Every absolute ruler, monarch, prime minister or president is entitled to an official portrait. It’s a perk. Designed to capture authority, ubiquity, and divinity — yet like the Wizard of Oz, there is flesh and blood behind the curtain. Sanctioned images usually reinforce the leader’s omnipotence by obscuring any blemishes or flaws. When was the last time (or the first) that you saw an official portrait of a leader with sweat on his or her brow or a five o’clock shadow or wearing glasses. Leaders hate wearing glasses (even Warby Parker frames). Queens look regal (not feminine), kings triumphant (not crazed from inbreeding), dictators strong (well, admittedly, Lenin looked rumpled), and Presidents often look like CEOs.

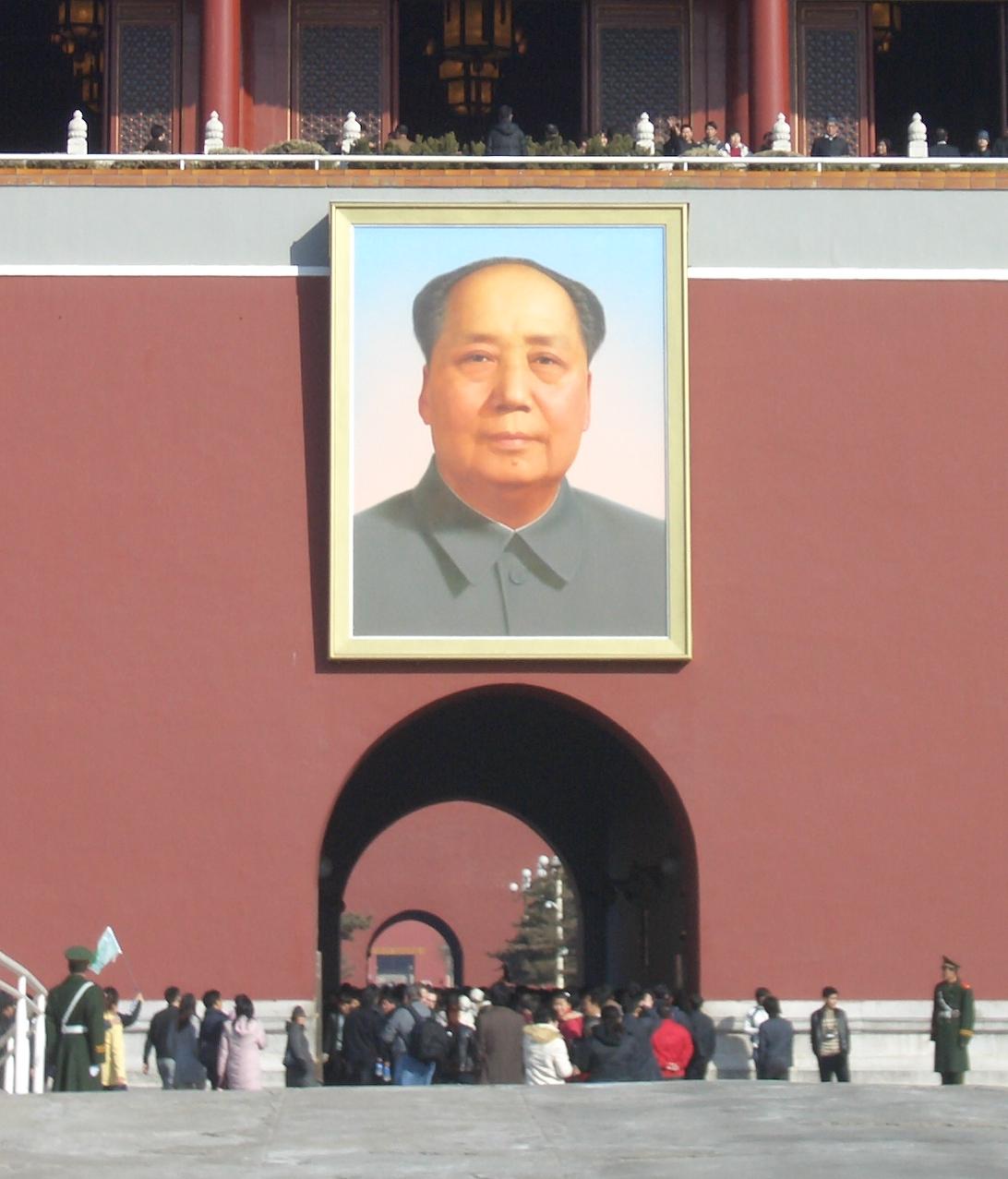

Official portraitists are never selected from the best of the best. They usually subsume their talents to the will of their subjects — and they have to be completely true to the subject’s will (which means as stiff as possible). Last week one of the little known masters of official portraiture died at 88 years old. Wang Guodong was the Chinese artist responsible for the enormous portrait of Mao Zedong that looks over Tiananmen Square in Beijing in the way that Coca Cola sign lights up Times Square (or the Camel man did decades ago).

Image by Poco a poco

Mr. Wang was chosen in 1964, when he was in his early 30s, to paint the massive Mao, the 15-by-20-foot, three stories high, metric ton oil portrait that hangs steps from the party’s central headquarters, at the Gate of Heavenly Peace. Portraits of Mao have appeared there since 1949, when the Communists took power in China. Since they are exposed to the elements, swapping them for fresher versions is routine — so, each year Wang Guodong repainted the exact same image (e.g. a painter’s “Groundhog Day”).

Mr. Wang stepped down as official portraitist in 1976, yet his assistants continued to paint Mao as Mr. Wang designed him, showing the unsmiling Mao with his trademark chin mole. Other artists in other media — posters and textiles — gave Mao a bright smile but since his teeth were black from neglect, some dental liberties were taken.

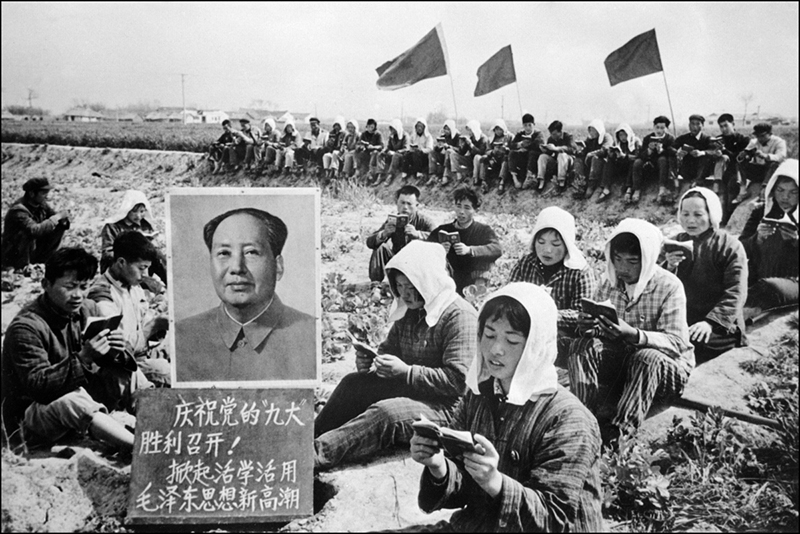

Wang is little known. Nobody is allowed to put their names on that painting. It is work for hire. And an honor. Anonymity was a duty. Unfortunately, Wang was not always honored. During the Cultural Revolution, from 1966 to 1976, Mao’s image was prominently displayed by the millions and, as was the wont of the fanatical Red Guards, Wang came under attack by the student militants who persecuted anyone they considered ideologically impure or insufficiently devoted to Mao. Maybe it was the mole. In fact, his art directorial persecution was for painting Mao from an angle with only one visible ear. He was accused of implying that Mao only listened to a few people and not the general public. Wang argued that the painting was based on a photo issued by the government from which he was not allowed to deviate, he was still publicly humiliated by the Red Guard. He was rehabilitated, however, and Mao’s ear was reinstated and listens to the people to this day.