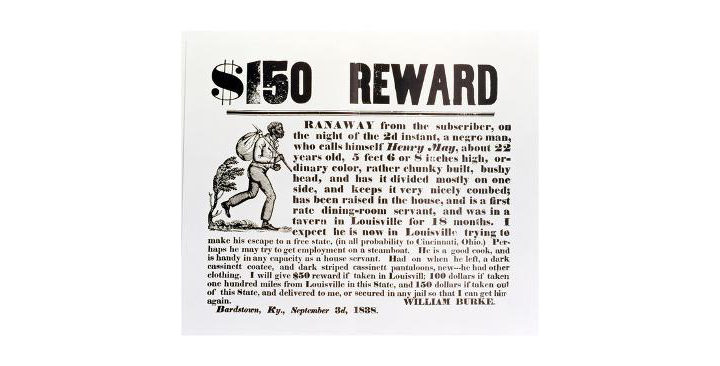

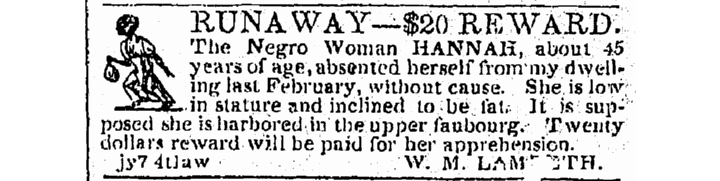

In almost every American type foundry specimen catalog published during the antebellum period, printers and typesetters were offered a selection labeled “Ornaments” that included generic wood cuts and metal engravings of every conceivable description that were used to illustrate advertisements. These functional little spots or “cuts” were mostly innocuous pictures of sundries, consumables, professional signs, and symbols, but one motif was not at all benign.

The image of a black man and/or woman either walking or sitting did not demonize per se, but the runaway slave it represented was packed with powerful symbolism masking a horrid system. Owing to the small printing size of the image, unless you looked closely at the walking man (shown here) carrying a bag of belongings on a stick over his shoulder, akin to the classic caricature of a wandering hobo, it would not have any horrific significance. Yet in the decade leading up to the Civil War, the variations of this picture that multiplied in numerous newspaper advertisements had monstrous implications and ramifications; this was the standard personification or brand of the “Runaway Slave” and the advertisements it adorned was calling on citizens, law enforcement, and bounty hunters to capture a piece of property to be returned to its rightful owner.

As Andrew Delbanco writes in his excellent The War Before The War: Fugitive Slaves and the Struggle for America’s Soul from the Revolution to the Civil War (Penguin Press): “In 1841, when Charles Dickens came to the United States on a bookselling tour, he was struck by the many newspaper notices . . . in which slave owners offered rewards for return of their runaways.” In fact, these ads, and this charged, ubiquitous image, was aimed at Northerners not Southerners, a reminder that the United States was fragilely held together by a law called “The Fugitive Slave Act.”

This law, which relied on extrajudicial enforcement for many years and both federal and interstate cooperation for many others, was created to balance the distinction between the Northern “free-soil” from the Southern slave-holding states, and especially to limit the ability of anti-slavery abolitionists and non-slave state governments to prevent the return of escapees. Although some slaves located on the boarder states were able to flee to freedom in the North (including Canada, which as a dominion of England prohibited slavery), many untold numbers of those in the slave population were caught and returned (and even freemen were kidnapped and sold into slavery). Those in the lower South had practically no chance to make the dangerous journey up north.

The percentage of successful runaways was comparatively low. But the advertisements placed in Northern newspapers (many of which accepted them without hesitation, despite editorial support of abolition) gave the impression of many — and Delbanco notes that perhaps there were more than any census could attest.

Unspeakable tortures were meted out to recaptured runaways (as well as to those who did not runaway), but the printers’ images gave no hint of the terror. The calm of the image hides a grotesque reality (the easy-going gait of the man who is dressed not in rags but with shoes and blouse, with a windblown sapling behind him implies no pain). In truth, when he or she is found everything from punitive branding to severe whipping and worse physical depredation greeted the slave. Could it be that the artists that made the cuts and editors that placed them in the newspaper had no idea how complicit they were? Or were they simply responsibly obeying the law of the land enacted to prevent disunion through collaboration with the slave owners? The tone of the image says one thing and the truth of slavery was another more unspeakable thing.