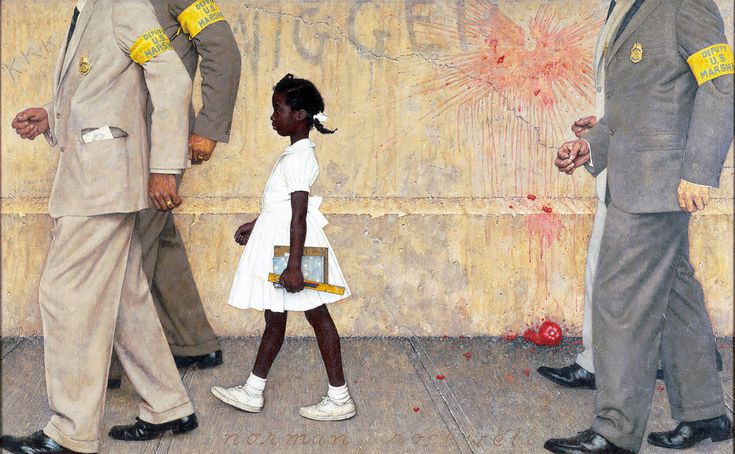

"The Problem We All Live With", Norman Rockwell

Never in his wildest dreams — and he had many throughout his life — did Norman Percevel Rockwell imagine that he would become one of America’s controversial artists. Sure, he dreamed of being popular, respected and accepted into New York society yet mostly he compulsively worked hard to be as exceptional an illustrator as those he admired, including Howard Pyle, Frederic Remington and others of the late 19th Century “Golden Age of Illustration.” These (mostly) male artists defined the styles and content of American “commercial,” “applied” and “popular” art. Rockwell saw his role as illustrator was to illuminate and entertain — to capture in paint what an author wrote in words. As The Saturday Evening Post’s most prolific cover artist for over 40 years, his aim was to paint a mythic spirit of America, not kick dust in the viewer’s eye. Being controversial — politically or otherwise — was never ever considered.

The name Norman Rockwell was as American as apple pie; his paintings were elegant, elegiac and rousing tableau that could be enjoyed by the masses. His good natured Post covers were as integral to America’s self-image as the stars and stripes and national anthem.

Rockwell was (and remains) synonymous with rock ribbed patriotic American values; his collected work was an archetype of what NYU professor Richard Halpern calls an “American innocence,” which, in turn, was also what served to get him crowned “the king of kitsch” according to art critic Clement Greenberg. Taken at face value — and given the expression-filled faces of the many American types that he employed as models to populate his populist canvases — Rockwell could be considered the most effective propagandist for the American way, perhaps ever. But there was controversy in some paintings, if not on the surface, then below the glaze.

In the late 20s and 30s as his star was rising Rockwell was not entirely set free from the chains of the mob. Just as he created his American types, he too was stereotyped as a prisoner of his own success and he had to be somewhat circumspect about what and how he painted. When he rendered a school teacher in presumably harsh light he had to endure the acrimonious letters from many school teachers. His public did not want him to veer from their proscriptions.

On a few other occasions, having been criticized for not being “modern” he attempted to work a modern touch into his art. He failed. What the public saw was to a large extent what and who he was. Throughout the early to mid-twentieth century, Rockwell was the paradigm of American commercial art, if not also a counterpoint for some. By the 60s Illustration had moved away from the tradition of painting with models but most significant was a wave of “conceptual” illustrators who, as one of the best, Robert Weaver, described as illustrating interior ideas rather than the exterior vignettes. Illustration was becoming more surreal, impressionistic and symbolic. By the early 1960s a new generation supplanted Rockwell and his cliched imitators.

In 1964, however, a year after he ended his contact with venerable and prosaic The Saturday Evening Post (because Rockwell, in fact, wanted to do work with more political gravitas) he published a major work of the Civil Rights era, The Problem We All Live With, as a centerfold in the January 14, 1964 issue of Look. The magazine offered him a place for his growing social concerns, including civil rights and racial integration. Rockwell went against type and placed black Americans as sole protagonists, instead of as observers, part of group scenes, or in servile roles. he produced a memorable document of the Civil Rights era of 10-year-old Ruby Nell Bridges, the first African-American child to desegregate the all-white William Frantz Elementary School in Louisiana, shown protected by four U.S. Marshal escorts (who were only seen from the shoulders down).

Despite an abiding faith in America’s values (as evidenced by his illustration of President Franklin Roosevelt’s “Four Freedoms”) he was not blind to the nation’s flaws. Rather than a propagandist he was a visual commentator; rather than subservience to a client — be it a product or magazine — he was true to his conscience. He made hundreds of heartfelt portraits of America but The Problem We All Live With is arguably his most socially vital work and is so resonant still.