If you love print magazines and bemoan their demise, you should be celebrating because this year substantial books on magazine design are bountiful. (Well, four is bountiful in my book.) They cover some historically important magazines — New York, Time, Holiday, Harpers’ Bazaar, Interview and their respective designers, art directors and creative directors. So, if you’re looking for seasonal gift suggestions read on.

MAG MEN by Walter Bernard and Milton Glaser, with a foreword by Gloria Steinem, is a career defining review of the mags worked on by Bernard and Glaser as WBMG (and individually too). Together they were responsible for many original and redesigns and the book’s title is more than a clever pun on MAD MEN but an apt description. Glaser co-founded New York Magazine and served as its creative director (I believe it was the first time the title was used in an editorial context) with Bernard as art director — and this was just the beginning.

When New York premiered in 1968 there was nothing called a “city magazine.” The New Yorker, despite its name, local listings, important literature, and cosmopolitan savoir faire, was in a genre all its own. It was also getting a bit musty, on its way to losing its older core audience, and headed for obsolescence (although always in my home). New York was a generational alternative. It began as the newsprint magazine supplement of the Herald Tribune (which folded in 1966). In its reincarnated form two years later under editor Clay Felker and Glaser, New York appealed to a younger generation of mid- to upper middle class New Yorkers. It had the irreverence of Esquire (which at that time included satirically and socially provocative covers by George Lois) and it ran an assortment of arts and culture listings like the Village Voice, but with more charm. Coated paper and four-color printing gave a boost to the conceptual photography, witty illustrations and clean slab-serif (Egyptian) typography, it was by far the go-to magazine for baby-boomers and baby-bloomers.

New York magazine was thoroughly documented last year in the hefty High Brow, Low Brow, Brilliant Despicable 50 Years of New York (Simon & Shuster); the section in MAG MEN on New York steers a course only through 1968 to 1976, the timeframe that Bernard and Glaser were at the helm (it is about a quarter of the MAG MEN’s overall content, through the lens of design and art direction covering all their mag work to the present). The book is filled with a surfeit of memorable editorial icons from illustrations by James McMullan for the story “Tribal Nights of the New Saturday Night,” which was the basis for the movie “Saturday Night Fever” to watercolor paintings by Julian Allen for “The Illustrated History of Watergate,” documenting in his signature photographic realism the infamous events of the Watergate scandal. In fact, the book is awash in great art by Harvey Dinnerstein, Paul Davis, Barbara Nessim, and Chwast and Glaser.

In addition to short essays and anecdotes about the staff and principals, the book is peppered with factoids and quotes from contributors, designers, photographers, and editors; sidebars about the times during which the magazine was so influential, and profiles devoted to some of the featured illustrators, including Robert Weaver, Julian Allen, Robert Grossman, and David Levine, who helped establish the magazine's graphic personality. It is sad, however, that many of these talented men and women are gone.

There are many other magazines, some better known than others, recalled in other sections of the book. After leaving New York, Bernard famously moved on to redesign and design direct Time magazine in 1977 and earned major plaudits for his efforts. He took the rather lackluster existing layout and — voila — with a few typeface changes, subheads and call-outs, illustration, and info-graphic improvements (he brought Nigel Holmes from England to be info-graphics editor who established a style later copied by many other publications), the result was a paradigm of newsweekly innovation. Bernard also gave a new gloss to the venerable Atlantic with the help of art director Judy Garlan, and he oversaw Fortune magazine’s revitalization with Margery Peters, Carol March, and Paul Richer — all names I envied for working so closely with Bernard.

In 1982, Bernard and Glaser teamed up to revamp The Washington Post and Lire (the French literary magazine) which resulted in forming WBMG. The radio-sounding initials took the mag world by storm with ESPN, The Nation, Modern Maturity, and others following suit. I could continue listing but better for you to read the book first-hand. For me, it was also a treat to recall the people I had known and respected throughout those golden magazine years, some of whom I’d forgotten. Welcome back to my consciousness and thanks for the memories.

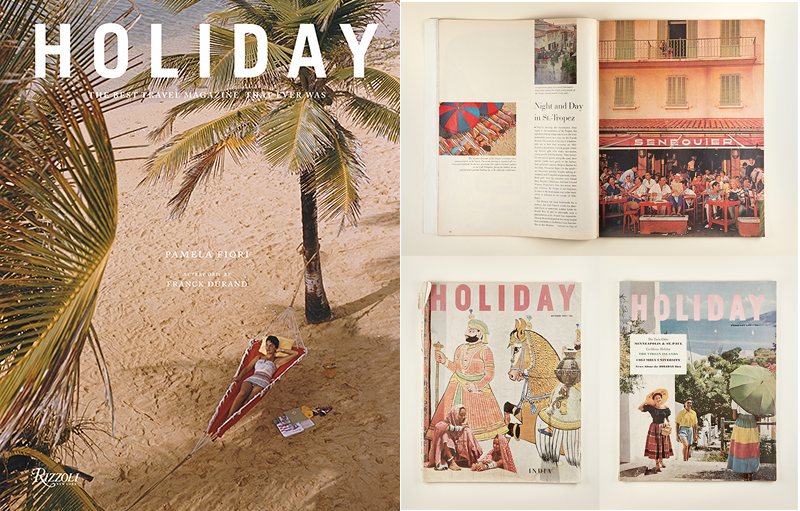

I was very excited to learn last year that former Town and Country magazine editor Pamela Fiori was writing a book on Holiday magazine, my all-time favorite since I was ten or so. She had worked at Holiday as a research assistant, fact checker, and editor during the period when Frank Zachary was art director (before moving on to edit Town and Country). I’ve written many times about Zachary, and Fiori quoted me in her wonderful book. And while that may make my judgement seem a little biased, this oversized book is honestly worth owning.

Holiday was an inspirational journey through the world of both travel and magazine art direction. Its photography, illustration, and alluring covers made me aware that magazines constituted a creative profession. We’ve all had these wake-up moments. It was in the late fifties and early sixties when I was introduced through Holiday to Ronald Searle, Milton Glaser, Seymour Chwast, and Andre François illustrations and saw there was a connection for me in their work. The names of the photographers did not register then, but their respective photo essays and images (especially Arnold Newman’s famous shot of Robert Moses standing on a bright red girder hovering over the East River) were smashing and memorable.

Fiori has captured the magazine in all its glory through reproductions (with dimensional drop shadows) of open spreads and lots of covers, She’s sprinkled Holiday: The Best Travel Magazine that Ever Was with profiles of many of the great contributors like Slim Aarons and Arnold Newman, and provides a heartfelt and informative introduction. The reproduced spreads are readable, so now I know what I was missing when I simply flipped (or rather stared intently) at the editorial spreads (I wasn’t much of a reader then). It also is a reminder that those were the days before advertising interrupted editorial wells. I could actually enjoy the stories without being frustrated by the “commercials” (what a concept).

Even if Holiday did not mean as much to you as to me, this book will make you appreciate the joys of magazine publishing. On the day each month that Holiday came in the mail it was, well, a holy day.

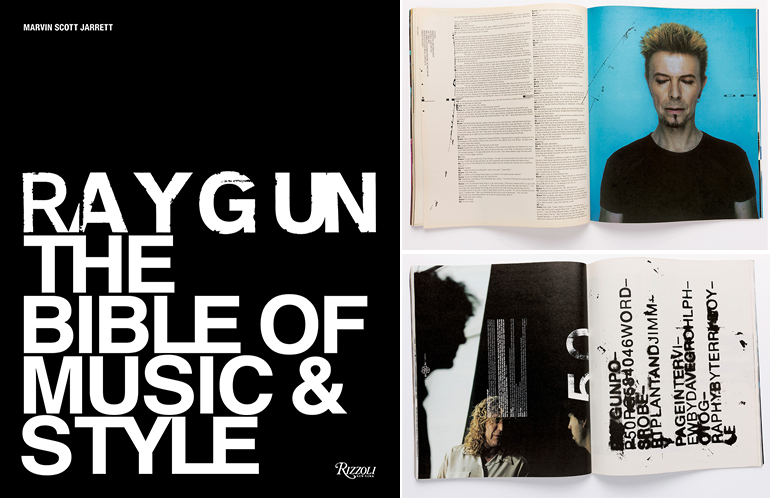

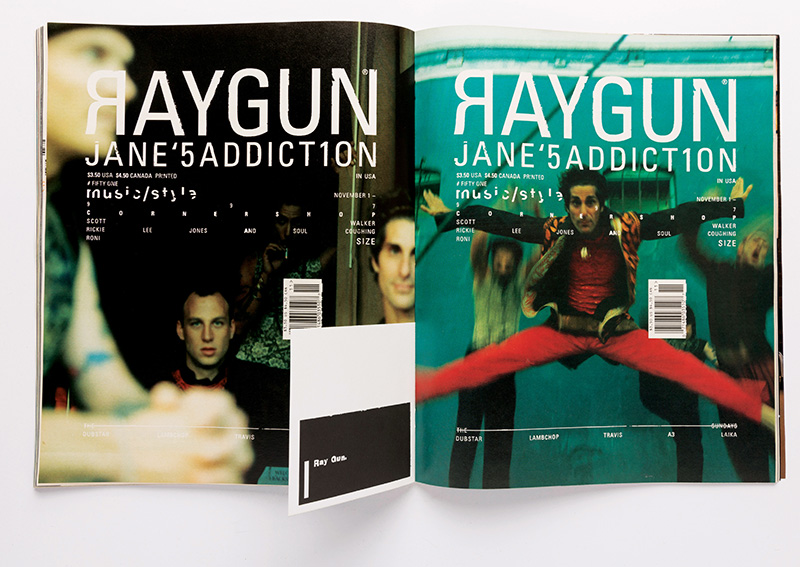

Over the past fifty years, Rolling Stone has had its share of documentary volumes. This year it was time to reprise another important (1992-2000) music mag: Ray Gun: The Bible of Music and Style (Rizzoli). I was asked to join Marvin Scott Jarrett, Liz Phair, Wayne Coyne, and Dean Kuipers in contributing an essay addressing the design. Visually defined by David Carson, Ray Gun was a monument to an era of sight and sound — and digital typography (what Neville Brody called “the end of print”). In my essay I wrote:

In the early 1990s, it was the harbinger of an unprecedented typographic style-cum-language that challenged the status quo by engaging the computer on its own terms and treating it as an art form. The magazine was arguably as media-altering as the introduction of radio and television in their day, which print also survived.

But Carson was a “disruptor.” He transgressed against the minimalist credo of mid-century modernism that was born in the Bauhaus and imported through Switzerland to corporate America; and he challenged the geometric precision of the Macintosh and those clean, expressionless layouts promised in that 1984 Apple advertisement. Rather than follow a grid or template, Carson, who bragged about being self-educated in design and the new tools, employed many of the computer’s early defaults to accomplish counterintuitive results that might best be considered anti-design. The RAYGUN designers who followed after Carson, including Robert Hales and especially Chris Ashworth, only widened the schism, if anything, and proved a significant break had occurred within graphic design.

If you lived through the Ray Gun era, this book will stoke the fires. If not, it is vivid retrospective of another wave, when art, culture, music and design were fused between front and back covers in ways that made history.

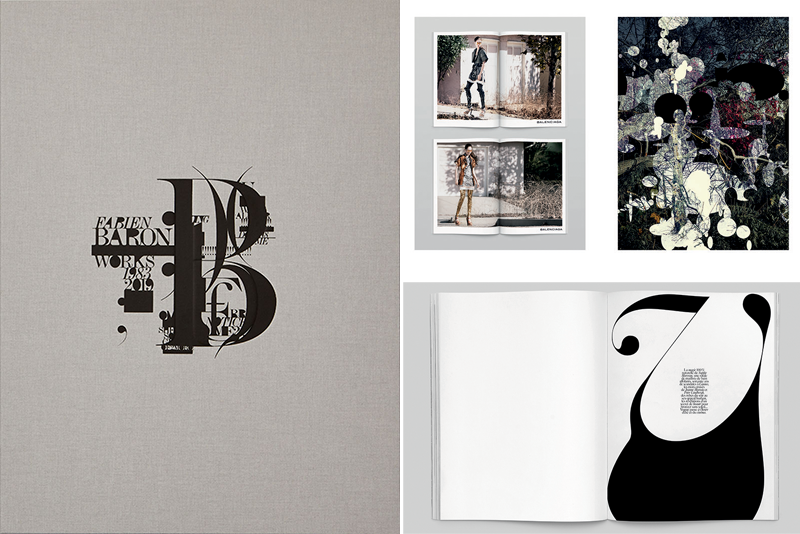

It was impossible to live through the early 1990s and early 2000s without being aware of French-born Fabien Baron’s typographic and photographic stylistic vision — that is, unless you had little or no interest in fashion, celebrity, luxury, or sensuality. The art director for Barney’s, he was hired as creative director for Italian Vogue in 1988 and in 1992 took over a similar position at Harpers Bazzar. He immediately revamped the magazine in a clean, clear, elegant, modern look that reminded one of the days when Alexey Brodovitch was art director. Baron’s iteration was singled out as the world's most beautiful fashion magazine. The same year he designed the outré, metal covered Madonna Sex book, photographed by Steven Meisel. Baron also directed a documentary with Madonna to coincide with album “Erotica,” and went on to become the doyen of superior graphic design elegance — earning a 1993 feature (“Bing! Its Fabien!”) in The New Yorker that extolled his talents (and love of Didot). In the 2000s he revamped French Vogue and Interview magazines. His reputation for risk-taking and taboo-busting increased, his typographic ingenuity expanded and his studio Baron + Baron became the go-to for class and lux.

Now his own monograph, Fabien Baron Works: 1983-2019 (Phaidon), a huge block, weighing in at 11.3 lbs and 11.8 x 2 x 15.3 inches, with essays by Kate Moss and Adam Moss, monumentalizes his contribution to magazine history (however, causing this reader to have a strained back from attempting to pick it up). Baron is a multi-talented force in the worlds of fashion editorial and advertising — from layout to art direction, from photographer to film and video director. And the book supports this assertion. But there is also something out-of-proportion too. While there is a trend in producing large, heavy, cinemascope-ish volumes that sell for over $100, it is excessive. Most of the images approximate life size reproductions but rather than a document of significant work it is at times an indulgent ostentation, like a book equivalent of the Arc de Triomph. Okay, Baron deserves the reverence, yet a few pounds and couple of inches cut from the overall package wouldn’t have hurt as much as this reader’s strained muscles and would have been more accessible too. That said, given Baron’s reputation as the most sought after creative director in the world, we could not expect less.

For the magazine-lover these books cannot help but kindle and rekindle (no, not the digital reader) the feelings for great magazines that many of us still hold close to the heart.