjust its print editions to an Internet age that, it believes, threatens the very existence of print’s superiority for conversation, impact and longevity for readers, scholars, and posterity alike,” Nader claims and yet he has not come close to proving that the current Times is destroying print through its design. In fact, the contrary is true, new readers are coming to the paper version.

“I first came across run-a-muck graphic design at the turn of the century in Wired Magazine,” he adds turning his myopic eye to a pivotal magazine that was deliberately designed to be edgy and test the limits of print design and typography in the digital world. “Technology has dramatically reduced the cost of multi-colored printing. I could scarcely believe the unreadability and the hop-scotch snippets presented in obscure colors, and small print nestled in-degrading visuals. At the time, I just shrugged it off and did not renew my subscription due to invincible unreadability.” Wired was the first mass publication of the wired generation; Mr. Nader fails to recognize that it was expected to push boundaries of design in this early digital stage.

“Now, however, the imperialism of graphic designers knows few boundaries. Many graphic designers don’t like to explain themselves or be questioned by readers. After all, to them readers have little understanding of the nuances of the visual arts and, besides, maybe they should see their optometrists,” he crows. Although the “imperialism of graphic designers” has a clever sarcastic ring, it is, in fact, meaningless.

The last three paragraphs, however, proves Mr. Nader has really gone off the rails since his folly of 2000: “Well, nearly a year ago, I wrote to Dr. Keith Carter, president of the American Academy of Ophthalmology and Dr. Christopher J. Quinn, president of the American Optometric Association, asking for their reactions (enclosing some examples of designer excess). I urged them to issue a public report suggesting guidelines with pertinent illustrations. After all, they are professionals who should be looking out for their clients’ visual comfort. Who would know more?”

“Dr. Carter responded, sympathizing with my observations but throwing up his hands in modest despair about not being able to do anything about the plight of readers. I never heard from anybody at the Optometric Association.”

“Of all the preventable conditions coursing across this tormented Earth, this is one we should be able to remedy. It is time to restore some level of visual sanity. Don’t editors think print readers are an endangered species? One would think!”

Well, Mr. Nader, if you had critiqued graphic designers for illegibility crimes in the early 90s, when digital typography was in its grunge and experimental phases, you might have had a reason for a modicum of outrage. But today it seems from this post that your once acute vision is sadly impaired.